After the ankles, a tight and excessively kyphotic thoracic spine is the next place to look. This forward rounding of the upper back shifts the shoulders forward (the base of the arms), which again means the arms need to angle back farther than normal, which exacerbates the other problem of not being able to secure the shoulder blades in a strong retracted position to create the stable base necessary.

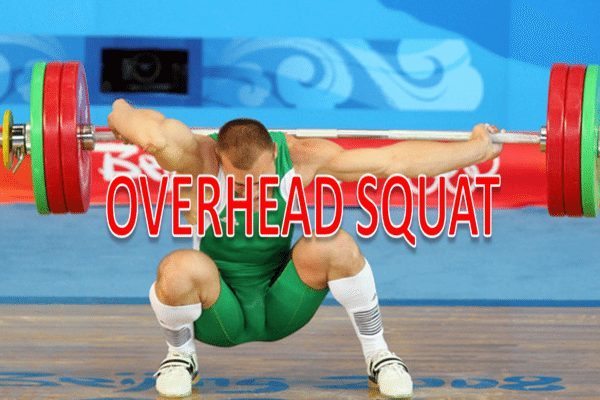

Five Errors in the Overhead Squat & Going Overhead

- Overhead Position: Every OHS should start and finish with the bar directly over the center of pressure in the foot. What that means is likely the bar should start and stay over the back of the ear with the armpits turned out and shoulders externally rotated. This is easy to spot as a coach as you just need to ensure that the athlete has their armpits facing forward. If their armpits are facing down, then their shoulders are internally rotated and in a dangerous position. Also, if the athlete hyper-extends their back and allows the bar to shift to well behind their center of pressure then not only is their back position compromised but their shoulder girdle is now at risk. Put the bar over the back of the ear and keep it there for the entirety of the movement.

- Foot Position: The feet MUST stay just outside the hips. The reason for this is to allow the hips to squat right in between the heels. This does two things for the lifter. First, it keeps the lifter upright and maintains a vertical torso. Second, it allows the lifter to keep their hips under the bar which allows the bar to be more stable over the center of gravity. Often you will find athletes try to go too wide with their feet compromising their depth and preventing their knees from tracking over their toes. Furthermore, you may find athletes struggle to complete an OHS when their feet are too narrow. A narrow stance requires extreme ankle and hip flexibility and will create more problems for those without such capability.

- Hip, Ankle, Thoracic Spine, and Shoulder Mobility: The #1 culprit in the OHS for most athletes is mobility. Our culture promotes a sedentary, sitting lifestyle that often causes all kinds of immobility. In order to properly execute an OHS, the athlete must be able to flex the ankle to some degree. This allows the knees to push toward the toes in order to allow the hips to stay near the heels and torso to stay vertical. Furthermore, an athlete must have the hip flexibility to allow the hips to squat near the heels and keep the torso vertical. Added to the hips and ankles, a proper OHS requires the ability to extend properly the thoracic spine (aka upper back). This capability allows for the shoulders to properly externally rotate and for the chest to stay upright during the squat. If your rhomboids, traps, and posterior deltoids (when inactive) are not mushy and soft, they need to be. Lastly, and likely the last culprit you should check is shoulder mobility. Obviously an athlete completing an OHS must have the ability to externally rotate the shoulders, retract the scapula, and remain stable in that position overhead. Word of warning though: don’t let thoracic spine immobility trick you into thinking the problem is shoulders. Check the T-spine first.

- Posterior Chain and Glut Activation: Last but not least is the dreaded inactive gluts. I have commented on this before but it shows up massively in the OHS. If your low back and gluts are not active as you squat three things happen. First, your hips push back as you squat leaving your hips well behind your heels and your torso more angled forward. Active gluts forces them forward. Second, your knees fall into a valgus position. Active gluts force the knees to stay over the toes where they should be. Lastly, the low back rounds and the dreaded “butt wink” appears. Most of the times this is because of laziness as the athlete doesn’t think to activate and stay active in their posterior chain and gluts but often this can be a motor function training issue. Some athletes simply have a hard time telling their gluts or the entirety of their posterior chain to turn on and stay on. There are a ton of simple drills to help that. Basically google glut bridge and get friendly with your GHD.

- Limited shoulder flexion (short/stiff lats, long head of triceps, teres major, inferior capsule)

- Limited shoulder external rotation (short/stiff pecs, lats, subscapularis)

- Lack of scapular upward rotation (weakness of lower traps, upper traps, and/or serratus anterior; and dominance of levator scapula, rhomboids, and pec minor)

- Poor thoracic spine extension

- Lack of anterior core stiffness

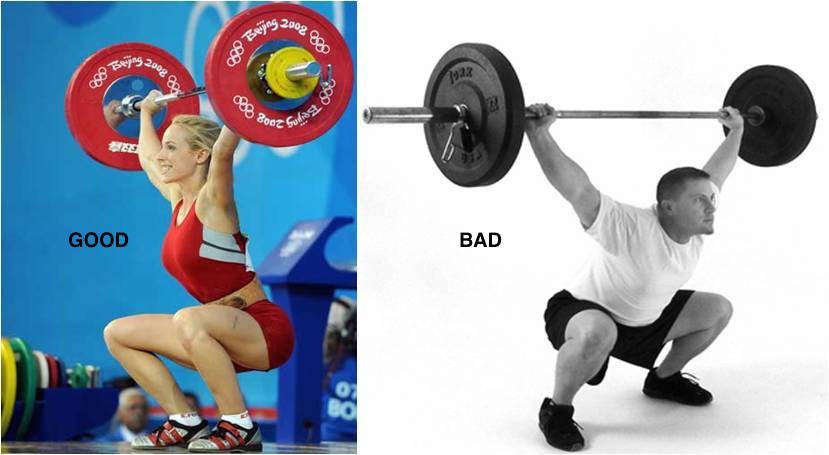

So here are a few shots of what is good, what is not good, and what a disaster looks like. Note the overhead squat (OHS) is primarily a developer of agility, balance, mobility, and stability (yes that’s another way to develop strength).