In the early morning hours of December 3, 1948, investigators from the House Un‑American Activities Committee (HUAC) arrived at a quiet farmhouse in Westminster, Maryland. They expected to collect evidence from Whittaker Chambers, a former Soviet courier who had recently accused a prominent State Department official of espionage. What they found instead was a hollowed pumpkin in the garden that contained rolls of microfilm. This unusual hiding place would soon become one of the most iconic symbols of Cold War suspicion and political conflict. The discovery helped lead to the conviction of Alger Hiss for perjury and shaped American debates about loyalty, secrecy, and the reach of Soviet intelligence.

Whittaker Chambers and the Origins of the Evidence

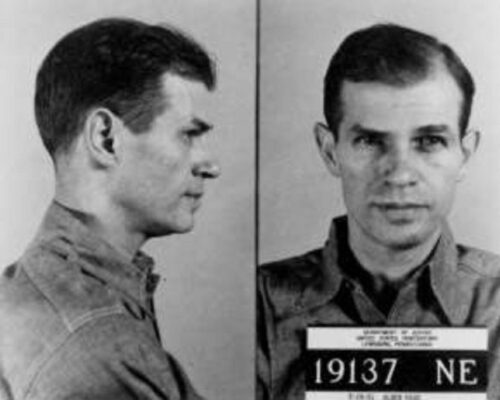

Whittaker Chambers had once been part of a covert Soviet underground network operating in Washington, D.C. During the 1930s he served as a courier who transported documents from sympathetic government employees to Soviet handlers. Chambers defected from the Communist movement in 1938 and later claimed that he feared retaliation from Soviet agents. For this reason, he kept a small collection of documents that he said had been passed to him by members of the network. Among those individuals, he alleged, was Alger Hiss, a rising figure in the State Department.

The materials Chambers preserved included typed copies of State Department documents, handwritten notes, and several rolls of microfilm. These items had been stored for years in an envelope held by a relative. Chambers retrieved them in late 1948 after his public dispute with Hiss intensified. The documents dated from early 1938 and included diplomatic cables, technical diagrams, and other government materials that were not intended for public release.

The Ware Group and Its Role in the Underground Network

Chambers also testified that several of the individuals he encountered in the underground had originally been part of the Ware Group, a secret circle of government employees and New Deal professionals organized in the early 1930s by economist Harold Ware. The group began as a Marxist study collective but, according to Chambers and later congressional investigators, some of its members were eventually recruited into a more clandestine apparatus that maintained contact with Soviet intelligence.

The Ware Group itself was not an espionage cell, but it served as a pool of potential recruits for those seeking sympathetic officials inside the federal government. Chambers stated that when he entered the underground, several former Ware Group members—including Alger Hiss and his brother Donald—were already involved in activities that went beyond political discussion. This connection became a key part of the narrative advanced by investigators: that the Hiss case was not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of covert influence within the New Deal bureaucracy.

The Discovery in the Pumpkin Patch

On December 2, 1948, HUAC investigators arrived at Chambers’s farm with a subpoena. Chambers believed that the documents might be seized or destroyed before Congress could examine them, so he hid the microfilm in a hollowed pumpkin in his garden. When investigators returned shortly after 2:00 a.m. on December 3, Chambers led them to the pumpkin patch. Inside the pumpkin they found the microfilm wrapped in wax paper.

Although the cache contained only film and not paper documents, the dramatic setting captured the imagination of the press. Reporters quickly labeled the material the “Pumpkin Papers,” and the name became permanently attached to the case. The discovery provided physical evidence that supported Chambers’s claim that he had once been part of a Soviet intelligence network that operated inside the U.S. government.

Alger Hiss and the Legal Battle

Alger Hiss was a respected diplomat who had served in the Roosevelt administration and played a role in the founding of the United Nations. The accusation that he had passed documents to the Soviets shocked Washington. Hiss denied knowing Chambers beyond casual social contact and insisted that he had never been involved in espionage. The Pumpkin Papers, however, strengthened Chambers’s credibility and raised serious questions about Hiss’s earlier testimony.

