James Bond emerged at a moment when Britain was redefining itself after the devastation of World War Two. Ian Fleming, drawing heavily on his own experiences in Naval Intelligence, created a character who embodied both the harsh realities of wartime espionage and the escapist fantasies of a nation grappling with diminished global power. Bond became Fleming’s vehicle for expressing his beliefs about duty, masculinity, national pride, and Britain’s place in the rapidly changing postwar world. Through Bond, Fleming offered readers a figure who could navigate danger with confidence, uphold British values, and project an image of strength at a time when the country was struggling to maintain its influence.

Fleming’s Intelligence Career and Its Direct Influence on Bond

Fleming’s wartime service in the Naval Intelligence Division shaped nearly every aspect of the Bond novels. As assistant to Admiral John Godfrey, Fleming worked at the center of British intelligence planning, where he observed the inner workings of espionage at the highest levels. He helped design covert operations, coordinated with Allied agencies, and witnessed the psychological strain placed on operatives who lived in constant uncertainty. Although he was not a field agent himself, he had a front‑row seat to the strategies, personalities, and dangers that defined real intelligence work.

These experiences informed Bond’s procedural knowledge, his calm under pressure, and the bureaucratic structures surrounding MI6. Fleming’s familiarity with intelligence culture allowed him to portray the rhythms of espionage with unusual authenticity. Many of Bond’s missions echo real operations Fleming helped conceptualize or observed during the war, blending factual detail with dramatic embellishment. This mixture of realism and invention gave the novels a sense of credibility that distinguished them from other adventure fiction of the era.

Postwar Britain and the Crisis of National Identity

When Fleming began writing in the early 1950s, Britain was facing economic hardship, the rapid loss of empire, and a reduced role on the world stage. The Bond novels reflect Fleming’s desire to project an image of Britain as still powerful, decisive, and globally influential. Through Bond, Fleming imagined a nation whose intelligence services remained capable of shaping international events, even as Britain’s political and military dominance waned.

For many readers, this was a comforting fantasy during a period of national uncertainty. Bond’s competence, authority, and international reach symbolized the Britain Fleming wished to preserve: a Britain defined by elite institutions, moral clarity, and a sense of global responsibility. In this way, Bond became not only a fictional spy but also a cultural reassurance, embodying the idea that Britain still mattered in a world increasingly dominated by the United States and the Soviet Union.

Cold War Politics and the Shaping of Bond’s Enemies

The Cold War provided the geopolitical backdrop for Bond’s adventures and shaped the nature of his adversaries. Fleming’s early villains, particularly those associated with SMERSH, were drawn from real Soviet intelligence organizations he encountered during the war. These antagonists embodied Western fears of communist expansion, ideological infiltration, and the shadowy tactics of Soviet espionage. Fleming used them to dramatize the ideological struggle between East and West, giving readers a clear sense of the stakes involved.

As the Cold War evolved and political realities shifted, Fleming moved away from explicitly Soviet enemies and introduced SPECTRE, a non‑state criminal syndicate. This shift allowed him to maintain high‑stakes conflict without tying the stories too closely to real-world diplomacy or risking the novels becoming outdated. The creation of SPECTRE gave Fleming the freedom to explore global threats that were both contemporary and timeless, ensuring that Bond’s world remained flexible, dramatic, and relevant.

Fleming’s Personal Worldview

Fleming’s upbringing, education, and personal tastes shaped Bond’s character as much as his intelligence experience did. He admired refinement, exclusivity, and precision—values reflected in Bond’s love of fine food, tailored clothing, luxury brands, and meticulous routines. These cultivated preferences were not incidental; they echoed Fleming’s own lifestyle and mirrored the rise of postwar consumer culture, when modernity, style, and material sophistication became markers of identity and national pride. In Bond, Fleming projected the elegance he prized and the aspirational Britain he wished to see.

Bond’s masculinity also reflects Fleming’s ideals; drawn from the elite commandos and operatives he encountered during the war. Bond is self‑controlled, physically capable, emotionally restrained, and sexually assertive qualities that embodied both the virtues Fleming respected and the fantasies he indulged. Yet the literary Bond is not simply a wish‑fulfillment figure. His stoic discipline often clashes with his emotional detachment demanded by his work, exposing the strain of a man shaped by violence, duty, and isolation. These tensions reflect not only Fleming’s own contradictions but also the broader uncertainties of postwar masculinity and Britain’s shifting role in the world

Real Spycraft Blended with Romanticized Fantasy

Although Fleming grounded Bond in real intelligence procedures, he also infused the novels with glamour, spectacle, and heightened adventure. Fleming often described Bond as a blunt instrument of the state, yet he also acknowledged that Bond represented a romanticized version of the operatives he knew. The novels combine authentic details, such as surveillance techniques, bureaucratic rivalries, and the psychological toll of espionage, with exotic locations, dramatic confrontations, and larger‑than‑life villains.

This blend of realism and fantasy helped define the modern spy thriller. Fleming’s ability to merge procedural accuracy with imaginative storytelling set Bond apart from more strictly realistic espionage fiction. Readers were drawn to a world that felt both credible and thrilling, grounded in real intelligence culture yet elevated by adventure and escapism.

