Aerial photograph of the National Reconnaissance Office by Trevor Paglen. Commissioned by Creative Time Reports, 2013.

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) is a pivotal institution within the United States Intelligence Community. As an agency of the US Department of Defense (DoD), the NRO has a unique and critical mission.

The NRO is considered, along with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), National Security Agency (NSA), Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), to be one of the “big five” US intelligence agencies.

The NRO was founded in 1961, but its existence remained classified until 1992. It was established after management problems and insufficient progress with the US Air Force (USAF) satellite reconnaissance program. The NRO’s primary mission was, and still is, to develop, build, launch, and operate space reconnaissance systems and conduct intelligence-related activities for US national security.

Mission and Role

The NRO’s primary responsibility is to design, build, launch, and operate the reconnaissance satellites of the US federal government. These satellites serve as the nation’s eyes and ears in space, providing invaluable intelligence to several government agencies.

The NRO’s intelligence contributions are diverse, supplying signals intelligence (SIGINT) to the National Security Agency (NSA), imagery intelligence (IMINT) to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), and measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA).

The NRO is not just an intelligence agency; it’s also a hub of innovation. Since its establishment in 1961, the NRO has been at the forefront of satellite technology innovation. It works closely with both government and commercial partners to obtain innovative tools and technologies.

CORONA Program

The CORONA program was America’s first successful photo-reconnaissance satellite initiative. It was a highly classified effort jointly managed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the US Air Force. The program began in the late 1950s and was publicly known as a scientific research program named DISCOVERER

The CORONA satellites were used for photographic surveillance of the Soviet Union (USSR), China, and other areas beginning in June 1959 and ending in May 1972. The primary goal of the program was to develop a film-return photographic satellite to replace the U-2 spy plane in surveilling the Sino-Soviet Bloc, determining the disposition and speed of production of Soviet missiles and long-range bombers assets.

The CORONA program was pushed forward rapidly following the shooting down of a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union on 1 May 1960. The CORONA satellites captured incredibly valuable imagery while orbiting high above the Earth2, and the imagery played a crucial role in helping the U.S. understand the scope and success of Soviet efforts.

The first 13 missions of the CORONA program failed to return any usable imagery due to various technical issues. The program finally achieved success with CORONA Mission XIV on 18 August 1960. This mission returned from space more photographic coverage of the Soviet Union in a single mission than in all previous U-2 missions combined.

The NRO operated several different versions of CORONA during the program’s lifetime, introducing different camera systems and making incremental improvements. The earliest missions produced imagery with a ground resolution of 40 feet, using the KH-1 camera (KH denoted Keyhole, the name of the program’s security system).

POPPY Program.

The POPPY program was a continuation within the NRO’s Program C of the Naval Research Laboratory’s (NRL) Galactic Radiation and Background (GRAB)* electronic intelligence (ELINT) program, also known as Tattletale. The NRL proposed and developed POPPY in 1962 as an advanced successor to GRAB. Its primary mission was to collect radar emissions from Soviet naval vessels.

In 1962, the NRL, by then part of the NRO’s Program C, developed the larger and more advanced POPPY reconnaissance satellite. The first POPPY satellite was launched on December 13, 1962. The program successfully completed a total of seven missions. The last POPPY mission was launched on December 14, 1971.

POPPY missions supported a wide range of intelligence applications: Providing cues to the location of **Soviet radar sites; conducting ocean surveillance; and collaborating with photo-reconnaissance satellites to develop a comprehensive picture of the Soviet military threat.

These early spaceborne reconnaissance satellites — GRAB and POPPY —provided invaluable intelligence to U.S. policymakers. They laid the foundation for the NRO’s future signals intelligence satellite reconnaissance capabilities.

