1964. Beautiful picture of my father in Vietnam. 25 years old in a road side shack on the road to Pleiku. Traveling from Quy Nhon Vietnam. Dangerous road for an American without a military escort.

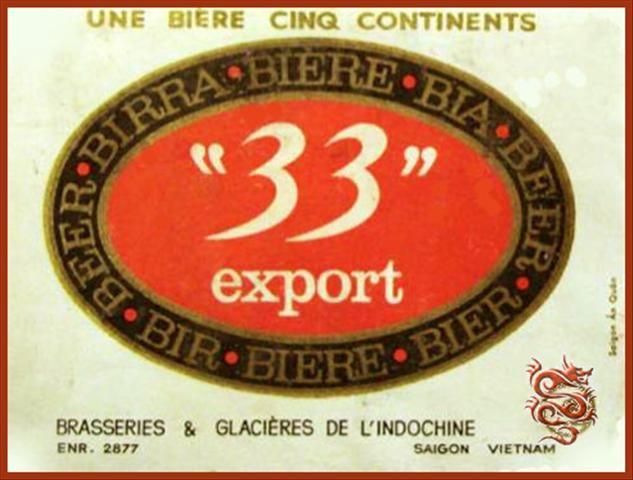

During the Vietnam War, the United States exported various domestic beer brands to South Vietnam, including Pabst Blue Ribbon, Schlitz, and Budweiser. However, two local options, 33 Beer and Tiger Beer, were more affordable and consistently available when American brands were scarce. My father told me that 33 Beer was the most popular among his group of drinking buddies. The popular 33 Beer, known as “Ba Muoi Ba” in Vietnamese, had its origins in France (as Bière 33) in the late 19th century, following a German recipe. The label “33” was a nod to its original 33-centiliter (11.2-ounce) bottle size. It is a rice beer.

A brewery was established in Saigon by France in the early 20th century, and production continued when South Vietnam gained independence. It gained popularity among American GIs during the 1960s and 1970s during the Vietnam War. It has been renamed to 333 Premium Export Beer, commonly known as 333. with the fall of South Vietnam to the North Vietnamese and the rise of the communist government, the beer underwent a name change to “333 Premium Export Beer” to distance itself from its colonial origins. In 1994, 333 Premium Export Beer became available in the American market, and it is also distributed in Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and Australia.

Another staple lager in southern Vietnam was Bière Larue, first brewed in Saigon in 1909 by Frenchman Victor Larue. While officially named Bière Larue, it was commonly referred to as Tiger Beer due to the label’s image. Both brands maintained their original brewing recipes and processes in the 1960s and ’70s. Bière Larue is still produced by Vietnam Brewery Ltd. and should not be confused with the Singaporean brand Tiger Beer, also sold by the same company. Both 333 and Bière Larue continue to be lagers, but their recipes have evolved since the Vietnam War to cater to modern and more international tastes.

American service members noted that Vietnamese beers sometimes exhibited varying tastes, occasionally featuring bitter notes, a hint of vinegar aftertaste, or an odor reminiscent of formaldehyde, a chemical used in construction materials, industrial disinfectants, and funeral home and medical lab preservatives. I asked my dad about that story. He stated that it wasn’t so, however the taste of the beers were sometimes inconsistent. Inconsistencies in storage conditions and occasional issues with raw materials could result in variations in quality from one batch to another. Despite the widespread speculation, there is no evidence to support the belief that 33 Beer and Tiger Beer contained formaldehyde. Minimal amounts of formaldehyde are naturally produced during the fermentation process in brewing, a phenomenon common to all beers, as opposed to intentionally adding formaldehyde as a preservative.

Photo G3263 PFC Thomas D. Corneilus (left front), SP4 Charles J. Morris (left rear), and PFC Jerry W. Ryan of the 148th MP Platoon, 188th MP Company, 92nd MP Battalion, enjoying a cold beer with a Vietnamese Army Quan Canh (MP) in Vinh Long, Mekong Delta, IV Corps Tactical Zone in 1968. Courtesy of SP/4 Fred L. Webb, 148th MP Platoon, attached to 557th & 300th & 188th MP Company, 95th & 92nd MP Battalion’s, 89th MP Group, 18th MP Brigade, Vinh Long, Vietnam.

American canned beers exported to Vietnam did not feature the then-new “pop-top” opener; instead, troops needed a “church key” can opener or another sharp tool to puncture the lids. Furthermore, the two Vietnamese beers had slightly higher alcohol content compared to their American counterparts, about 5.5 percent versus the 3.2 to 5 percent range. Similar to Budweiser but unlike most other U.S. brands of that time, Vietnamese beers incorporated fermented rice in their brewing process.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.