Aerial view of the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters, Langley, Virginia.

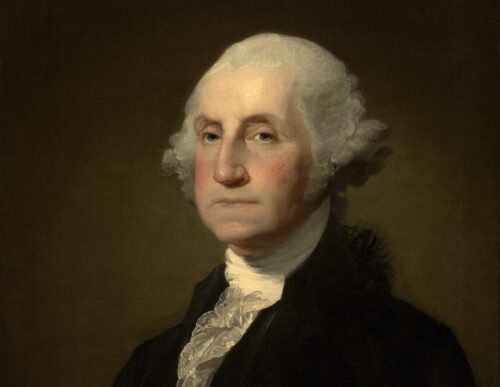

There is nothing more necessary than good intelligence to frustrate a designing enemy, and nothing requires greater pains to obtain.” — George Washington

The field of intelligence collection in America has seen a remarkable evolution. From its military-focused origins, intelligence operations expanded into civilian sectors reflecting the changing needs of the nation. This article explores the evolution of intelligence collection from in America from the Continental Congress to the modern era, highlighting key developments and shifts in strategy that have shaped the intelligence community (IC) as we know it today.

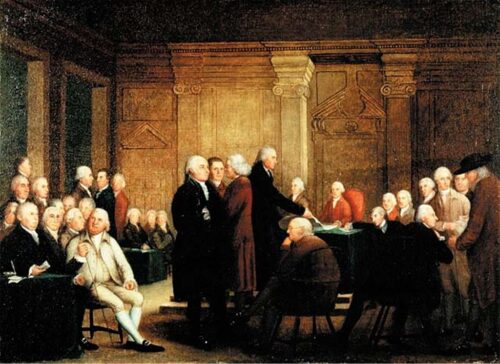

The Committee of Secret Correspondence

The Committee of Secret Correspondence was a committee formed by the Second Continental Congress and was active from 1775 to 1776. The Committee played a significant role in attracting French aid and alliance during the American Revolution. In 1777, the Committee of Secret Correspondence was renamed the Committee of Foreign Affairs.

With the American Revolutionary War approaching, the Second Continental Congress, which took place in Philadelphia in 1775, recognized the need for international allies to help the Thirteen Colonies in their fight for independence from Great Britain. To satisfy this need, the Congress created the Committee of Secret Correspondence.

The Committee of Secret Correspondence was created for “the sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain and other parts of the world”. However, most of the efforts of the committee went not to making friends in Great Britain, but towards forging alliances with other foreign countries that would sympathize with the patriot cause during the American Revolution.

While forming foreign alliances, the committee also employed secret agents abroad to gain foreign intelligence, conducted undercover operations, started American propaganda campaigns to gain patriot support, analyzed foreign publications to gain additional foreign intelligence, and developed a maritime unit separate from the Navy. It also served as the “clearinghouse” for foreign communications with foreign countries.

The Committee of Secret Correspondence was a crucial part of the intelligence operations during the Revolutionary War. Its creation marked the beginning of organized intelligence operations in the United States, laying the groundwork for future intelligence agencies.

The Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War, intelligence operations were primarily focused on military objectives. The war marked the birth of American intelligence, with George Washington, the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, recognizing the importance of collecting information about the enemy. He was a skilled manager of intelligence, utilizing agents behind enemy lines, recruiting both Tory and Patriot sources, interrogating travelers for intelligence information, and launching scores of agents on both intelligence and counterintelligence missions. Washington is often referred to as America’s first spymaster.

After experiencing several intelligence setbacks, including the capture and execution of Nathan Hale, George Washington became convinced of the critical importance of well-structured intelligence. George Washington’s spy network, known as the Culper Ring, was a crucial part of the American Revolutionary War. This network was organized by Major Benjamin Tallmadge and General George Washington in 1778 during the British occupation of New York City. The name “Culper” was suggested by George Washington himself and was taken from Culpeper County, Virginia. The Culper Ring was tasked with providing Washington with information on British Army operations in New York City, the British headquarters. Washington devoted nearly one-quarter of his limited budget for espionage to the Culper Ring. This secret intelligence network helped Washington make bold, canny decisions that would turn the tide of the conflict—and in some instances, even save his life.

