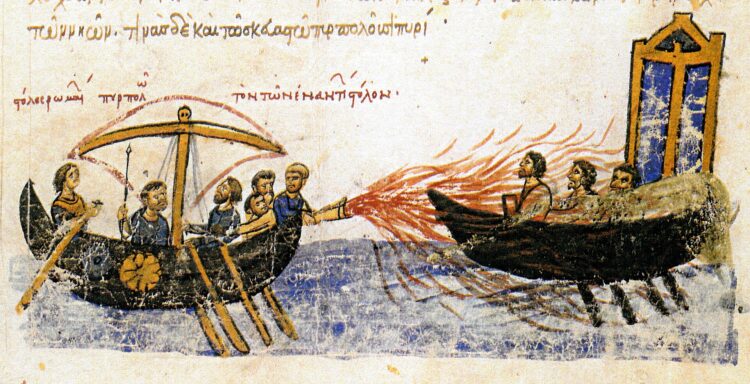

Hand grenades have been an integral part of warfare for centuries, evolving from primitive incendiary devices to sophisticated explosives. These small yet powerful weapons have played a crucial role in military tactics, shaping the course of battles throughout history. The earliest recorded grenades date back to the 8th century CE, originating from the Byzantine Empire. Known as “Greek Fire,” these incendiary weapons were used to set enemy ships ablaze. The secrets of Greek Fire were closely guarded, and its composition remains shrouded in mystery. Nevertheless, what is known about this ancient weapon paints a vivid picture of its devastating power and the fear it instilled in enemies. Unlike other incendiary substances of the time, Greek Fire could burn even on water, making it a formidable weapon against enemy ships. It adhered to targets and continued to burn fiercely, creating a terrifying spectacle for those unfortunate enough to face it.

The Greeks began to fling their fire all around; and the Rusii seeing the flames threw themselves in haste from their ships, preferring to be drowned in the water rather than burned alive in the fire (Liutprand of Cremona, Antapodosis, describing a Byzantine battle in 941 CE)

Early accounts suggest that it was initially launched using tubes or siphons from ships. These siphons could project the substance in a pressurized stream, engulfing enemy vessels in flames. Other accounts mention the use of ceramic pots or grenades filled with Greek Fire, which were hurled at enemy ships, causing widespread panic and destruction.

Over time, the concept spread to the Islamic world and the Far East, where Chinese grenades with metal casings and gunpowder fillings emerged. These early grenades relied on simple mechanisms such as waxed candlestick fuses. The origins of Chinese hand grenades can be traced back to ancient times, where they were initially developed during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). These early grenades featured a metal casing, usually made of iron or bronze, which contained a gunpowder filling. The gunpowder was ignited by a fuse mechanism, which often consisted of waxed candle sticks. Ancient Chinese hand grenades were primarily employed in warfare as a means to disrupt and disorient enemy forces. They were particularly effective against densely packed infantry formations, fortifications, or during sieges.

Hand grenades gained widespread military use in Europe during the 16th century. The first European grenades were hollow iron balls filled with gunpowder, ignited by a slow-burning fuse rolled in dampened gunpowder. These early designs weighed between 2.5 and six pounds each. During the Napoleonic Wars, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte recognized the value of grenadiers and incorporated them into his formidable armies. Grenadier units were recruited from various regiments, often comprising the most experienced and battle-hardened soldiers. These units represented the pinnacle of military training and discipline, serving as the shock troops and guardians of Napoleon’s strategic maneuvers.

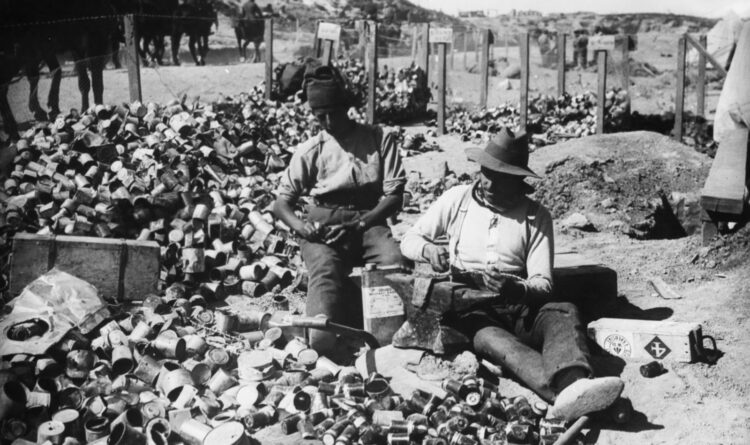

As firearms improved during the 19th century, the popularity of hand grenades diminished, and they fell out of widespread use. However, their resurgence occurred during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), where they played a significant role. The grenades used during World War I were improvised and often consisted of tin cans filled with gunpowder and stones, with primitive fuses. The Australians even repurposed jam cans, earning their grenades the nickname “Jam Bombs.” The soldiers would collect empty tin cans, usually jam cans, and repurpose them into makeshift explosive devices. The process involved filling the cans with gunpowder or other explosive materials and adding stones or shrapnel to enhance their fragmentation capabilities. A primitive fuse, often made from a matchstick or other available materials, was inserted into the grenade for ignition. While jam bombs were not as sophisticated or standardized as the manufactured hand grenades of the time, they served as a resourceful solution for Australian soldiers who often had limited access to official military supplies.

A pivotal moment in the history of hand grenades came with the invention of the Mills bomb in 1915 by British engineer William Mills. This groundbreaking design incorporated elements from a Belgian self-igniting grenade while introducing safety enhancements and improved efficiency. The Mills bomb revolutionized trench warfare during World War I, becoming an iconic weapon. Millions of Mills bombs were manufactured by Britain, solidifying their place in history.

Two notable hand grenade designs emerged during World War I. The German stick grenade, or Model 24 Stielhandgranate, featured a wooden handle with a metal head containing the explosive and fragmentation materials. Though effective, it had design flaws and the potential for accidental detonation. On the other hand, the Mk II “pineapple” grenade, developed for the U.S. military in 1918, had a segmented metal body resembling a pineapple. Known for its fragmentation capabilities, the Mk II became a symbol of American military might.

Hand grenades continue to be vital assets in modern warfare, with various types and designs tailored for specific objectives. Fragmentation grenades, concussion grenades, and smoke grenades are among the commonly used types today. Modern grenades incorporate advanced safety features, reliable fuses, and materials for maximum effectiveness on the battlefield.

Source

https://www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Fire/

https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/chinese-invention-gunpowder-explosives-and-artillery-and-their-impact-european-warfare

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/ww1/military-organisation/army-weapons