QUILL Program

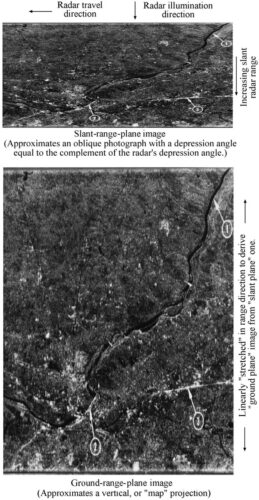

The QUILL program was an experimental Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellite initiative. Launched in 1964, QUILL aimed to validate the intelligence value of orbital SAR technology. It was based on the existing Corona satellite platform and utilized available SAR hardware.

QUILL imaged selected targets within the US. The primary goal was to demonstrate the capabilities of SAR without alerting the Soviets or causing diplomatic issues. By avoiding active illumination of sovereign territory, QUILL served as a proof-of-concept mission for orbital SAR technology.

The successful execution of the QUILL mission validated the feasibility of spaceborne SAR for intelligence purposes. It paved the way for future SAR-based reconnaissance satellites. The program contributed to the advancement of radar imaging capabilities and expanded the toolkit available for national security and intelligence gathering.

MOL Project.

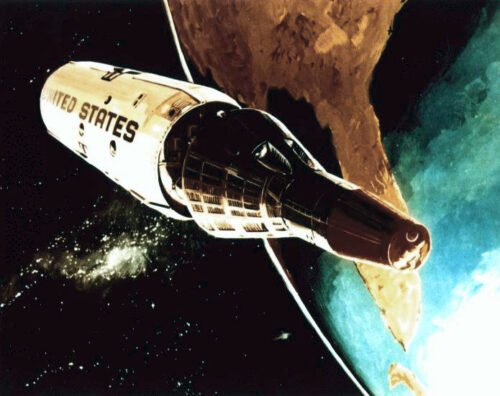

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program was an ambitious initiative launched by the NRO in 1965. Its primary goal was to test new abilities and fulfill a top-secret reconnaissance mission. The MOL aimed to provide rapid response intelligence collection from space.

The MOL envisioned a series of 60-foot-long space stations in low polar Earth orbit. Each station would be occupied by 2-man crews for 30-day missions at a time. Crews would launch and return to Earth aboard modified Gemini-B capsules.

The MOL program was announced to the public on December 10, 1963. While its reconnaissance satellite mission remained a secret black project, its purpose was to demonstrate the utility of putting people in space for military missions. Seventeen astronauts were selected for the program, including Major Robert H. Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut.

The prime contractor for the spacecraft was McDonnell Aircraft Corporation. The laboratory itself was built by the Douglas Aircraft Company. The Gemini B spacecraft, externally similar to NASA’s Gemini, underwent modifications for its role in the MOL program.

A single un-crewed test flight of the Gemini B spacecraft was conducted on November 3, 1966. Unfortunately, the MOL program was canceled in June 1969 without any crewed missions being flown. Seven of the MOL astronauts transferred to NASA in August 1969 as NASA Astronaut Group. These astronauts eventually flew in space on the Space Shuttle between 1981 and 1985.The MOL program also influenced other aspects of space exploration, including spacesuit development, waste management systems, and Earth science equipment.

The Future

In the 21st century, the NRO has continued to support current military operations, arms control, and other missions. It has also faced new requirements for information sharing and new approaches to secrecy. In 2023, the NRO announced ambitious plans for the following decade. It aims to quadruple the number of satellites it operates and increase the number of signals and images it delivers by a factor of ten.

The NRO plays a crucial role in America’s intelligence community. Its commitment to innovation and expansion underscores its importance in maintaining national security. As we look to the future, the NRO’s role will only become more vital as it continues to push the boundaries of space-based intelligence systems. Its intelligence vehicles are instrumental in keeping America safe and informed. The NRO’s efforts ensure that America remains the undisputed leader in space.

The US Space Force (USSF) and the NRO have established collaborative ties to advance space-based intelligence and targeting capabilities. Discussions continue on whether the USSF will field its own targeting satellites, rely on the NRO, or explore commercial industry options.

Resources

National Reconnaissance Office

NRO.gov

United States Space Force

SpaceForce.mil

Central Intelligence Agency

CIA.gov

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.