Remains of the Alamut Castle in Qazvin, Iran. Photo by Alireza Javaheri / CC BY 3.0 Copped/DEED. Cropped.

The Hashshashin, also known as the Assassins, were a religious sect of Ismaili Shi’a Muslims from the Nizari lineage. They originated in Persia during the 11th century. This secret society was known to specialize in terrorizing the Crusaders, against whom they fearlessly executed political assassinations. Their tactics and operations had a significant impact on the political dynamics of the Middle East during that era.

The term “Hashshashin” or “Assassin” is believed to have originated from the Arabic word “hashshashin,” which means “users of hashish”. However, this etymology may have arisen after the name itself, as a creative attempt to explain its origins.

Early History

The Assassins’ library was destroyed when their fortress fell in 1256, so we do not have any original sources on their history from their own perspective. However, we know that the Assassins were a branch of the Ismaili sect of Shia Islam.

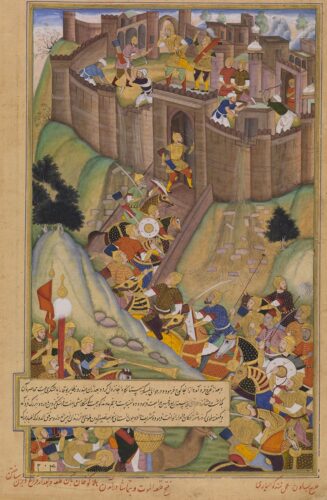

The founder of the Assassins was a Nizari Ismaili missionary called Hasan-i Sabbah, who infiltrated the castle at Alamut with his followers and bloodlessly ousted the resident king of Daylam in 1090. From this mountaintop fortress, Sabbah and his faithful followers established a network of strongholds and challenged the ruling Seljuk Turks, Sunni Muslims who controlled Persia at the time.

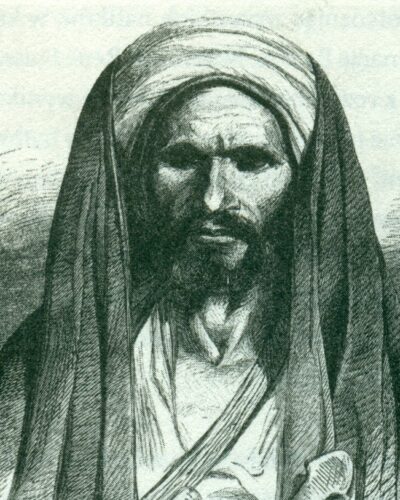

Hasan-i Sabbah

Hasan-i Sabbah was born around 1050 in Qom, which was part of the Seljuk Empire (present-day Qom, Iran). He studied theology in the Iranian city of Rayy. At about the age of 17, he adopted the Ismāʿīlī faith. In 1076, Sabbah traveled to Egypt, likely for further religious training. He stayed there for approximately three years.

Upon his return to Iran, Sabbah traveled extensively to promote Ismāʿīlī interests. He made numerous converts and, in 1090, with the help of converts within its garrison, he seized the great fortress of Alamūt in Daylam, a province of the Seljuk empire.

Sabbah ruled the Nizari Ismaili state from 1090 to 1124. He led an ascetic existence and imposed a puritanical regime at Alamūt. He was known for his strict justice; when one of his sons was accused of murder and the other of drunkenness, he had them both executed.

Sabbah was not only a formidable leader but also an accomplished scholar of mathematics, most notably in geometry, as well as astronomy and philosophy, especially in epistemology. He wrote several cogent theological treatises, emphasizing the need to accept absolute authority in matters of religious faith. His expression of this doctrine became widely accepted by contemporary Nizārīs. Hasan-i Sabbah passed away on June 12, 1124. His leadership and the sect he founded left a lasting impact on the history of the Middle East.