Because the statute of limitations for espionage had expired, Hiss could not be charged with spying. Instead, he was indicted for perjury. Prosecutors argued that he had lied under oath when he denied giving documents to Chambers and when he denied knowing him during the period in which the documents were created. The first trial ended without a verdict. A second trial in January 1950 resulted in Hiss’s conviction on two counts of perjury. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

The Impact of the Pumpkin Papers

The Pumpkin Papers played a central role in the government’s case. They demonstrated that someone within the State Department had provided Chambers with classified materials. Although the evidence did not conclusively prove that Hiss was the source, the combination of the microfilm, the typed documents, and the handwritten notes attributed to him created a powerful narrative that convinced the jury.

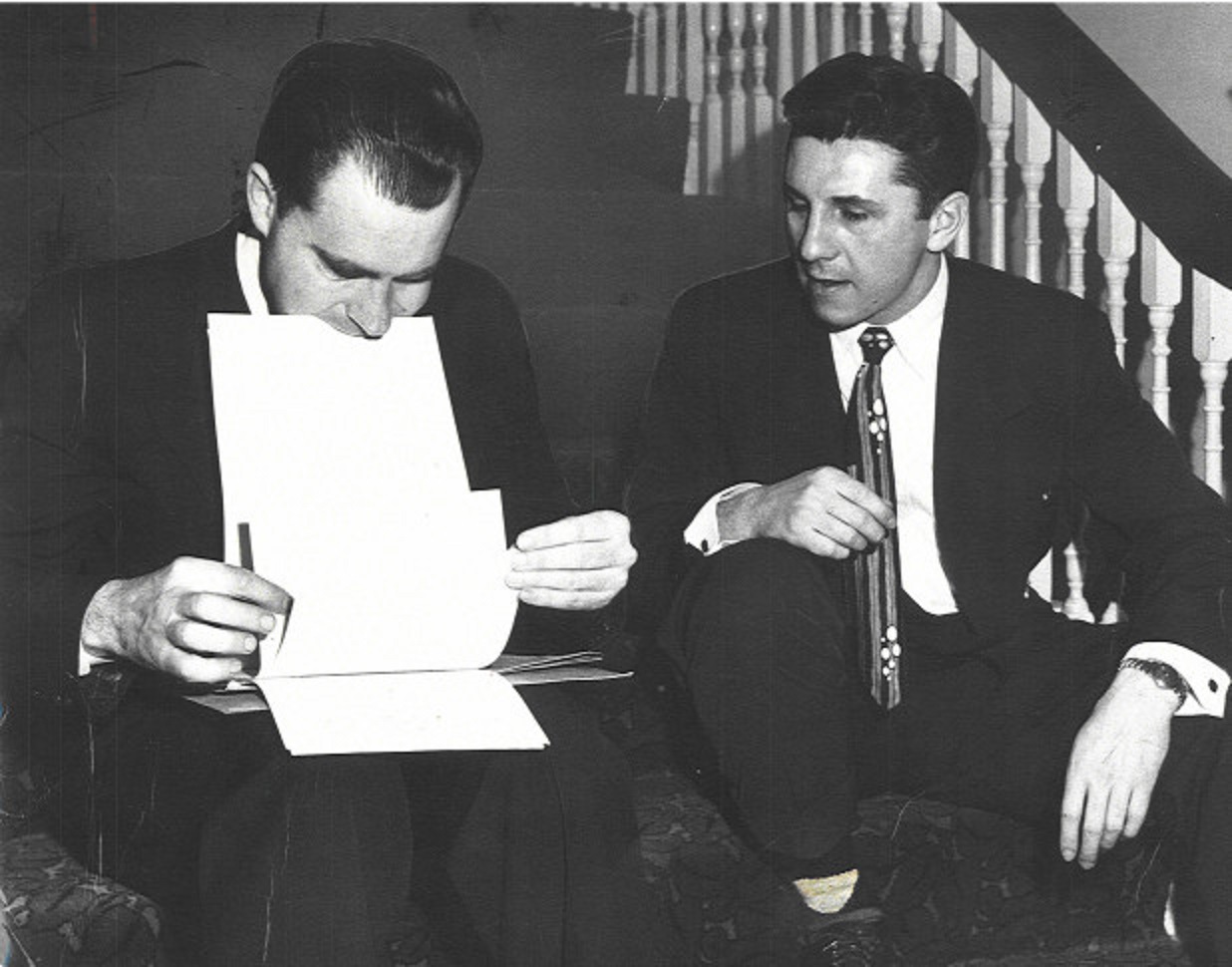

The case unfolded during a period of growing Cold War tension. The Soviet Union had recently tested its first atomic bomb, and Communist forces were gaining ground in China. Many Americans feared that Soviet agents had infiltrated the federal government. The Hiss case seemed to confirm those fears. It also helped elevate the political career of a young congressman from California, Richard Nixon, who played a key role in the investigation and gained national prominence as a result.

A Controversy That Endures

The Hiss case has remained one of the most debated episodes of the Cold War. Supporters of Hiss argued for decades that the evidence was unreliable or fabricated. Critics maintained that the documents, including the Pumpkin Papers, pointed strongly toward his involvement in Soviet intelligence. The release of Soviet archival material in the 1990s, including the Venona decrypts, provided additional support for the view that Hiss had been connected to Soviet espionage. Even so, the controversy has never been fully resolved in the public mind.

Supporters of the view that Alger Hiss was the Soviet source known as ALES point to several details in the Venona decrypts that appear to match his background and movements. A 1945 cable describes ALES as a high‑ranking State Department official who attended the Yalta Conference and then traveled to Moscow afterward, which aligns with Hiss’s documented itinerary. The cable also states that ALES