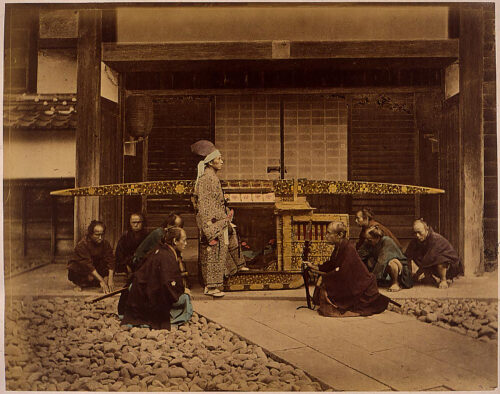

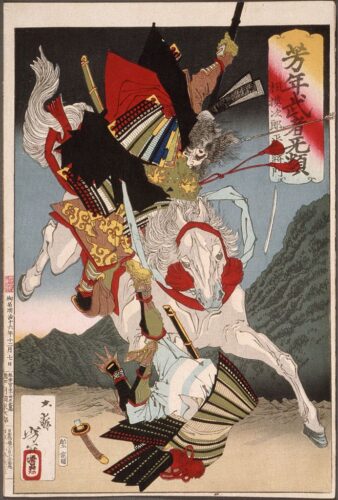

16th century illustration of samurai raiding the house of Minamoto no Yoshitsune.

The only reason a warrior is alive is to fight, and the only reason a warrior fights is to win.” ― Miyamoto Musashi, “The Book of Five Rings”.

The samurai, an elite warrior class that emerged in Japan in the 10th century, have long fascinated historians and cultural enthusiasts alike. Known for their martial prowess, strict code of ethics known as Bushido, and significant influence on Japanese culture, the Samurai represent a unique aspect of feudal Japan.

The term “samurai” was originally used to denote the aristocratic warriors (bushi). They were the well-paid retainers of the daimyo, the great feudal landholders. Samurai came to apply to all the members of the warrior class that rose to power in the 12th century and dominated the Japanese government until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.The samurai’s primary loyalty was to their daimyo and the shogun. Their relationship with the imperial court was more complex. During the periods of samurai rule, the imperial court was largely sidelined from political power.

Emerging from provincial warrior bands, the samurai of the Kamakura period (1192–1333), with their military skills and deep pride in their stoicism, developed a disciplined culture distinct from the earlier, quiet refinement of the imperial court. During the Muromachi period (1338–1573) under the growing influence of Zen Buddhism, the samurai culture produced many such uniquely Japanese arts as the tea ceremony and flower arranging that continue today.

The ideal samurai was supposed to be a stoic warrior who followed an unwritten code of conduct, later formalized as Bushidō, which held bravery, honor, and personal loyalty above life itself. Ritual suicide by disembowelment (seppuku, also called hara-kiri) was institutionalized as a respected alternative to dishonor or defeat.

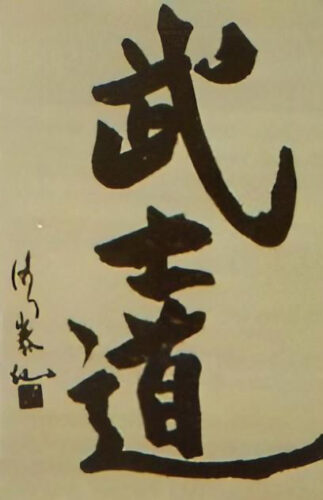

Bushidō

Bushidō, often translated as “The Way of the Warrior,” had a profound influence on the daily life and behavior of the samurai. This set of principles dictated the samurai code of life in feudal Japan. The key virtues of Bushidō —courage, honor, and loyalty—demanded that a samurai live a life dedicated to duty and the service of their lord. This often required the ultimate sacrifice. These virtues and ethics grew into an elaborate code emphasizing honor, courage, and loyalty.

Bushidō’s origins can be traced to influences including Shinto, Buddhism, Confucianism, and the existential needs of the samurai themselves. It cemented a framework for decision-making and guided the interpretation of honor and service. The samurai were not just warriors; they were also guardians of the social order and exemplars of the virtues they were meant to uphold. Bushidō’s sophisticated nature cultivated a warrior class that was both lethal in combat and refined in character.

