The Last Full Measure movie was to tell us the story about Air Force Pararescue Jumper (PJ) William H. Pitsenbarger, the soldiers of Charlie Company Army, 1st Infantry Division (the Big Red One) during the Battle of Xa Cam My (1966), during some of the bloodiest days of the Vietnam War. But it was never made. It should be.

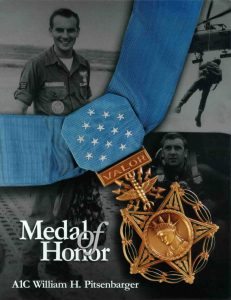

The Last Full Measure movie was to tell us the story about Air Force Pararescue Jumper (PJ) William H. Pitsenbarger, the soldiers of Charlie Company Army, 1st Infantry Division (the Big Red One) during the Battle of Xa Cam My (1966), during some of the bloodiest days of the Vietnam War. But it was never made. It should be.“Air Force Pararescue Jumper, William H. Pitsenbarger, saved the lives of a bunch of mud soldiers whom he did not know before perishing. He was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor after a young Washington bureaucrat teamed with veterans of Operation Abilene and Pitsenbarger’s father and convinced Congress to reconsider the legacy of his sacrifice 34 years after his death.”

Pararescuemen are Air Force special operatorions members who officially serve as medics rescuing downed and injured aircrew members in austere and non-permissive environments. Pararescue Jumpers, commonly known as PJ’s, often serve outside their formal role rescuing folks anywhere from distressed Chinese sailors in the Pacific to Hurricane Katrina victims in New Orleans.

Pararescuemen are among our nation’s elite fighting forces often being attached to joint missions, which includes attachments with Navy SEALS and Army special operations units respectively. Unlike the Green Berets and Navy SEALS, however, Pararescuemen have not been featured in much of the popular culture. Recently (2012), the movie Act of Valor did an excellent job of picturing the amazing things Navy Seals do, and it was filmed using active-duty Navy Seals, to picture real-life heroism. In Hollywood, the mixture of sex and violence sells and it’s always more lucrative than making stories about honorable deeds and saving lives.

Once in a while Hollywood does something great by making movies like Glory and Saving Private Ryan. We haven’t seen a great feature film about a Pararescuemen since 1964. It would be a real treasure for audiences to see the story about this great hero.

In 2010, it was announced that director Todd Robinson was working on the story of A1C William H. Pittsenberger in a film being called “The Last Full Measure.” Pittsenberger was a young man who knew and believed in what he was about from the beginning. According to the National Museum of the Air Force website, Pittsenburger wanted to drop out of high school to join the Army and try out for Army Special Forces.

Though the site doesn’t say so, I imagine he would have been a combat medic. Eventually Pitsenburger was persuaded by his parents to graduate and in 1962 he joined the Air Force and volunteered for Pararescue.

The Pararescue training pipeline, as it is known among the PJs, has always been a highly selective and long, roughly two year, haul through the various schools. Facets of the school have changed over the years, but today’s PJ’s go through roughly the same Indoctrination course as the old school.

In addition to the rigors of drown-proofing water-confidence drills, endless calisthenics, various team building exercises, and great miles of running, Indoc candidates were, and are today, tested on their character: their ability to face challenges regardless of the intense the workload.

They must never quit.

One PJ I spoke with, who graduated from Indoc in the early 70’s, told me how after doing something wrong the cadre made him carry two milk jugs filled with water, and tethered by a rope around his neck, everywhere he went — even with him to bed — for the remainder of the Indoc course.

One day upon being summoned in front of the cadre, Jerry tells me, he and his teammate were ordered to “drop.” So, drop they did and began performing push-ups. But Jerry was slow due to the weights around his neck. When the cadre asked Jerry why he could not perform the push-ups with his teammate, why he was making his teammate look so bad, why he was even on this team because his discipline was so pathetic, Jerry replied strained and out of breath:

“Hooya sergeant! It’s… it’s hard doing push-ups with, with big jugs!”

Jerry told me at that point the cadre, dying of laughter, had them recover and return to whatever they were doing.

Levity is an important aspect of stress control, but with a graduation rate of about twenty percent, those who volunteer for Pararescue, and make it, have a purpose motivating them far beyond the training pipeline and down range where anything can happen.

Pararescumen have a motto they live by engrained in them from the very beginning of training: “These Things We Do, That Others May Live.” That selfless code applies to the way these men relate with their teammates as well as those they rescue. If one survives the Pararescue training pipe, That Others May Live is undoubtedly a philosophical impetus etched in behind the character of every Pararescueman in and out of their professional call of duty.