had been cooperating with Soviet intelligence since the mid‑1930s, a period that corresponds to the years in which Whittaker Chambers claimed Hiss was involved in underground activity. In addition, ALES is described as having close ties to a small group of U.S. government officials who were already identified as part of a Soviet network. These overlapping biographical and contextual details form the core of the argument that Hiss was the individual referenced in the Venona messages.

What is clear is that the Pumpkin Papers had a lasting influence on American political culture. They intensified fears of internal subversion, contributed to the rise of McCarthyism, and deepened the ideological divisions that shaped the Cold War era. The image of microfilm hidden inside a pumpkin became a symbol of the period’s anxieties and a reminder of how espionage, politics, and personal reputation can collide in dramatic ways.

Cultural Echoes

The Pumpkin Papers even found their way into American film and popular culture. In Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), Cary Grant makes a playful reference to the case during the Mount Rushmore climax, telling Eve Marie Saint, “I see you’ve got the pumpkin,” as she retrieves microfilm hidden inside a statue. That same year, the Three Stooges short Commotion on the Ocean used a similar device, featuring microfilm concealed in a watermelon. Decades later, the 1982 documentary The Atomic Café incorporated archival footage of the FBI recovering the Pumpkin Papers, followed by a press briefing with Richard Nixon and HUAC investigator Robert Stripling. These appearances underscored how deeply the episode had entered the national imagination, becoming shorthand for Cold War secrecy and the era’s fascination with espionage.

Final Thoughts

The discovery of microfilm in a hollowed pumpkin on a Maryland farm remains one of the most memorable moments in American espionage history. The events of December 3, 1948, did more than expose a clandestine Soviet operation. They ended the career of a prominent diplomat, propelled a young congressman to national prominence, and helped define the political climate of the early Cold War. The Pumpkin Papers continue to serve as a powerful example of how a small cache of documents can alter the course of history.

On May 17, 1988, President Ronald Reagan designated the Whittaker Chambers Farm as a National Historic Landmark.