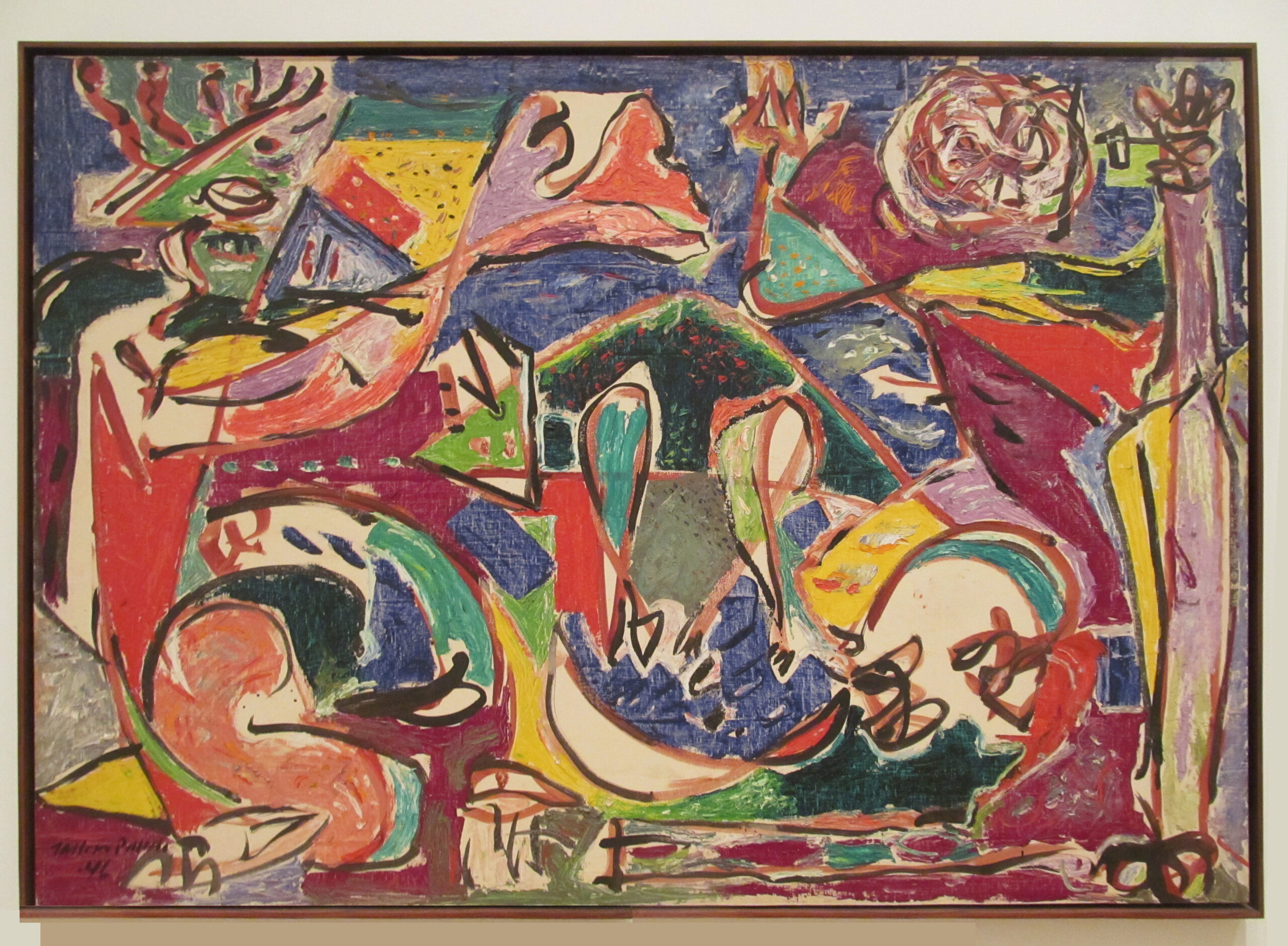

The Key 1946. Jackson Pollock. Oil on linen. Art Institute of Chicago. It’s believed that painting was named “The Key” to signify a new beginning in American art, during an era when European artworks held sway over the art world. Photo: Rob Corder / CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED.

