Statue of Sun Tzu in Yurihama, Tottori, in Japan. Credit: 663highland / CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED. Cropped.

Foreknowledge cannot be gotten from ghosts and spirits, cannot be had by analogy, cannot be found out by calculation. It must be obtained from people, people who know the conditions of the enemy.” — Sun Tzu

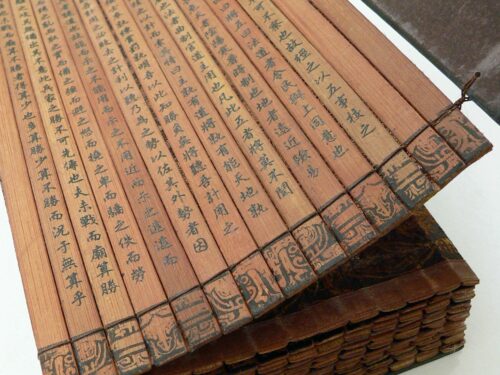

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is a timeless masterpiece that has been revered for centuries. This ancient Chinese military treatise, attributed to the military strategist Sun Tzu, offers profound wisdom on strategy, leadership, and human nature. Its teachings have transcended the battlefield, influencing various fields such as business, politics, and sports. The text’s enduring relevance stems from its deep understanding of conflict and its insights into how to achieve victory with the least amount of conflict. It remains a valuable guide for anyone seeking to navigate the complexities of strategy in any competitive environment. Chapter 13, titled “The Use of Spies”, is particularly relevant in the context of modern espionage.

The Essence of Chapter 13 – The Use of Spies

Sun Tzu begins the chapter by emphasizing the enormous financial, social, and human cost of war. He uses a symbolic vast sum of money to illustrate the financial burden of war. He also highlights the social and human impact, stating that war impedes the labor of as many as seven hundred thousand families.

Given these costs, Sun Tzu argues that it is economical to pay spies well to end the conflict sooner and return the men to their families. He asserts that remaining ignorant of the enemy’s condition because one grudges the outlay of a hundred ounces of silver in honors and emoluments is the height of inhumanity.

Sun Tzu identifies five types of spies: local, inward, converted, doomed, and surviving. Local spies are from the enemy state, while inward spies are officials in the enemy’s government. Converted spies are enemy spies who have been turned to the general’s side. Doomed spies pass on false information to the enemy, and surviving spies return with valuable information. The names of each of the five types of spies can differ with the translation. For example, doomed spy can be expendable spy or dead spy, depending on the translation.

Each type of spy has its own role and benefits in warfare, and their effective use can provide a strategic advantage. Please note that this is a simplified explanation and actual intelligence operations are far more complex and nuanced.

Sun Tzu suggests that only the virtuous can use spies effectively, referring to the Way, which confers political success on the morally righteous. This implies that the effective use of spies requires wisdom, humanity, and justice. Without these qualities, a general cannot verify the accuracy or truth of the information provided by the spies. He also emphasizes that no one should be closer to the general than his spies, nor better paid or treated.

Relevance to Modern Espionage

Chapter 13 of The Art of War provides a comprehensive guide on the use of spies in warfare. It underscores the importance of understanding the enemy’s condition and the value of investing in espionage to achieve this understanding. The chapter also highlights the different types of spies and the qualities required to manage them effectively.

In the grand scheme of warfare, Sun Tzu’s teachings in this chapter remind us that knowledge is power. The more a general knows about his enemy, the better prepared he is for battle. Thus, the use of spies becomes an essential strategy in warfare.

The principles outlined by Sun Tzu in The Art of War remain relevant to modern warfare and espionage. Intelligence gathering is a critical aspect of modern warfare, and the types of spies Sun Tzu identified can be seen in today’s intelligence agencies.

For example, In the context of modern espionage, converted spies could be seen in the practice of “double agents”. A double agent is a person who engages in clandestine activities for two intelligence or security services (or more in joint operations), who provides information about one or about each to the other, and who wittingly with forethought manipulates the two against each other.

Oleg Gordievsky is a good example. During the Cold War, Gordievsky was a high-ranking KGB officer who was turned by the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS/MI6). He provided the British with valuable information about Soviet intelligence operations for over a decade, while still appearing to serve the KGB.

It’s important to note that the use of converted spies or double agents is a high-risk strategy, as the possibility of counterespionage (the spy reverting to their original allegiance) is always present. This aligns with Sun Tzu’s assertion that managing spies and conducting espionage is a matter of supreme importance to the state.

Another example. In Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, “doomed spies” are used to pass on false information to the enemy. In modern times, this could be seen in the practice of disinformation or deception operations. However, specific examples of such operations are often classified and not publicly disclosed.

One historical example of a similar concept is Operation Mincemeat during World War II, where the British intelligence used a dead body to carry false information to deceive the Germans about the invasion of Sicily. The body was dressed as a British military officer and carried false invasion plans, which were subsequently discovered by the Germans.

Moreover, Sun Tzu’s emphasis on the moral righteousness of those who handle spies resonates with the ethical considerations that modern intelligence agencies must navigate. The use of spies involves a delicate balance of ethical dilemmas, and those in charge must have a strong moral compass.

Modern-day espionage has become more complex and challenging due to the advancements in technology and the vast amount of data available. It’s not just about gathering information anymore, but also about how to use that information effectively and ethically in a rapidly changing world. it has become more of a “cat-and-mouse” game between intelligence services and hostile agents, fought against the backdrop of big data. Agents continue to gather intelligence from three age-old sources: human interactions, signals, and imagery surveillance.

In the past, espionage activity was typically directed towards obtaining political and military intelligence. These targets remain of critical importance but in today’s technology-driven world, the intelligence requirements of a number of countries are wider than before.

Espionage is being transformed by cyber technology. Cyber space simultaneously makes offensive information gathering more valuable and cyber defense protections more necessary because of the sheer volume of data now available.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has a significant impact on cyber espionage. Attackers are already using AI as a weapon to refine phishing messages and improve influence operations with synthetic imagery. AI is also crucial for successful defense, automating, and augmenting aspects of cybersecurity such as threat detection, response, analysis, and prediction. The state of advancement in AI is doubling every six to 10 months.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the landscape of warfare and espionage has evolved over the centuries, the strategic insights from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War remain relevant. The principles outlined in Chapter 13 — The Use of Spies provide valuable lessons for intelligence gathering and spy handling in the context of modern espionage.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.