Few Cold War espionage stories are as compelling, or as improbable, as the Hollow Nickel Case. What began with a curious coin in Brooklyn in 1953 eventually led to the unraveling of a Soviet spy network and the arrest of one of the most notorious Soviet intelligence officers to ever operate on American soil: Rudolf Abel. This case not only captivated the public imagination but also reshaped U.S. counterintelligence operations during a tense era of global rivalry.

A Coin with a Secret

On June 22, 1953, 14-year-old newspaper delivery boy Jimmy Bozart was collecting his weekly payments in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. One customer handed him a nickel that felt unusually light. Later, Bozart accidentally dropped the coin on the ground, and to his surprise, it split open. Inside was a tiny piece of microfilm bearing a series of numbers, seemingly random and indecipherable.

Bozart turned the coin over to a local police officer, who in turn passed it to the FBI. Thus began what would become one of the most protracted and mysterious investigations in the Bureau’s history. The coin, dubbed the “hollow nickel,” was a classic example of a spy’s dead drop, a method of passing information without direct contact.

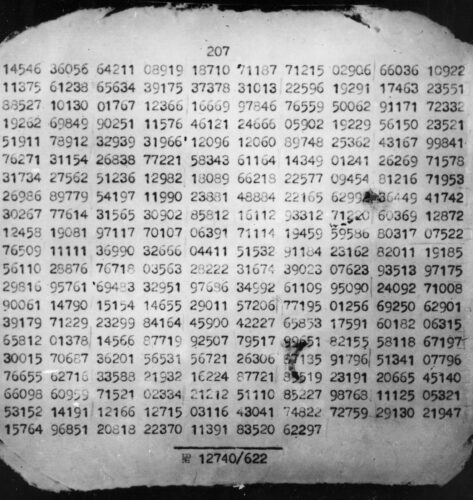

The microfilm inside the hollow nickel contained a series of numbers arranged in five-digit groups. Despite the FBI’s best efforts, the code remained unbroken for nearly four years. Without context, no known sender or recipient, the message was a cryptographic dead end. The FBI could not determine who had lost the coin, who was meant to receive it, or what the message said.

The case went cold, but the hollow nickel remained in FBI custody, a tantalizing clue to a puzzle that had yet to be solved.

A Defector Breaks the Case

The breakthrough came in May 1957, when a Soviet agent named Reino Häyhänen defected to the United States. Häyhänen had been operating under the alias Eugene Nicolai Mäki and was about to be recalled to Moscow, likely under suspicion. Fearing for his life, he approached U.S. authorities in Paris and offered to cooperate.

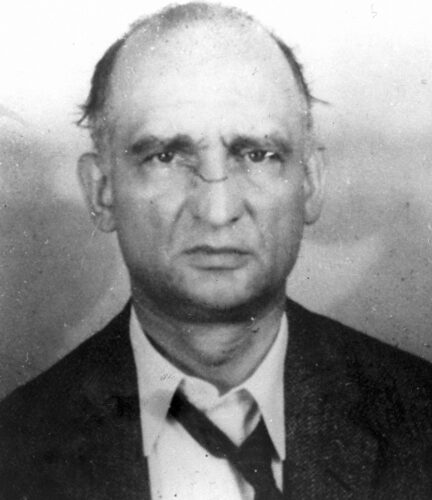

Häyhänen’s debriefing was a goldmine for the FBI. He revealed the existence of a Soviet spy network operating in the United States and identified his superior: a man living in Brooklyn under the name Emil Goldfus. This man was, in fact, William August Fisher, a Soviet intelligence officer of British birth, better known by his alias, Rudolf Ivanovich Abel. The alias Rudolf Abel was actually the name of a deceased Soviet agent. Fisher assumed it to signal to the KGB that he had been compromised. It was never his operational name in the U.S., but it became the name by which he was publicly known after his arrest.

He guided the FBI to a secluded “dead drop,” where agents recovered a hollowed‑out bolt containing a typewritten message. Questioned about it, Häyhänen explained that the Soviets had supplied him with an assortment of concealed containers—pens, screws, batteries, even coins. He handed over one of the coins, and agents immediately recognized its similarity to the mysterious Brooklyn nickel. The connection was unmistakable.

