Alan Ladd on cover of “Modern Screen”, April 1946. Cropped.

Throughout the course of the Second World War, a significant number of Hollywood’s finest chose to serve their nation by joining the ranks of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Among these were the esteemed filmmaker and Oscar recipient, John Ford, and the renowned Disney visual effects artist, Bob Broughton. Their collaborative efforts resulted in the production of instructional films for the OSS and the documentation of OSS operations, marking the inception of the use of cinematography in intelligence work.

During this period, due to the clandestine nature of the OSS, Hollywood studios were under strict instructions to exclude any reference to the OSS in their films. Despite this, screenwriters managed to subtly incorporate elements of the OSS into their scripts without explicitly mentioning it. A number of Hollywood luminaries, including the charismatic actor and OSS veteran, Sterling Hayden, were instrumental in this effort.

Hollywood played a pivotal role in shaping public perception of the enemy during the war. A prime example of this is Walt Disney’s animated short, Der Fuehrer’s Face (December 1942), which satirically invited audiences to salute Hitler, thereby ridiculing the enemy.

However, some government officials advocated for a more nuanced portrayal of the enemy, suggesting that the focus should be on the militaristic systems of the Axis powers rather than individual figures. This strategy was aimed at highlighting the oppressive ideologies of the enemy and rallying public support for the war effort, thereby fostering a united front against the Axis powers.

Post World War II

World War II came to a close with the surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, 1945. In the same month, President Harry Truman, harboring doubts about the necessity of the OSS in a post-war government, issued Executive Order 9621, effectively dissolving the organization. Despite this, General William Donovan, the head of the OSS, was determined to ensure the legacy of the OSS lived on. He wanted the public to be aware of and remember the heroic deeds of the OSS’s men and women. To this end, Donovan urged former OSS officers to pen articles and memoirs that highlighted the organization’s remarkable missions. A number of these ex-OSS officers, who had a flair for writing, made their way to Hollywood.

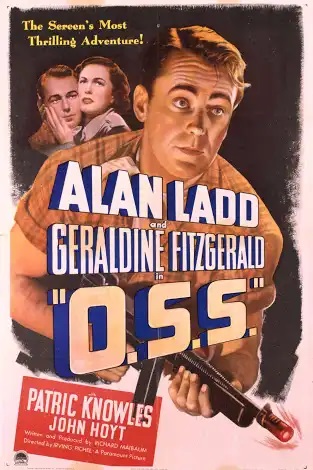

O.S.S.

O.S.S., the first film about the Office of Strategic Services, was released in theaters on May 26, 1946. Directed by Irving Pichel, the film starred Alan Ladd in the lead role. The film tells the story of John Martin, played by Ladd, who is arrested at the beginning of the film for attempted industrial espionage. Martin’s knack for breaking and entering, however, saves him from jail time. Instead, he is turned over to the newly created OSS for training. The OSS, recognizing Martin’s unique skills, sends him to France for his first assignment. The film follows Martin and his team as they navigate the dangerous world of espionage during World War II.

The screenplay was written by Richard Maibaum, a World War II veteran who would later write twelve of the first fifteen James Bond films. Maibaum, a former Broadway actor, also narrates the film.

O.S.S. was produced and distributed by Paramount Pictures and portrays the activities of the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. Despite being a work of fiction, the film provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of espionage during this era.

The film was well-received, and its success led to other Hollywood studios producing their own OSS-themed films. O.S.S. thus marked the beginning of a trend that would see the OSS and its operations become a popular subject in Hollywood cinema.

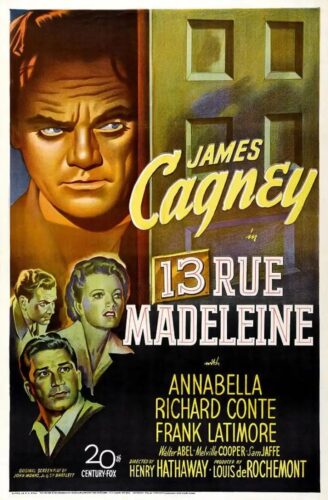

13 Rue Madeleine

One such film was 13 Rue Madeleine (1947), a spy thriller that was being developed in Hollywood around the same time as O.S.S. Released in 1947, this spy thriller was directed by Henry Hathaway and starred James Cagney, Annabella, Richard Conte, and Frank Latimore. The film’s title, 13 Rue Madeleine, refers to the address of a Gestapo headquarters in Le Havre, France. This detail added a layer of realism to the plot, grounding the film’s narrative in a tangible location within the theater of World War II.

The plot of 13 Rue Madeleine revolves around the training of Allied volunteers as spies in the lead-up to the invasion of Europe. However, one of these volunteers is revealed to be a German double agent. The film follows the efforts of the OSS to feed this agent false information about the invasion, while the real agents are sent to France to find a secret V-2 rocket depot.

13 Rue Madeleine was well-received and benefited from the postwar craze for shooting outside the studio. With Quebec doubling for occupied France, this spy movie offered audiences a sense of open air.

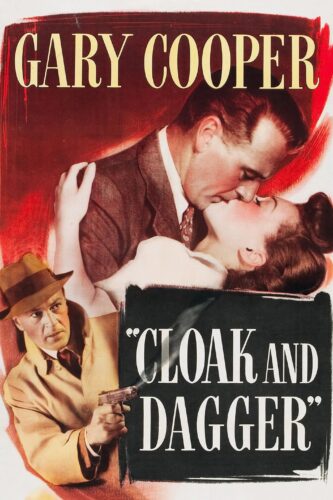

Cloak and Dagger

Another notable film was Cloak and Dagger. Released in 1946, this war drama was directed by Fritz Lang and starred Gary Cooper. The film is based on the 1946 non-fiction book Cloak and Dagger: The Secret Story of the O.S.S. by Corey Ford and Alastair MacBain.

The plot of Cloak and Dagger revolves around an American scientist, played by Gary Cooper, who is sent by the OSS to contact European scientists working on the German nuclear weapons program. Lilli Palmer stars as a member of the Italian resistance movement who shelters and guides him.

Cloak and Dagger is notable for its realistic portrayal of the OSS’s operations during World War II. The film’s narrative, grounded in the real-life experiences of OSS agents, provides audiences with a unique insight into the world of espionage during this era.

While Cloak and Dagger is based on a non-fiction book, the film itself is a work of fiction. As such, its portrayals of OSS operations and agents may not be entirely accurate. However, the film does provide a fascinating look at how Hollywood viewed and portrayed the world of espionage during this era.

Final Thoughts

The relationship between Hollywood and the OSS during World War II was a unique one. It was a time when the glamour of Hollywood and the gritty reality of war intersected, creating a fascinating chapter in both film and military history. The legacy of the OSS continues to be remembered and celebrated, thanks in part to the stories and films that emerged from this remarkable collaboration.

Resources

Central Intelligence Agency

CIA.gov

OSS Society

OSSSociety.org

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.