Influenced by Confucianism and Zen Buddhism, Bushidō encompassed not only martial skills but also moral and intellectual virtues. The hierarchical social structure and the constant threat of warfare further shaped the samurai’s mindset and their commitment to honor and loyalty.

In essence, Bushidō shaped the moral compass and organizational culture within the historical domain and across contemporary Japan, imbuing aspects of discipline, honor, and loyalty into daily life. It was more than a martial discipline—it evolved into a way of life influencing societal values and personal conduct within Japanese culture.

The Book of Five Rings

The Book of Five Rings (Go Rin No Sho) is a classic treatise on strategy and martial arts, written in 1645 by Miyamoto Musashi, a renowned Japanese swordsman. The book is divided into five sections or ‘books’, each corresponding to an element in Buddhist philosophy: Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, and Void. Musashi utilizes these elements to illustrate strategic concepts, and he further explores the metaphysical aspects of warfare, martial arts, and life.

The Book of Five Rings is highly significant in the context of Bushidō. Musashi discusses the importance of broad knowledge and strategic thinking, emphasizing that the path of the warrior is one that requires constant learning, not just about martial arts, but also about the world. He introduces the concept of the “Way of the Warrior” (Bushidō) and his own style, Niten Ichi-ryū, a two-sword technique. The strategy includes understanding your opponent’s strengths and weaknesses and knowing the right time to attack or defend.

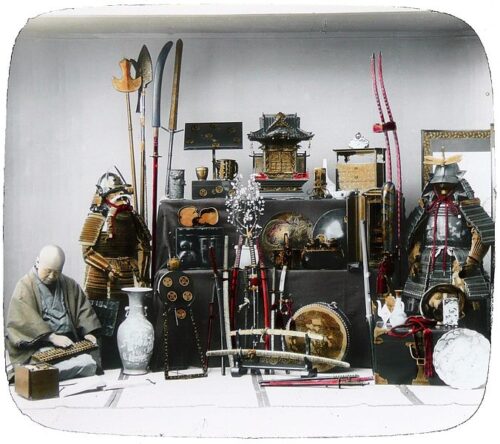

Weapons and Armor

The Samurai were known for their mastery of a variety of weapons. The katana, a curved, single-edged sword, was the primary weapon of the samurai. Its long, slightly curved blade provided an optimal balance of cutting power and speed.It was designed for slashing and thrusting, making it particularly effective in close combat,Traditionally, the katana was paired with the wakizashi, a shorter sword, to form the daisho, a symbol of a samurai’s status and honor.

The wakizashi was a vital part of the samurai’s arsenal. With a blade length of approximately 30-60 centimeters (12-24 inches), it was used for close-quarters combat, self-defense, and ceremonial purposes.

In addition to their swords, the samurai were also skilled archers. The yumi, or the Japanese longbow, was a formidable weapon in the hands of the samurai. Its asymmetrical shape allowed for more efficient use on horseback.Samurai archers trained extensively to master the art of Kyūdō, the way of the bow.

Another weapon in the samurai’s arsenal was the naginata, a pole weapon with a curved blade. This versatile and deadly weapon’s long reach allowed samurai to engage opponents at a distance, while its curved blade was effective for both slashing and thrusting. This array of weapons, each serving a unique purpose, contributed to the samurai’s effectiveness on the battlefield.

Samurai armor, known as yoroi, was a crucial element of the samurai’s equipment, providing protection and symbolizing status. The armor was made from a combination of materials, including leather, lacquered wood, and metal, and was designed to be both lightweight and flexible. The traditional suits of armor consist of the kabuto (helmet), the dou (main armor for the torso), the kusazari (armor for the legs), the kote and kogake for the arms.

The samurai’s iconic equipment and weapons played a crucial role in their effectiveness on the battlefield and in maintaining their social status. They were both functional and highly decorated, reflecting the samurai’s skill, honor, and aesthetic sensibility.

Battle Tactics

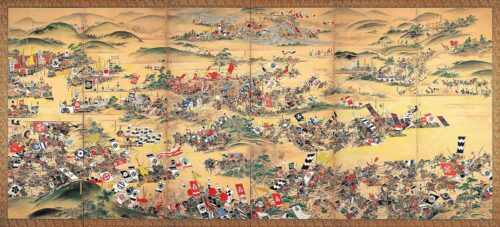

Samurai battle tactics were complex and evolved over time, adapting to changes in weaponry, technology, and the nature of warfare itself. In the early stages of the samurai era, from the 12th century and up to the late 15th century, warfare was characterized by highly mobile cavalry-archer units. Early battles were conducted predominantly on horseback. Great phalanxes and spear divisions were added into the mix over the course of the Middle Ages, with a final concentration on guns in the latter half of the 16th century.

