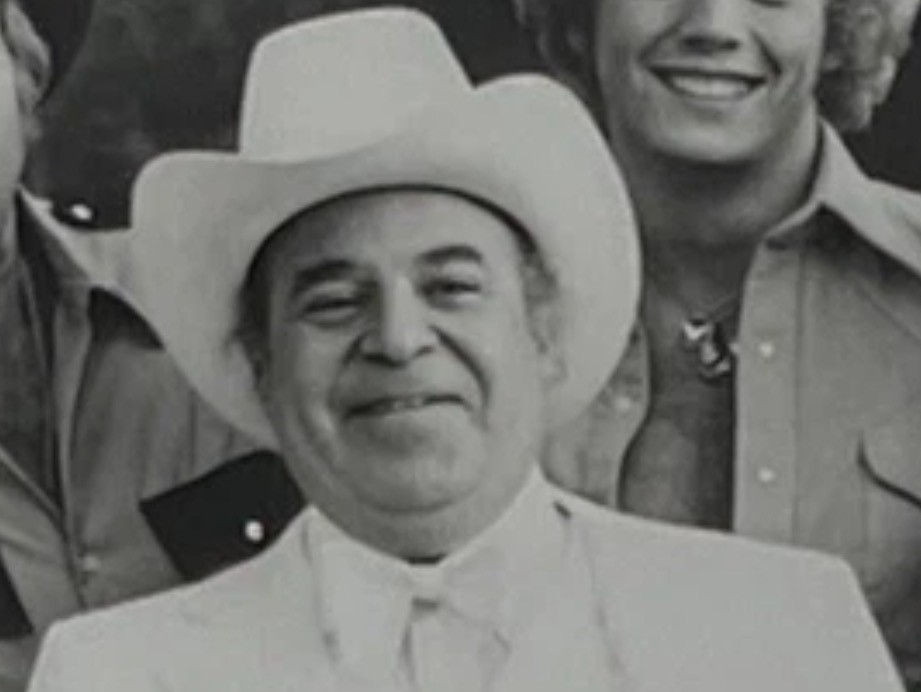

By the time Sorrell Booke waddled onto American television screens in a white suit and ten‑gallon hat, barking orders as the gleefully corrupt Boss Hogg, he had already lived a life far stranger, and far more dangerous, than anything in Hazzard County. His fans knew the actor. Almost no one knew the spy.

For decades, Booke’s pre‑Hollywood years remained a quiet footnote, overshadowed by his comedic brilliance. But behind the scenes, the man who played one of television’s most outrageous villains had once served in the shadows of the Korean War, working in military intelligence, psychological operations, and counterintelligence missions that still sit behind redacted lines in government archives.

This is the story of the role he never talked about. and the one he may have played best.

A Prodigy in Buffalo

Sorrell Booke was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1930, the son of hardworking parents who quickly realized their child was something of a prodigy. He devoured books, mastered languages, and graduated as valedictorian of his high school class. Columbia University accepted him early; he graduated magna cum laude before most of his peers had figured out their majors.

By his early twenties, Booke spoke five languages fluently. He could shift from French to Japanese to Russian with the ease of someone changing radio stations. It was a gift that would soon draw the attention of a very different kind of audience.

The War That Changed Everything

When the Korean War erupted in 1950, Booke was still a young scholar with dreams of the stage. But the U.S. Army had other plans. His linguistic skills and sharp analytical mind made him an ideal candidate for military intelligence, and he was quickly swept into the world of counterintelligence—an arena where secrecy wasn’t just expected, it was mandatory.

Inside the Intelligence Machine

Booke’s assignments placed him squarely in the heart of the Cold War’s first major conflict, where the Korean peninsula became a crucible for intelligence work. His duties were wide‑ranging and often perilous. He conducted interrogations of captured enemy personnel, helped shape psychological warfare strategies, analyzed intercepted communications, and participated in counterintelligence operations that frequently overlapped with early CIA activities in the region. These were not theoretical or administrative tasks. They were frontline intelligence missions carried out in an environment where the situation could shift by the hour.

Korea was a volatile battleground, a place where alliances were uncertain, information was scarce, and the wrong assumption could cost lives. Intelligence officers operated under constant pressure, navigating a landscape where loyalties blurred and the fog of war was ever‑present. In this setting, Booke’s mastery of multiple languages made him indispensable. He could extract nuance from conversations, interpret subtle cues in documents, and decode meaning from intercepted messages in ways few others could.

Much of his work remains classified, sealed behind government redactions that hint at the sensitivity of his assignments. Yet those who served alongside him offered glimpses of the man behind the secrecy. They described him as calm under pressure, perceptive in his judgments, and unflappable even in the most demanding situations. These qualities—honed in interrogation rooms and intelligence briefings—would later surface in his acting career, giving his performances a depth and steadiness that audiences felt even if they never knew the source.

The Silence of a Spy

Unlike many veterans, Booke rarely spoke about his service. He didn’t trade war stories at parties or use his military past to burnish his public image. He carried it quietly, the way intelligence officers are trained to do.

Friends later recalled that he had a way of listening, really listening, that felt almost surgical. He could read a room in seconds. He understood people. He understood motives. These were skills honed not in acting classes, but in interrogation rooms half a world away.

Returning to the Light

After the war, Booke resumed his studies at Yale, earning a Master of Fine Arts and stepping back into the world he had always loved: acting. He built a steady career on Broadway, in films, and on television. He played diplomats, doctors, gangsters, and professors. He could be funny, menacing, or heartbreakingly sincere. But nothing prepared him, or the world, for the role that would define him.

The Birth of Boss Hogg

In 1979, Booke was cast as Jefferson Davis “Boss” Hogg in The Dukes of Hazzard. The character was a cartoonish tyrant: greedy, corrupt, and perpetually scheming. Booke threw himself into the role with gusto, padding his body, perfecting the accent, and crafting a performance that was equal parts villainy and vaudeville.

Audiences adored him. Children imitated him. Critics praised his comedic timing. And yet, the contrast was staggering. The man who once conducted interrogations in the Korean War was now America’s favorite buffoonish bad guy. It was the ultimate transformation, one that only a deeply skilled, deeply disciplined performer could pull off.

A Legacy in Two Worlds

Sorrell Booke died in 1994, leaving behind a career that spanned stage, screen, and the secret corridors of Cold War intelligence. His life is a reminder that some of America’s most beloved entertainers once served their country in ways the public never fully knew.

Behind the laughter, behind the white Cadillac and the cigar-chomping bravado, was a man who had once navigated the dangerous, classified world of military intelligence. His greatest performance may not have been Boss Hogg at all, but the quiet, unseen role he played in history. A role he never bragged about. A role he never explained. A role he carried to the end.