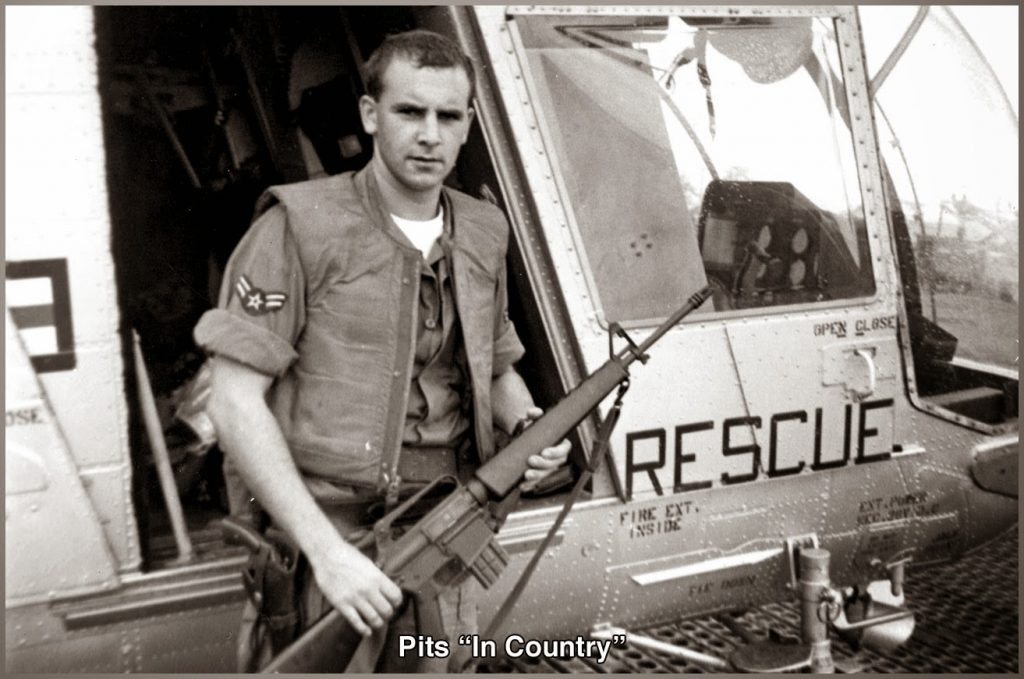

Pitsenbarger was 21 in the spring of 1966 and was already in the last months of his enlistment. He had been looking into a civilian career as a medical technician, and with months before he got out, applied to and planned on attending Arizona State University. He had completed over 300 rescue missions by this point in his career, many of them down range and of enemy fire.

On April 11 of that same year, in the middle of the afternoon, his unit was alerted: members of the Army’s 1st Infantry Division were pinned down in tall, suffocating, thick jungle near Saigon. It was impossible to land a chopper. They used HH-43 Huskies in those days equipped with hoist cables to lower and raise litter baskets with patients in them; a real life-line.

Though Pitsenbarger was off duty he volunteered for the mission and was flying over the jungle canopy within minutes. Upon reaching the area Pitsenbarger volunteered to be lowered down to help the wounded and as John Frisbee, of Neil AF Magazine (1983), narrates:

It was standard procedure for a pararescue medic to stay down only long enough to organize the rescue effort. Pitsenbarger decided, on his own, to remain with the wounded. In the next hour and a half, the HH-43s came in five times, evacuating nine wounded soldiers. On the sixth attempt, Pitsenbarger’s Huskie was hit hard, forced to cut the hoist line, and pull out for an emergency landing at the nearest strip. Intense enemy fire and friendly artillery called in by the Army made it impossible for the second chopper to return.

Heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire was coming in on the Army defenders from all sides while Pitsenbarger continued to care for the wounded. In case one of the Huskies made it in again, he climbed a tree to recover the Stokes litter that his pilot had jettisoned. When the C Company commander, the unit Pitsenbarger was with, decided to move to another area, Pitsenbarger cut saplings to make stretchers for the wounded. As they started to move out, the company was attacked and overrun by a large enemy formation.

By this time, the few Army troops able to return fire were running out of ammunition. Pitsenbarger gave his pistol to a soldier who was unable to hold a rifle. With complete disregard for his own safety, he scrambled around the defended area, collecting rifles and ammunition from the dead and distributing them to the men still able to fight.

It had been about two hours since the HH-43s were driven off. Pitsenbarger had done all he could to treat the wounded, prepare for a retreat to safer ground, and rearm his Army comrades. He then gathered several magazines of ammunition, lay down beside wounded Army Sgt. Fred Navarro, one of the C Company survivors who later described Pitsenbarger’s heroic actions, and began firing at the enemy. Fifteen minutes later, as an eerie darkness fell beneath the triple-canopy jungle, Pitsenbarger was hit and mortally wounded. The next morning, when Army reinforcements reached the C Company survivors, a helicopter crew brought Pitsenbarger’s body out of the jungle. Of the 180 men with whom he fought his last battle, only 14 were uninjured.

It would be over 30 years before the heroic actions of Pitsenbarger were recognized and nominated for the Medal of Honor. The Nation Museum of the Air Force website states “He descended a hundred feet into the firefight with a medical bag, a supply of splints, a rifle and a pistol.” The Huskies flew home 9 lives on several trips thank to Pits, as his friends called him, and countless others have been inspired since by the selfless character, valor, and how he laid down his life that others may live.

That Others May Live may be a motto leading some to honorably give their “last full measure of devotion,” as the Gettysburg Address states, and that is a great title for a film of this nature, but what is the nature of this film anyway? We do not know of course, all we know is the background and title, but that title is an interesting one. I sure don’t know, but I’ve been watching for this film over a year now and look forward to how they treat the subject, if they ever will.

The film was supposed to star Aaron Eckhart, Morgan Freeman, Bruce Willis, Robert Duvall, Andy Garcia, Laurence Fishburne, Amy Madigan, and “others.” According to aceshowbiz.com, we may see Charles Matthew Hunnan, of Sons of Anarchy fame, as Bill Pitsenbarger. I pulled the film’s poster image from RCR website, which offers no further information on the film except it will debut in 2014, which at the time of this writing, is nearly three years passed due. Let’s hope someone in Hollywood will make this movie.

Citations

Occasionally a movie is made that helps a veteran find peace within themselves. This is one of those movies! It shows the true relationships between combat veterans and the bond they share battling the forces that control commendations with a pen rather than a patch.