The Mersereau Ring was another spy network that operated throughout the New Brunswick and New York regions during the American Revolution. It began gathering intelligence on British military activity for General George Washington as early as December 1776. The ring was set up by businessman and patriot Joshua Mersereau By 1777, the Mersereau Ring expanded into a greater intelligence network operating under Colonel Elias Dayton of the 1st New Jersey Militia.

The Dayton Spy Ring was established by American Colonel Elias Dayton early in 1777. It was set up on Staten Island and worked in conjunction with the Mersereau Ring. This spy network played a crucial role in gathering intelligence during the American Revolutionary War. The information collected by the Dayton Spy Ring, along with other networks, significantly contributed to the strategic planning and operations of the American forces

It is interesting to note, George Washington, was even known to have used invisible ink during the American Revolution. He financed a secret laboratory for the production of invisible ink in Fishkill, New York. This lab was managed by James Jay, the brother of Founding Father John Jay. The invisible ink was used by many of Washington’s spies, including the Culper Spy Ring of Major Benjamin Tallmadge and the Dayton Spy Ring of Col. Elias Dayton of Elizabeth, New Jersey.

The Early Republic

The end of the war saw a significant shift in intelligence operations. While military intelligence remained crucial, the focus expanded into civilian sectors. This expansion reflected the changing needs of the nation, with the realization that threats to national security could come from both military and civilian sources.

In the early years of the Republic, intelligence played a key role in supporting United States military forces and shaping United States policies toward other countries. While the function of intelligence as an activity of the United States government is often regarded as a product of the Cold War, intelligence has been a function of the government since the founding of the Republic.

The 19th Century

The 19th century saw further changes in intelligence collection with the advent of railroads and the development of general staffs for centralized planning. These developments created both a target for intelligence collection and an organizational home for the information gathered.

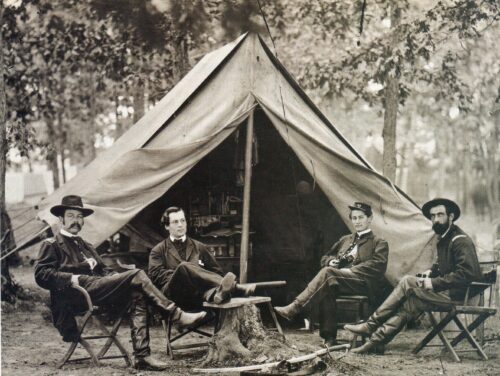

During the American Civil War, both the Union and the Confederacy recognized the importance of intelligence collection. The Union, for instance, utilized a variety of information sources, including scouts, spies, cavalry reconnaissance, Signal Corps observation and message interception, and even aerial scouting from balloons. They also analyzed Southern newspaper accounts and reports from other Union military commands.

Allan Pinkerton, the founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, played a significant role as a spy during the American Civil War. He was appointed as the head of the Union Intelligence Service, which was the first secret service in America. Operating under the pseudonym Major E. J. Allen, Pinkerton set up spy rings behind enemy lines and infiltrated southern sympathizer groups in the North.

Lafayette C. Baker was an investigator and spy, also serving for the Union Army, during the American Civil War and under Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. During the early months of the Civil War, he spied for General Winfield Scott on Confederate forces in Virginia. Despite numerous scrapes, he returned to Washington, D.C., with information that Scott evidently thought valuable enough to raise him to the rank of captain.

When Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War, heard about Baker, he recruited him as his replacement for Allan Pinkerton, head of the Union Intelligence Service. Baker was given the job as head of the National Detective Police (NDP), an undercover, anti-subversive, spy organization.

Union Intelligence Service headed by Pinkerton was itself replaced by the Bureau of Military Information (BMI) in January 1863. The BMI was the first formal and organized American intelligence agency, active during the American Civil War. It was established by Union Army Major General Joseph Hooker, who ordered Colonel George Sharpe to create a formal intelligence service.

The BMI collected information from a variety of sources, including Confederate deserters and prisoners, captured documents, and Southern newspapers. This information was then combined with data from other sources, such as reconnaissance balloons, intercepted telegraph messages, flag signals, and other Union cavalry units, to create a comprehensive intelligence picture.

