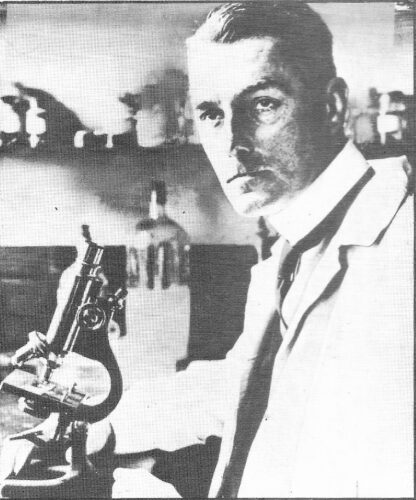

Charles Cholmondeley and Ewen Montagu, two of the British intelligence officers involved in the planning of Operation Mincemeat, shown in front of the vehicle transporting the body of Glyndwr Michael for pick up by submarine. Photo: Imperial War Museum.

Deception is a sort of seduction. In love and war, adultery and espionage, deceit can only succeed if the deceived party is willing, in some way, to be deceived.” ― Ben Macintyre, Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory.

Operation Mincemeat was one of the most successful deception operations of the Second World War. Based on a document from 1939, known as the Trout memo, used the analogy of fly fishing to explain how to deceive the enemy in wartime, it was officially attributed to Admiral John Godfrey, the Director of the British Naval Intelligence Division (NID), but some historians believe it was actually written by his assistant, Lieutenant Commander Ian Fleming, who later became famous for his James Bond spy novels. It certainly had all the hallmarks of Fleming. The Trout memo was a key influence on the Allied deception operations in World War II.

The Trout memo was written in 1939. The memo compared deception of an enemy in wartime with fly fishing and suggested 54 ways to fool or lure the Germans. One of these ideas, titled “A Suggestion (not a very nice one)”, was to plant fake documents on a dead body and make it look like a plane crash, which was inspired by a novel written by. Basil Thompson. This idea inspired Operation Mincemeat, a deception plan that misled the Germans about the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943.

Operation Mincemeat was developed by two other intelligence officers, Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley, who were part of the Twenty Committee, a group responsible for overseeing deception operations. Montagu was a lawyer and Royal Navy officer who played a leading role in devising and executing Operation Mincemeat, together with Cholmondeley, a Royal Air Force (RAF) officer and inventor.

The Twenty Committee was a covert British group that orchestrated the Double-Cross System, a counterespionage and deception operation that manipulated German spies in Britain during World War II. The committee derived its name from the Roman numeral for twenty, XX, which also signifies a double cross. The committee was headed by J. C. Masterman, an Oxford historian and international sportsman who had been recruited by MI5, the British Security Service. The committee’s main objective was to oversee the disinformation that the double agents transmitted to their German contacts, often deceiving them about Allied intentions and actions. The committee’s work was vital for the success of several Allied operations, such as Operation Mincemeat.

On 13 April 1943, the Chiefs of Staff committee approved the plan. They informed Colonel John Bevan, the head of the London Controlling Section that managed deception operations. Bevan explained the plan to the prime minister Winston Churchill, who was in bed with a cigar, in his Cabinet War offices. He told Churchill about the possible risks, such as the Spaniards returning the body and the papers to the British. Churchill said, “then we’ll have to take the body and make it swim again”. Churchill approved the operation, but left the final decision to Eisenhower, the military commander in charge of the Sicily invasion. Bevan sent a coded message to Eisenhower’s base in Algeria asking for confirmation, which he got on 17 April.

Montagu laid out three requirements for the letter that contained the fabricated plans. He insisted that the target should be referred to in an informal but unmistakable manner, that it should list Sicily and Sardinia as false alternatives, and that it should be in a private correspondence that would not normally be delivered by a diplomatic courier, or encrypted signal.

To find a suitable body and avoid detection by a Spanish doctor, Montagu consulted the pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury. Spilsbury told him that air crash victims often died of shock, not drowning, and their lungs might not have water in them. He also said that “Spaniards, being Roman Catholics, disliked post-mortems and only did them if the death was very important”. Spilsbury suggested that many possible causes of death could be mistaken in an autopsy.

Montagu later wrote “If a post mortem examination was made by someone who had formed the preconceived idea that the death was probably due to drowning there was little likelihood that the difference between this liquid, in lungs that had started to decompose, and seawater would be noticed.”

Montagu and Cholmondeley obtained the corpse of a homeless man named Glyndwr Michael, who was born in 1909 in Aberbargoed, Monmouthshire, and moved to the Rhondda valley with his family. He suffered from chronic illness and emotional instability and became destitute and lonely after his father’s death in 1925 and his mother’s death in 1940. He moved to London, where he died of poisoning in 1943 after eating rat poison.

The corpse was dressed as a Royal Marines officer with personal items identifying him as the fictitious Captain (Acting Major) William Martin. The “pocket lint” included a photo of his supposed fiancée, a bill for a diamond ring, and a ticket from a theater show. The naval identity card for Martin required a photo, but photographing the corpse proved unsuccessful, as it looked too dead in the pictures. Montagu and Cholmondeley searched for someone who resembled the dead man and found Captain Ronnie Reed of MI5. Reed agreed to pose as Martin in a Royal Marine uniform for the photo.

They also planted false documents in an official briefcase that would not be overlooked. To ensure the briefcase remained with the body, it was attached with a leather-covered chain, such as was used by bank and jewelry couriers to secure their cases against snatching. The documents included the letter with the fabricated plans indicating that the Allies were planning to attack Greece and Sardinia instead of Sicily. They were part of a wider deception strategy called Operation Barclay.

The body was sealed inside a canister with 21 pounds of dry ice to keep out oxygen and prevent decay. A MI5 driver, St John “Jock” Horsfall, who had been a racing champion before the war, drove the 1937 Fordson van with the canister. Cholmondeley and Montagu were in the back of the van. They went to Greenock, west Scotland, where the submarine HMS Seraph took the canister. Seraph’s commander, Lt. Bill Jewell, and crew had done special operations before. Jewell said told the crew the canister had a secret weather device for Spain.

Seraph left on 19 April 1943 and reached the coast of Huelva, near the south of Spain, on 29 April, despite being attacked twice on the way. The crew surveyed the shore during the day, then surfaced at 0415 (4:15 am) on 30 April. Jewell and his officers took the canister on deck and released the body into the sea. The body drifted for about an hour and a half before reaching the shore, where it was discovered by a local fisherman.

The Spanish authorities recovered the briefcase with the “secret” documents” but instead of turning them it over it the Germans as they were supposed to, refused to turn the briefcase over to anybody. Just as the British were beginning to fear that all was lost, a Nazi sympathizer within the Spanish Naval Authority secretly opened, photographed the documents and sent them to German intelligence in Spain. The Germans believed the false information and moved more troops to Sardinia, as well as Greece and the Balkans. The Allies invaded Sicily on 9 July 1943 and caught the German defenders off guard. The island was fully captured by the Allies in a month, and the lack of German reinforcements was a key factor in their victory. The Germans had fallen for ‘Mincemeat’.

Operation Mincemeat was one of the most successful deception operations of the war and was an inspiration for Fleming’s later novels. There have also been several books and films based on the true story. The details of Operation Mincemeat were kept secret for many years until they were declassified in the 1990s.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.