The Assassins had several leaders after Hasan-i Sabbah. Upon his death in 1124, he was succeeded by Kiya Buzurg Ummid. The appointment of a new da’i at Alamut may have led the Seljuks to believe the Assassins were in a weakened position, and Ahmad Sanjar launched an attack on them in 1126.

The Assassins continued to be guided by successors for nearly two centuries after Sabbah’s death. However, the specific details about these leaders are not as well-documented as those of Sabbah. The Assassins were eventually dissolved in 1275. Today, they are survived by the Shia Imami Isma’ili Muslims in the contemporary world, otherwise known as the Nizari, and are currently led by the Aga Khan IV, their 49th Imam.

Comprehensive Training

The training of the Assassins was a combination of physical training, language learning, stealth tactics, religious indoctrination, and psychological manipulation. This comprehensive training made them one of the most feared groups in the Middle Ages.

The Assassins were religiously trained every single minute of every day They were mastering all kinds of techniques, martial arts, poison chemistry, espionage, infiltration. They were fluent in several languages, which was crucial for their operations in different regions and among different cultures.

The technique they excelled in the most was the art of subtlety. This involved blending into different societies, gaining the trust of their targets, and carrying out assassinations without arousing suspicion.

Marco Polo described the Assassins as men who were drugged with hashish wine and then taken to a lush valley where all of their sexual desires were fulfilled to gain their loyalty. From then on, the leader of the sect could order these men to carry out any command, even brutally killing themselves.

The Assassins were a religious group, and their training also involved religious indoctrination. They were taught the tenets of the Ismaili sect of Shia Islam, and they were prepared to die for their faith.

Infiltration and Espionage

The Assassins were known for their strategic and meticulous methods of infiltration and espionage. The Assassins were trained to blend into different societies. They would monitor both Muslim and Christian leaders in the Middle East, watching from the shadows. They would infiltrate the courts of their targets, sometimes serving for years as advisors or servants. This allowed them to gain the trust of their targets and carry out assassinations without arousing suspicion.

The Assassins were also skilled spies. They would gather information about their targets, their habits, their guards, and their routines. This information was crucial in planning their assassinations.

Interestingly, the Assassins’ relationship with Muslim and Christian leaders was complex and sometimes collaborative. They attempted to assassinate Salah al-Din, but later formed working relationships with him and King Richard.

Assassination Tactics

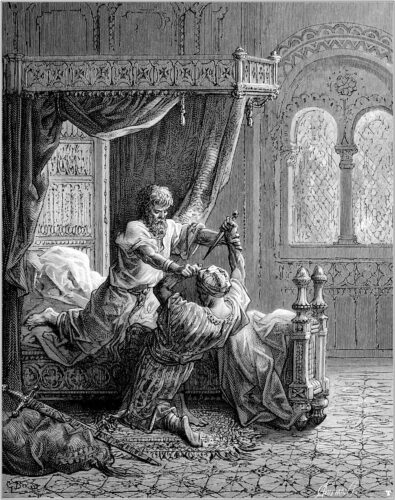

In order to get rid of anti-Nizari rulers, clerics, and officials, the Assassins would carefully study the languages and cultures of their targets. An operative would then infiltrate the court or inner circle of the intended victim, sometimes serving for years as an advisor or servant. At an opportune moment, the Assassin would stab the sultan, vizier, or mullah with a dagger in a surprise attack. Assassins were promised a place in Paradise following their martyrdom, which generally took place shortly after the attack.

A hallmark of the Assassins’ killings was that they were as public as possible so as to sow maximum fear This often resulted in the death of the Assassin, but it also served to enhance their reputation and instill fear in their enemies.

The Assassins were known to use a variety of weapons, including daggers and small blades, which were easy to conceal. These weapons were often poisoned to ensure the death of their target.

Final Thoughts

The Hashshashin were a formidable force in the Middle East during the 11th to 13th centuries. Their stealthy methods and the use of assassination as a means of achieving their objectives made them a feared group. Their legacy continues to influence modern perceptions of assassins and their tactics.