QUESTION FROM SOCIAL MEDIA: How does body-type affect training protocols? Some guys are more natural runners/endurance types, and some are more lifting/heavyweight types. Does this affect training, and if so how?

ANSWER: No. But it does affect performance potential. Welcome to the world of genetics!

This is one of those questions that really needs a hefty dose of elaboration.

This question refers to body type classifications commonly used in the fitness industry, sports science, and physical education. By the end of this you will see and understand the issue from the genetic perspective.

The term the question refers to is “somatotype.” Somatotype evaluation was developed in the 1940s by psychologist William Herbert Sheldon and it had nothing to do with physical fitness. It was a subjective evaluation used to determine general psychological traits:

- Ectomorphic: characterized as linear, thin, usually tall, fragile, lightly muscled, flat chested and delicate; described as cerebrotonic inclined to desire isolation, solitude and concealment; and being tense, anxious, restrained in posture and movement, introverted and secretive.

- Mesomorphic: characterized as hard, rugged, triangular, athletically built with well developed muscles, thick skin and good posture; described as somatotonic inclined towards physical adventure and risk taking; and being vigorous, courageous, assertive, direct and dominant.

- Endomorphic: characterized as round, usually short and soft with under-developed muscles and having difficulty losing weight; described as viscerotonic enjoying food, people and affection; having slow reactions; and being disposed to complacency.

As a psychological profiling tool, somatotype was soundly crushed for good reason. You simply cannot subjectively judge people’s psychology and behavior based on their physical appearance and body composition. It’s true that some general conclusions can be drawn, but they cannot be universally applied and they usually don’t apply to the mind as much as to the endocrine system. The truly dark side of this taxonomic idea was that Sheldon was one of the leaders of a school of thought, popular in anthropology at the time, which held that the size, shape, and composition of a person’s body indicated intelligence, temperament, moral worth, and future achievement. His work went on to be used in eugenics and while all of this is deeply immoral and nasty business, I am happy to report that something positive did emerge.

The one thing Sheldon was right about was the existence of different general body types and the fact that you could extrapolate certain information from those body types. In fact, much of the information he originally posited was correct. It just all fell apart when he tried to infer a person’s value, morality, etc to the equation.

In reality, we can easily subjectively evaluate a great many things about health and physical performance from external observation. Indeed, a person’s genetic disposition and physiological function are on full and open display. The implications and facts of this consume many large volumes in your local library.

What then is the downstream consequence of somatotype? In ensuing decades, somatotype shifted away from it’s original use and mathematical formulas were developed to refine the concept for anthropomorphic research. According to Dr. Rob Rempel ofSimon Fraser University, “With modifications by Parnell in the late 1950’s, and by Heath and Carter in the mid 1960’s somatotype has continued to be the best single qualifier of total body shape.”

That body shape issue has a lot of implication down the road when combined with physics. This is also where we dive into genetics.

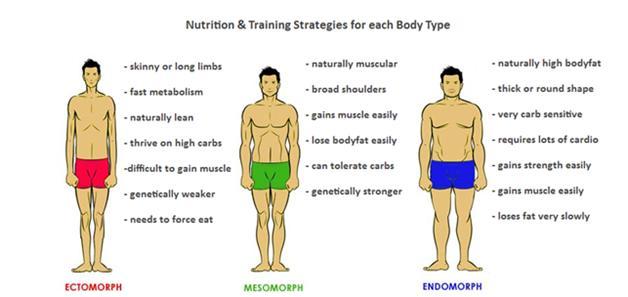

When it comes to training and or changing a person, there are things we can or cannot do. For example, we can use diet and exercise to modify muscle mass and fat mass to a certain extent. We can use pharmacology to further alter a person’s physiology. The list of things we can do is amazing these days. However, we cannot change the width of a person’s pelvis or shoulder girdle. We cannot elongate or shorten the long bones of the body. Nerve conduction rates are relatively finite. We cannot improve a number of neuropsychological issues without increasing IQ, which cannot be done. We can only improve VO2max by about 15%. The list goes on and on. So now, what does this mean in the long run? The chart below shows us where on the performance spectrum we land on average.

Returning to our original question, let me now elaborate on the answer. As you can see from the chart, certain body types are genetically disposed to certain sports, professions, etc. But, does that change the training? The answer is no. You still train everyone the same way. However, how far they can go is what their genetics dictate. No matter what you do, there is no special secret training routine to make Refrigerator Perry the next Kona Ironman winner anymore than we can make Jan Frodeno the next starting center for the Chicago Bears.

At this point there will likely be a number of people jumping up and down thinking they have examples to prove me wrong, if only partially. For example, how to we pack on a bunch of muscle onto a skinny tall kid? People will reference the fact that he needs a ton of hypertrophy volume work and it can be done. To a limited extent, sure. Just like a big fat guy can be slimmed down using high volume intensive aerobic work… To a limited extent. Endos and ectos can alway move toward the center meso and the meso can move toward the endo or ecto side of the spectrum, but they can never overlap. You can’t out train your skeletal anatomy or a great many physiological genetic presets. These arguments are actually just confusion over the fact that form follows function to the limits of one’s genetic potential and the methods of training remain the same for all.

Your turn! Let me know if this cleared things up for you or not in the comments below or on social media.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Originally published at Nate’s site

[jetpack_subscription_form]

Brought to you by the dudes at Spotter Up