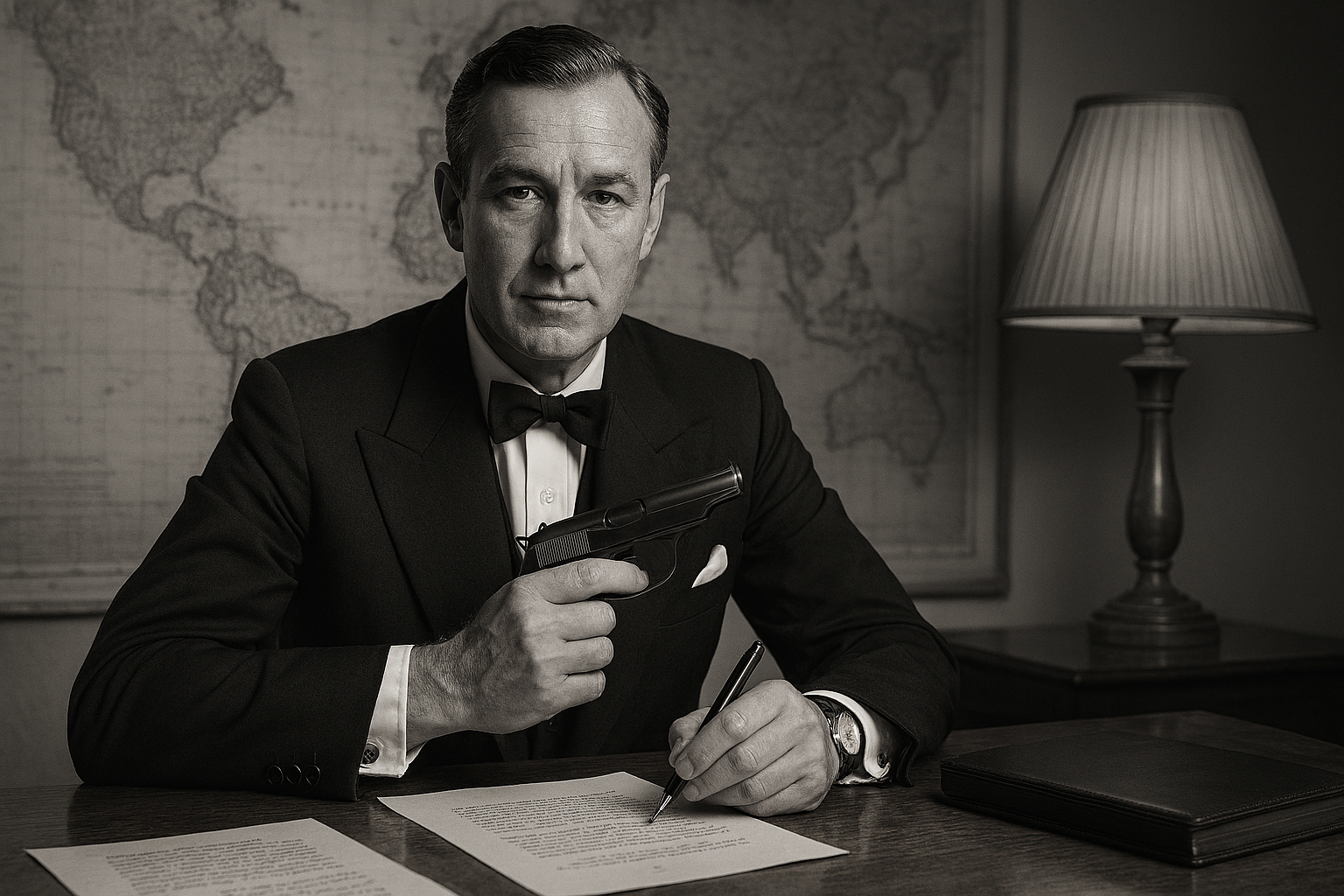

Fleming’s Bond vs. the Cinematic Bond

The James Bond of Ian Fleming’s novels and the James Bond who appears on screen share a name, a profession, and a certain cool competence, but they are ultimately two different creations shaped by different eras, audiences, and artistic priorities. Fleming’s Bond is leaner, colder, and far more introspective. On the page, Bond is a professional killer who often reflects on the moral weight of his work, the toll of violence, and the bureaucratic frustrations of serving the British state. He drinks and smokes too much, suffers from exhaustion and doubt, and operates with a sense of fatalism. Fleming’s Bond is not a superhero; he is a government instrument who survives through training, instinct, and a willingness to do unpleasant things in the name of duty.

The cinematic Bond, by contrast, evolved into a larger‑than‑life figure shaped by spectacle, charisma, and the demands of global entertainment. While early films with Sean Connery retained some of Fleming’s grit, the franchise quickly embraced a more glamorous, humorous, and physically invincible version of the character. Gadgets, elaborate stunts, and heightened villains became hallmarks of the film series, often overshadowing the quieter realism of the novels. Later portrayals, such as Daniel Craig’s, brought back elements of Fleming’s psychological depth and vulnerability, but even these versions operate in a world of blockbuster scale and stylized action. In essence, Fleming’s Bond is a spy shaped by postwar anxieties and personal demons, while the film Bond is a cultural icon engineered for mass appeal, cinematic fantasy, and evolving audience expectations.

Final Thoughts

James Bond is inseparable from Ian Fleming’s wartime experiences and personal worldview. The novels reflect the anxieties of the Cold War, the legacy of World War Two intelligence operations, and Britain’s struggle to maintain relevance in a rapidly changing world. Bond’s enduring appeal lies in this fusion of historical reality and imaginative projection. He is both a product of his time and a timeless symbol of competence, adventure, and national identity. Through Bond, Fleming preserved not only the world he knew but also the world he wished still existed, offering readers a hero who could navigate danger with elegance and uphold values that felt increasingly fragile.

Resources