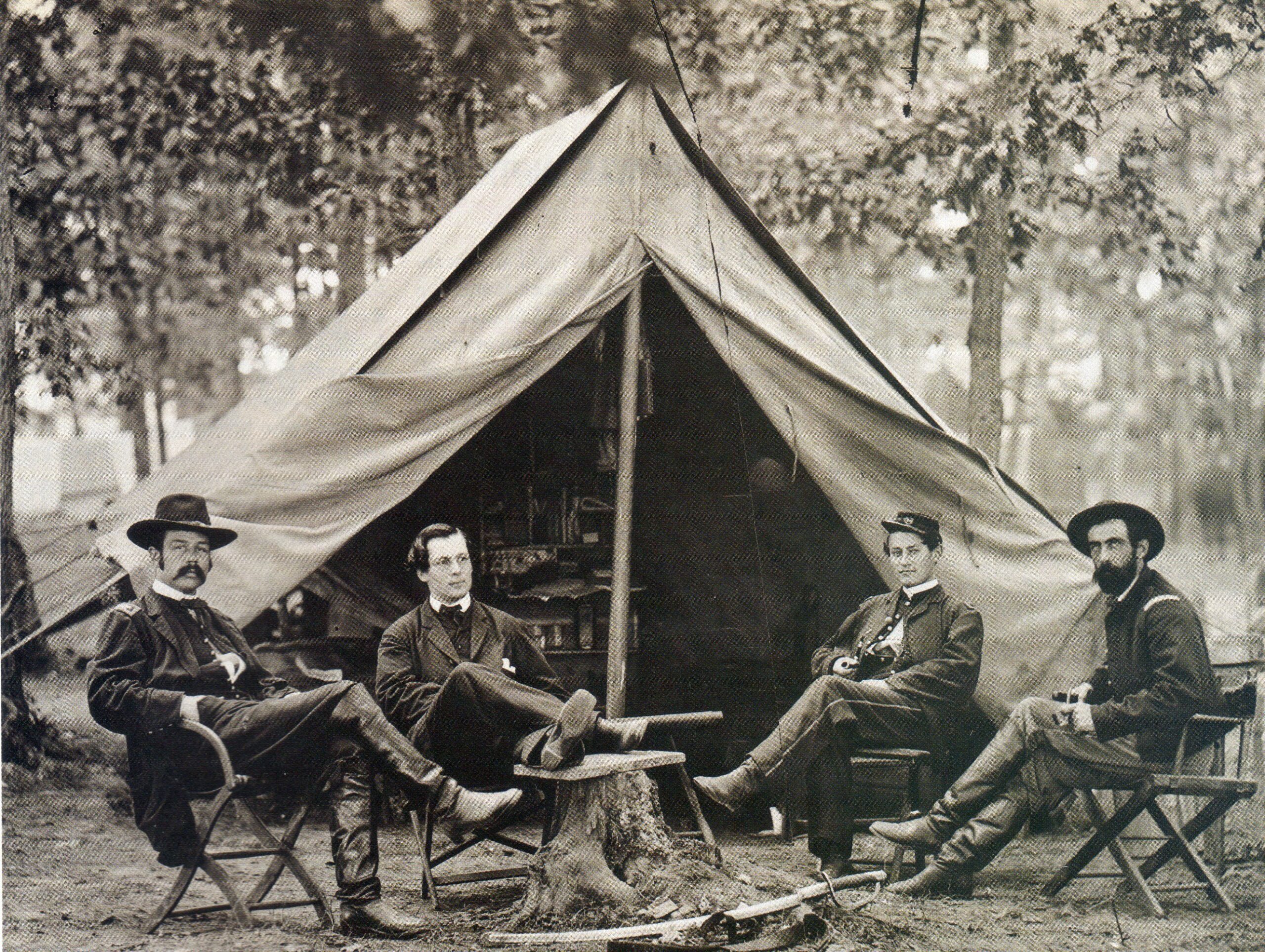

Col. George Henry Sharpe sits at far left with other members of his “Bureau of Military Information”, John C. Babcock, unidentified officer, and Lt. Col. John McEntee, February 1864. Photo taken in the store shop inside the Lincoln Memorial in 2000 at Washington D.C. Credit: GoShow / CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED.

