Pollice Verso (“With a Turned Thumb”), an 1872 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

In the grand amphitheaters of ancient Rome, where the sun beat down upon the sand-strewn arena, the gladiators stood as both warriors and entertainers. Their lives were a paradox—a blend of brutality and honor, fame and anonymity. From the blood-soaked battles to the shared meals and rituals, they etched their legacy into history. These men, often slaves or condemned prisoners, fought not only for survival but also for the fleeting glory that came with each swing of their swords. As the crowds roared and the dust settled, the gladiators left an indelible mark on the collective memory of humanity — a testament to courage, sacrifice, and the enduring fascination with mortal combat.

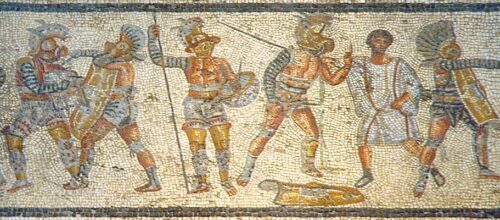

Roman gladiators fought before the public in organized games held in large purpose-built arenas throughout the Roman Empire from 105 BC to 404 AD (official contests). These contests were often to the death, resulting in a short life expectancy for gladiators. Most fighters were slaves, former slaves, or condemned prisoners.

The world of Roman gladiators was steeped in tradition and ritual, both inside and outside the arena. The origins of gladiatorial fights trace back to funeral rites. Early Romans believed that the souls of the dead required blood to be appeased. Gladiatorial contests were a form of human sacrifice, held to honor great men and women at their funerals. These events were not uncommon in the ancient world, and they evolved into the bloody spectacles we associate with gladiators.

The Campanians, descendants of Greek settlers, popularized gladiatorial fights about a century before the death of Brutus Pera. Borrowing from their ancestral homeland, they began the tradition to celebrate a military victory over their archenemies, the Samnites. They dressed slaves in captured Samnite armor and forced them to fight to the death.

The Romans were influenced by their predecessors, the Etruscans, in organizing gladiatorial games. Some scholars attribute the origins of funerary gladiatorial traditions to Etruria, a region north of Rome. Etruria significantly influenced Roman culture and was eventually conquered by Rome. These rituals involved bloodshed, meat distribution, and the passage of souls to the afterlife. Although later official Roman contests discarded the religious element, vestiges remained in the act of finishing off fallen gladiators.

The gladiatorial match held to honor Brutus Pera comprised six gladiators fighting with the weapons and armor of the Thracians (people from present-day Bulgaria). Blood was spilled, and meat and wine were shared during these events. The plebeians of Rome developed a taste for these brutal spectacles.

Roman gladiator games were an opportunity for emperors and aristocrats to display their wealth, commemorate victories, and distract the populace. These events were held in massive arenas throughout the Roman Empire, with the Colosseum being the largest. Contrary to popular belief, gladiators did not salute their emperor with the line: “Ave imperator, morituri te salutant!” (Hail, Emperor, those who are about to die salute you!

The fascination with these bloody spectacles made them one of the most-watched forms of popular entertainment in the Roman world. Spectators from all sections of Roman society flocked to witness gory spectacles where gladiators, symbols of honor and courage, employed their martial skills in kill-or-be-killed contests.

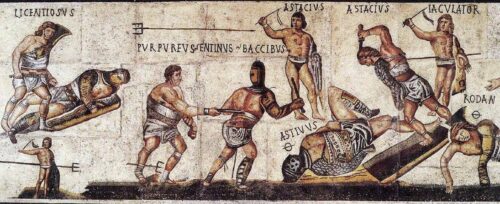

Types of Gladiators

In ancient Rome, there were diverse types that graced the arenas of ancient Rome, each with distinct fighting styles and equipment. Here are some notable ones:

Retiarius: The Retiarius, aptly named the “net fighter,” had a unique combat style. Armed with a trident and a cast net, this gladiator relied on agility and speed.Their minimal armor allowed them to move swiftly. Retiarii often faced off against the Secutor.

Secutor: The Secutor, meaning “pursuer,” was a heavily armored gladiator. Equipped with a large shield and a short sword (gladius), they were designed to chase down and engage the Retiarius. Symbolizing courage and determination, Secutors were crowd favorites.

Thraex (Thracian): Modeled after Thracian warriors, the Thraex was a formidable opponent. They wielded a curved sword called a sica and carried a small rectangular shield.Their distinctive helmet featured a wide-brimmed crest. Thraex fighters often clashed with Murmillos.

Murmillo: The Murmillo donned a fish-crested helmet and carried a gladius (short sword).Their large rectangular shield (scutum) provided excellent protection. Typically, Murmillos faced off against Thraex or Hoplomachus.

Hoplomachus; The Hoplomachus was an armed fighter. They wore a helmet, greaves (leg armor), and carried a spear and a small round shield.Adapted from Greek hoplites, they engaged in close combat.

Gladiatrix: Although rare, female gladiators (Gladiatrices) existed. They fought in various styles, sometimes emulating male gladiators. Their presence challenged gender norms in the arena.

Provocator; The Provocator, known as the “challenger,” wore heavy armor. Armed with a gladius, they were skilled combatants. Provocatores engaged in intense battles, captivating the audience.