Traditionally, when a samurai went into battle, he was there to gain honor for himself and his family name. He did this by challenging individual warriors to a fight; once his opponent was dispatched, he would move on to the next and the next until the battle was over or he himself was injured or killed. However, by the second half of the 16th century, major battles in Japan became more advanced and samurai war tactics were more complex, often involving larger numbers of troops. The army’s victory was all-important and now warriors were expected to fight how, when, and where they were told by their general.

Samurai tactics employed the use of various weapons to attack at close, short, and long range. Regardless of the image the samurai has of using only swords, they would use long-range weapons like bows and arrows to attack the enemy from long range. The samurai were also proficient in hand-to-hand combat, using ancient techniques collectively known as jujitsu. The objective of the various forms of jujitsu was to use an opponent’s strength against him by employing handholds and deft maneuvers to throw the opponent off balance.

The Role of Samurai in Society

In the early part of the Tokugawa period (1603–1867), the samurai, who accounted for less than 10 percent of the population, were made a closed caste as part of a larger effort to freeze the social order and stabilize society. Although still allowed to wear the two swords emblematic of their social position, most samurai were forced to become civil bureaucrats or take up some trade during the 250 years of peace that prevailed under the Tokugawa shogunate (military dictatorship).

Meiji Restoration

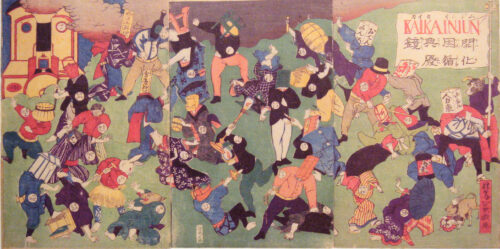

In 1868, a significant event known as the “Meiji Restoration” occurred in Japan. This marked the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the restoration of the Emperor Meiji to power. The Meiji Restoration led to rapid modernization and industrialization in Japan.

The samurai class, which had been a dominant force in Japan for centuries, underwent a dramatic transformation during this period. The Meiji Restoration and the modernization that followed resulted in the samurai losing their class privileges. In 1870, a military academy was established, and in 1876, the wearing of samurai swords was banned.

The samurai class was far from monolithic, with over one hundred classifications of rank in samurai society.The Tokugawa warlord system, which lasted for about two centuries, had progressively transformed samurai into what can be described as “civil servants”. They had already lost their status as independent warriors by the mid-nineteenth century.

The transition from a feudal society to an empire by 1868 meant that there was no place for the samurai². This period of peace and military reform was largely responsible for the disappearance of the samurai². Despite this, the legacy of the samurai and their code of conduct, known as Bushido, continues to have a significant influence on Japanese culture.

Japan Self Defense Forces

The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) emerged as the successors to the Empire of Japan’s Armed Forces, which were in operation from 1868 to 1947. The establishment of the JSDF was formalized in 1954 through the enactment of the Self-Defense Forces Act (Act No. 165 of 1954). The primary role of the JSDF is to safeguard the nation, a mandate that is shaped by the constraints of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution. The concept of Bushido, while not actively practiced, is symbolically represented, such as in the naming of military exercises like the 2019’s Exercise Bushido Guardian. The idea of incorporating Bushido into the JSDF has both proponents and critics.

Final Thoughts

The Samurai were not just warriors, but a class of people who left an indelible mark on Japanese history and culture. Their strict adherence to the code of Bushido, their mastery of martial arts, and their unwavering loyalty and honor have made them iconic figures. The Samurai’s influence extended beyond the battlefield into the realms of art, philosophy, and culture, shaping Japan’s identity in profound ways. Even today, the legacy of the Samurai continues to resonate, reminding us of a time when honor was worth more than life itself. Their story is a powerful illustration of the human spirit’s resilience and the enduring appeal of the values they embodied. The samurai remain a fascinating subject of study, offering insights into a unique aspect of Japanese history and a way of life that continues to inspire people around the world.