The Bureau of Military Information (BMI), established in 1863, was the first formal and organized American intelligence agency, active during the American Civil War. The BMI was a significant development in wartime espionage operations, providing a more structured military intelligence organization than those of rival detectives Allan Pinkerton and Lafayette Baker.

In January 1863, Major General Joseph Hooker, newly appointed to lead the Army of the Potomac, ordered one of his regimental commanders, 34-year-old Colonel George Sharpe, to establish a formal intelligence service. This led to the formation of the BMI. Sharpe, a New Yorker and an attorney before the war, was assisted by John C. Babcock, a civilian and former employee of Pinkerton. On 11 February 1863, they established the Bureau of Military Information.

The BMI differed from other Union intelligence agencies during the Civil War in several ways:

1. Formal Organization: The BMI was the first formal and organized American intelligence agency. While other Union intelligence initiatives were decentralized, the BMI provided a more structured military intelligence organization.

2. All-Source Intelligence Analysis: The BMI collected information from a variety of sources, including Confederate deserters and prisoners, former enslaved people, captured documents, and Southern newspapers. This information was then combined with data from other sources, such as reconnaissance balloons, intercepted telegraph messages and flag signals, and other Union cavalry units. This approach of integrating information from multiple sources is known today as all-source intelligence analysis.

3. Field Agents: The BMI utilized around 70 field agents during the war, ten of whom were killed. These agents often worked behind enemy lines, donning Confederate uniforms or civilian clothing, and served as couriers between Sharpe and other agents.

In contrast, other Union intelligence efforts were often led by individual generals who took charge of intelligence gathering for their own operations. For example, General George B. McClellan hired Allan Pinkerton to set up the first Union espionage organization in mid-1861. Similarly, Lafayette C. Baker conducted intelligence and security work for Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army.

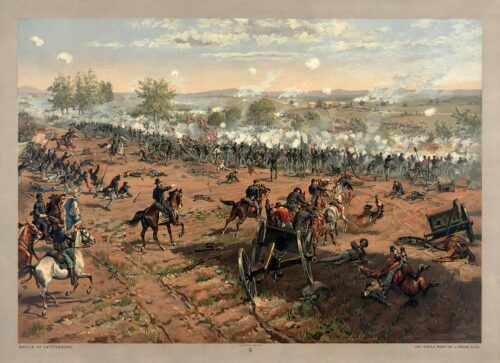

One notable contribution to the Union’s success in the Civil War came from an escaped enslaved man from the Army of Northern Virginia named Charley Wright. In June 1863, Wright observed an immense Confederate force under General Robert E. Lee passing through Culpeper, Virginia. Wright crossed into Union lines and shared with the BMI the precise units he observed and their destination. In response to Wright’s intelligence, General Hooker advanced his forces north to shadow Lee’s movement through the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia, and into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Without Wright’s timely and detailed intelligence, the Confederate Army could have threatened Washington, D.C. on its way north. Although the two armies were destined to meet regardless, there likely wouldn’t have been a Battle of Gettysburg without Wright’s intelligence contribution. This conflict resulted in a decisive victory for the Union Army and marked a turning point in the Civil War.

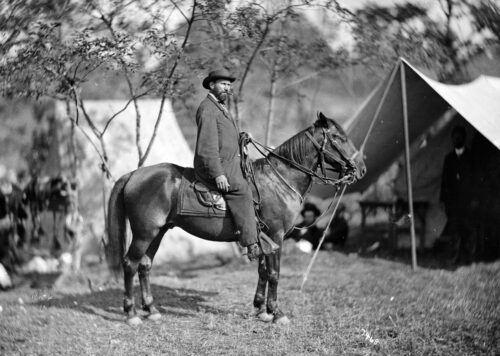

The BMI’s reports helped shape the decisions and actions of the Union commanders, such as Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. The BMI was a key factor in the Union’s victory in the Civil War, as it gave them an edge over the Confederate forces.

The BMI’s existence was short-lived as all operations were shut down at the end of the Civil War in 1865. However, its legacy lives on as it set a precedent for future military intelligence operations.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.