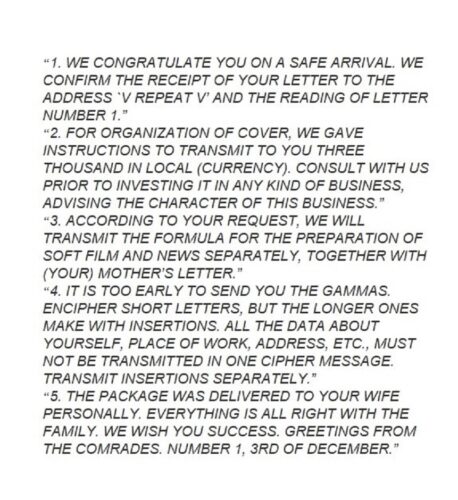

Häyhänen also provided the key to decrypting the message in the hollow nickel. It turned out to be a welcome message from Moscow to Häyhänen himself, sent shortly after his arrival in the U.S. in 1953. With this context, the FBI was finally able to decode the message and confirm the coin’s connection to Soviet espionage.

The Arrest and Conviction of Rudolf Abel

On June 21, 1957, the FBI arrested Abel at the Hotel Latham in Manhattan, where he had been staying under an assumed name. Abel was a seasoned intelligence officer who had been operating in the U.S. since the late 1940s. He used a variety of aliases, including Emil Goldfus and Martin Collins, and employed classic spycraft techniques: invisible ink, shortwave radio transmissions, and dead drops like the hollow nickel.

During a search of Abel’s studio in Brooklyn, agents found a trove of espionage tools, including hollowed-out bolts, cipher pads, and photographic equipment. The evidence was overwhelming.

Abel was charged with conspiracy to commit espionage and brought to trial in federal court in Brooklyn. His defense attorney, James B. Donovan, argued that Abel was entitled to a fair trial despite the political climate. Donovan’s principled defense would later earn him national respect and play a key role in future Cold War diplomacy.

In October 1957, Abel was convicted on all counts and sentenced to 30 years in prison. He was incarcerated at the Federal Correctional Institution in Atlanta, Georgia.

A Spy for a Spy: The Powers Exchange

Abel’s story didn’t end with his conviction. On May 1, 1960, American U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down over Soviet airspace during a high-altitude reconnaissance mission. His capture was a major embarrassment for the United States, exposing the extent of its aerial surveillance program. Powers was sentenced to ten years in a Soviet prison, sparking international tension and concern.

Behind the scenes, quiet negotiations began for a prisoner exchange. In February 1962, Abel was traded for Powers on the Glienicke Bridge in Berlin, a Cold War hotspot that would later earn the nickname “Bridge of Spies.” The exchange was orchestrated by James Donovan, Abel’s former defense attorney, who had earned the trust of both sides through his diplomatic skill and moral conviction.

The swap was a dramatic moment in Cold War history, symbolizing the high stakes, secrecy, and human costs of espionage. Abel returned to the Soviet Union, where he was welcomed as a hero and continued to work in intelligence circles. He died in Moscow in 1971; his legacy sealed as one of the most famous spies of the era. Powers, meanwhile, returned to the U.S. to a mixed reception, later writing a memoir and working in aviation safety until his death in 1977.

The Legacy of the Hollow Nickel Case

The Hollow Nickel Case remains one of the most iconic espionage cases in American history. It demonstrated the sophistication of Soviet intelligence operations and the challenges faced by U.S. counterintelligence during the Cold War. The case also highlighted the importance of seemingly minor details. A single coin led to the exposure of a major spy network.

The story has been retold in books, documentaries, and films, most notably in Steven Spielberg’s 2015 film Bridge of Spies, in which Tom Hanks portrayed James Donovan. While the film dramatized certain elements, it brought renewed attention to the real-life events and the individuals involved.

Final Thoughts

From a dropped nickel on a Brooklyn sidewalk to a dramatic spy swap on a bridge in Berlin, the Hollow Nickel Case is a testament to the unpredictable and often surreal nature of espionage. It’s a story of patience, luck, betrayal, and diplomacy woven into the broader tapestry of Cold War intrigue.

Though the Cold War has ended, the lessons of the Hollow Nickel Case endure in intelligence work, no detail is too small, and even the most ordinary objects can conceal extraordinary secrets.