Gladiator Schools

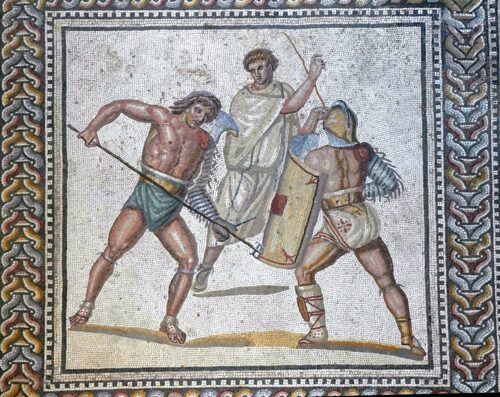

Roman gladiators underwent rigorous training to prepare for their brutal battles in the arena. Gladiators lived and trained in schools called ludus gladiatorius. These schools were part of the larger infrastructure that produced gladiatorial fights called munera (Latin for “duty” or “obligation”). Their training was rigorous, focusing on combat skills, endurance, and discipline.

Gladiators trained under experienced instructors in the ludus. They practiced with swords, tridents, nets, and armor. Familiarity with armor’s weight and restrictions was crucial for effective maneuvering in battle. They repetitively practiced sword combinations against vertical stakes using wooden weapons twice the weight of normal ones. Experienced gladiators also sparred with each other, sometimes using sharp weapons.

Physical Fitness Training

The physical fitness of gladiators was paramount to their survival and success in the arena. Gladiators faced life-or-death battles, requiring peak physical condition. Rigorous training built strength, agility, and endurance, ensuring they could withstand the grueling fights. Gladiators needed stamina to endure prolonged fights. Proper training also emphasized recovery, allowing them to heal between bouts. Fit, muscular gladiators captivated audiences. Their physiques symbolized courage and prowess, drawing cheers from the crowd.

Physical training employed a comprehensive workout routine that combined these elements:

Milo of Croton’s Progressive Overload:

Milo, the legendary wrestler from ancient Greece, embodied the concept of progressive overload. According to historical accounts, he would carry a young calf on his shoulders each day. As the calf grew into a full-grown bull, Milo’s strength increased proportionally. This consistent, incremental challenge allowed him to develop immense physical power and endurance over time..

Spiculus and the Tetrad System:

Spiculus, regarded as the greatest gladiator of his time, followed what was known as the “Tetrad System”. It divided training into four-day cycles, with each day focusing on a different type of training.

Day 1: Preparation with short, high-intensity workouts (similar to today’s HIIT and sprints).

Day 2: Intense, all-out exercises (equivalent to squats, deadlifts, and pull-ups).

Day 3: Rest or light activity for recovery.

Day 4: Medium-intensity exercises, focusing on skill work.

Galen’s Principles:

Galen, an esteemed physician who attended to numerous gladiators, emphasized two crucial aspects of their training:

1. Varying Intensity:- Gladiators gradually increased the intensity of their workouts over time. – Rather than starting at full speed, they followed a progressive approach, allowing their bodies to adapt and improve.

2. Cool-Down: After intense training sessions or battles, proper cool-down was essential. Gladiators engaged in specific post-workout activities to aid recovery and prevent injury.

Diet

Roman gladiators had a diet that was mostly vegetarian. An analysis of bones from a cemetery where these arena fighters were buried revealed fascinating insights into their nutrition. The study, conducted by academics from the Medical University of Vienna in Austria and the University of Bern in Switzerland, sheds light on their eating habits.

The typical food consumed by gladiators included wheat, barley, and beans. Their meals were rich in complex carbohydrates. Interestingly, this echoes the contemporary term for gladiators as the “barley men”, There was little sign of meat or dairy products in the diet of almost all these professional fighters. Despite the popular belief that gladiators were exclusively slaves, their primarily vegetarian diet was not a consequence of poverty or slave status. So, contrary to the chiseled, meat-centric image often portrayed, Roman gladiators relied on a carb-heavy, mostly plant-based diet to fuel their intense battles in the arena.

Olive oil also played an important role in the diets of gladiators. Rich in healthy fats, olive oil not only enhanced the flavor of their meals but also provided a concentrated source of energy.

Hydration Practices

Gladiators recognized the importance of staying hydrated. Water was their primary source of hydration during training and battles. Interestingly, wine was also a common beverage for gladiators. It served both as a source of hydration and a means to lift their spirits during arduous times. In ancient Rome, the practice of mixing wine with water was common. Both Greeks and Romans diluted their wine, although technically they were adding wine to their water more than the other way around.

Recent research suggests that gladiators may have consumed a special energy drink made from the ashes of charred plants. These ashes were a rich source of calcium. While this “Gladiator Gatorade” is intriguing, it highlights their resourcefulness in seeking optimal nutrition.

Life of a Gladiator

The life of a Roman gladiator extended beyond the blood-soaked sands of the arena. However, for every epic story of a gladiator becoming a legend of the arena and winning fame and freedom, thousands of others died anonymously on the sand. They led violent, dangerous lives, subject to the whims of their superiors. Some managed to overcome these circumstances and became celebrities, but they were a very small minority.

Their Legacy Continues

And now, in the 21st century, their legacy continues. Ridley Scott, the visionary director behind the original Gladiator film, is resurrecting the epic saga. Gladiator II is set to grace the big screen, transporting audiences back to the heart of ancient Rome. Scheduled for release in November 2024, this sequel promises to reignite the passion for gladiatorial combat, weaving new tales of valor, betrayal, and vengeance.