The BMI was a significant development in wartime espionage operations. It was a more structured military intelligence organization than those of rival detectives Allan Pinkerton and Lafayette Baker. It set the stage for the evolution of intelligence collection in the years to come.

The Confederacy, on the other hand, set up a spy network in the federal capital of Washington, D.C., which was home to many Southern sympathizers. They also established the Confederate Signal Corps, which included a covert intelligence agency known as the Secret Service Bureau. This agency managed spying operations along the so-called “Secret Line” from Washington to Richmond.

The BMI was disbanded in 1865 at the end of the Civil War, after assisting General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox and playing a pivotal role in the paroling of Confederate General, Robert E. Lee. The United States would not create another formal intelligence agency until the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) was established in 1882.

The Civil War marked a significant shift in intelligence collection, with both sides employing sophisticated methods and creating dedicated organizations for this purpose. This period laid the groundwork for the modern intelligence community and the practices used today.

The 20th Century

In the 20th century, prior to the formation of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), American intelligence underwent significant changes and developments. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), often referred to as the forerunner of the CIA, became the first centralized intelligence agency in American history. Led by Major General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the OSS was tasked with collecting and analyzing strategic information and conducting unconventional and paramilitary operations.

Before World War II, intelligence collection was conducted by various departments such as the Department of State, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the United States Armed Services, with no direction or coordination. However, the need for a coordinated approach became apparent during the war. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) in 1941. The COI’s main goal was to gather foreign intelligence related to the war.

As World War II progressed, the COI was transformed into the OSS. At its peak, the OSS employed over 13,000 military personnel and civilians. Although the OSS existed for just over three years, it made a lasting contribution to the country and the future of American intelligence.

After World War II, President Harry S. Truman abolished the OSS, leaving the nation without a non-departmental, strategically oriented intelligence service. In response, branches of the OSS merged into a new office, the Strategic Services Unit (SSU). The SSU filled former OSS posts across the globe until a more permanent solution could be put in place.

In 1946, the duties and responsibilities of the SSU were moved to the newly created Central Intelligence Group (CIG). Unlike previous organizations of its kind, the CIG was granted the authority to conduct independent research and analysis. This marked a significant step towards the formation of the CIA in 1947.

The Central Intelligence Agency

The CIA is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States. It is officially tasked with gathering, processing, and analyzing national security information from around the world, primarily through the use of human intelligence (HUMINT) and conducting covert action through its Directorate of Operations.

The CIA was established as an independent, civilian intelligence agency within the executive branch by the National Security Act of 1947. This Act charged the CIA with coordinating the nation’s intelligence activities and, among other duties, collecting, evaluating, and disseminating intelligence affecting national security.

The CIA Act of 1949, also known as Public Law 110, permitted the CIA to use confidential fiscal and administrative procedures and exempted it from many of the usual limitations on the use of federal funds.

It is important to note that the CIA has no law enforcement function and is mainly focused on overseas intelligence gathering, with only limited domestic intelligence collection. Any domestic intelligence collection activities are coordinated with other agencies of the United States as appropriate.

The Intelligence Community Today

These changes laid the foundation for the modern IC, where civilian observation and mobilization considerations are as important as a military strategy. This evolution of intelligence collection reflects the changing needs and complexities of national security over time. The evolution of intelligence collection from the Second Continental Congress to modern times illustrates the adaptability and resilience of the IC in responding to the changing needs of national security. Intelligence collection continues to evolve.

The IC today consists of a group of separate United States government intelligence agencies and subordinate organizations that work both separately and collectively to conduct intelligence activities which support the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States The IC is overseen by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), which is headed by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) who reports directly to the President of the United States.

The IC is currently composed of the following 18 organizations:

- Two independent agencies—the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

- Nine Department of Defense (DoD) elements—the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the National Security Agency (NSA), the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), and intelligence elements of the five DoD services; the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Space Force.

- Seven elements of other departments and agencies—the Department of Energy’s Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence; the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis and United States Coast Guard Intelligence; the Department of Justice’s Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Office of National Security Intelligence; the Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research; and the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis.

Each of these agencies has a specific role and responsibility in the collection, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence to support the United States’ foreign policy and national security interests. They work both individually and collectively to ensure the safety and security of the nation.

Resource

Central Intelligence Agency

CIA.gov

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.