“The modern artist… is working and expressing an inner world – in other words – expressing the energy, the motion, and other inner forces.” — Jackson Pollock

In the aftermath of World War II, a new art movement known as Abstract Expressionism emerged from obscurity to establish New York as the center of the art world. Key figures in the New York School, which was the epicenter of this movement, included such artists as Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Norman Lewis, and Willem de Kooning, among others. This movement rapidly gained international prominence. However, the swift rise of Abstract Expressionism led to rumors and speculations about the factors behind its success.

Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism is an art movement that originated in New York in the 1940s. It became a dominant trend in Western painting during the 1950s. This movement is often characterized by gestural brushstrokes or mark-making, and the impression of spontaneity. It focuses on a shared curiosity in the utilization of abstraction as a means to express and/or elicit emotion through artistic works.

The movement comprised many styles varying in both technique and quality of expression. Abstract Expressionism is known for its focus on spontaneous, automatic, or subconscious creation. The artists associated with the movement combined the emotional intensity of German Expressionism with the radical visual vocabularies of European avant-garde schools like Futurism, the Bauhaus, and Synthetic Cubism.

Abstract Expressionism was seen as rebellious and idiosyncratic, encompassing various artistic styles, and was the first specifically American movement to achieve international influence and put New York at the center of the Western art world, a role formerly filled by Paris. It led to the development of several post-war art movements and styles, including Pop art, Minimalism, and Neo-expressionism, influencing a diverse range of European and American artists that followed.

During their formative years, the Abstract Expressionists were immersed in a rich and diverse cultural environment, akin to a museum without walls. This environment was filled with a plethora of sources, references, and inspirations that contributed to the unique and idiosyncratic nature of Abstract Expressionism. The movement’s complexity and diversity defied simple categorization, making it difficult to confine within the boundaries of a traditional ‘movement’.

In the wake of the war, artists such as Piet Mondrian, Salvador Dalí, and Max Ernst found themselves displaced. These artists played a crucial role in challenging and reshaping American perceptions of Modern European art. They introduced innovative techniques like psychic automatism, further enriching the artistic landscape.

The legacy of Abstract Expressionism was carried forward by the inventive second-generation artists. They breathed new life into modern painting, a tradition that continues to thrive today. Many contemporary artists draw inspiration from this movement, underscoring the enduring impact of Abstract Expressionism on the art world. It paved the way for America’s dominance in the global art scene.

The CIA’s Role

Unbeknownst to many, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) covertly supported the Abstract Expressionist movement. This support was part of a policy known as the “long leash”, similar to the indirect CIA backing of certain publications. The decision to include culture and art in the United States Cold War arsenal was taken as soon as the CIA was founded in 1947. The CIA funded exhibits all over the world to promote the idea that a culture rooted in freedom was superior to one steeped in repression.

The CIA perceived it as a reflection of the United States as a sanctuary for free thought and open markets. It also viewed it as a counterpoint to the socialist realist styles that were common in communist countries and a challenge to the dominance of the European art markets.

The CIA gave the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) a five-year grant of $125,000 to fund the museum’s International Program, which was responsible for loaning its collections to European institutions. By 1956, MoMA had organized 33 international exhibitions devoted to Abstract Expressionism, all funded by the grant.

The CIA also secretly funded the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an organization promoted by the United States with offices in up to 35 countries. It organized cultural events such as conferences, exhibitions, concerts, and even published over twenty prestigious magazines. This organization also served as the official sponsor of touring exhibitions.

The CIA also covertly promoted the purchasing of works by private collections. This was done in an effort to use Abstract Expressionism as a form of benevolent propaganda, in sync with the post-war political ideology of the American government.

The Impact

The CIA’s promotion of Abstract Expressionism had a significant impact on the art world. It helped shift the focus of the art world from Paris to New York. In 1957, a year after Pollock’s death, the Metropolitan Museum of Art paid an unprecedented sum for his painting, Autumn Rhythm. The following year, The New American Painting, an influential exhibition organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, began a year-long tour of European cities.

The CIA’s involvement in promoting Abstract Expressionism illustrates the complex interplay between art and politics. While the artists may have been unaware of the CIA’s role, their work served as a powerful tool in the ideological battle of the Cold War. It serves as a reminder of the potential for art to be used as a vehicle for political messaging and propaganda.

Resources

Central Intelligence Agency

CIA.gov

Museum of Modern Art

MoMA.org

Metropolitan Museum of Art

MetMuseum.org

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.