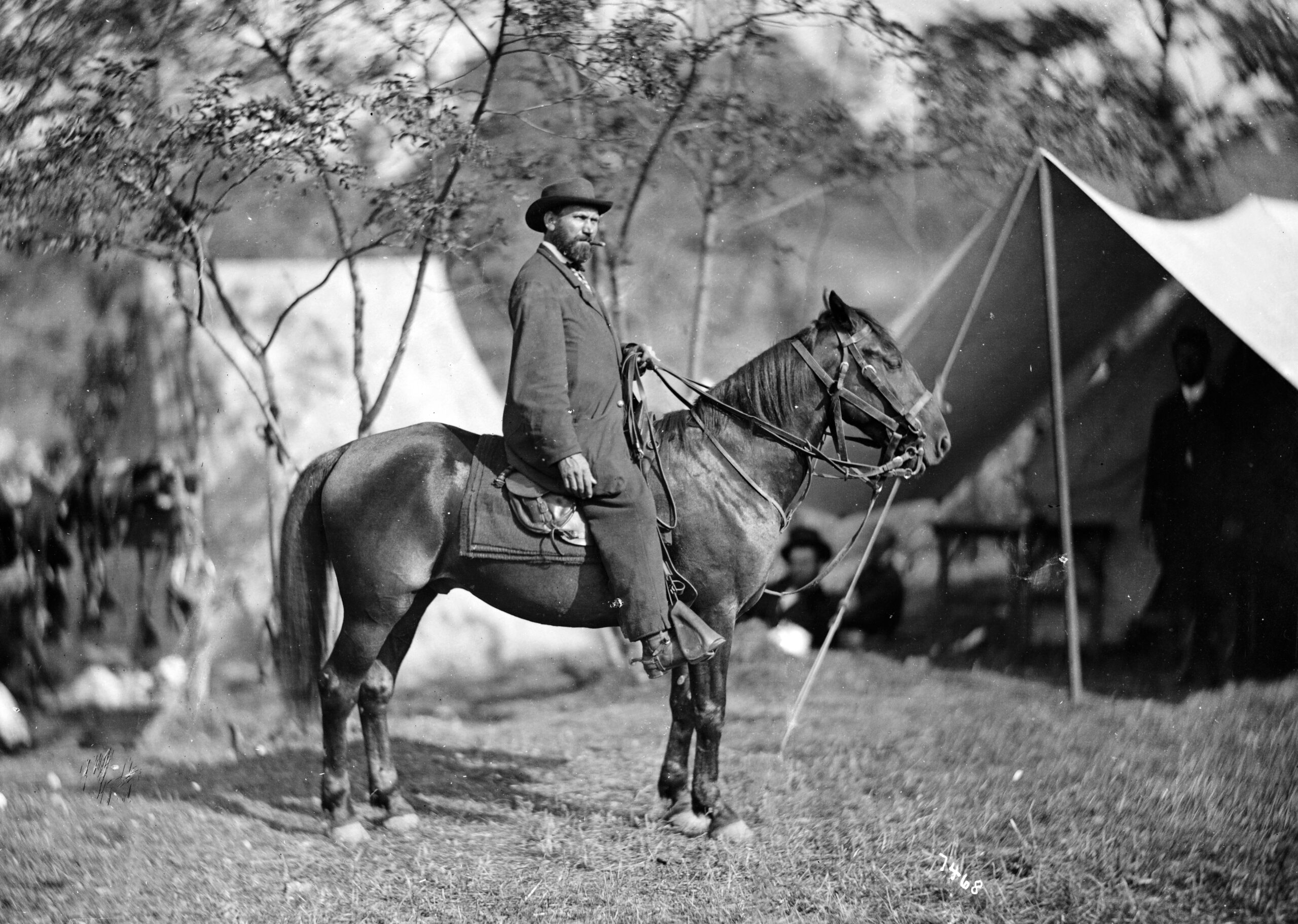

Alan Pinkerton on horseback on the Antietam Battlefield in 1862. Alexander Gardner – U.S, Library of Congress.

Alan Pinkerton was a Scottish-American detective and spy who founded the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in 1850. He was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on July 21, 1819, and grew up in poverty after his father’s death. He became a cooper and a political activist, supporting the Chartist movement for democratic reforms. He fled to the United States in 1842 to avoid arrest for his involvement in a strike.

Private Detective.

Pinkerton settled in Dundee, Illinois, where he started a cooperage and joined the abolitionist cause. He also became interested in detective work when he discovered a gang of counterfeiters and helped the sheriff arrest them. In 1849, he was appointed as the first police detective in Chicago, and a year later, he formed his own detective agency with lawyer Edward Rucker. The agency’s motto was “We never sleep” and its logo was an eye. The logo is the origin of the term “private eye” for private detectives.

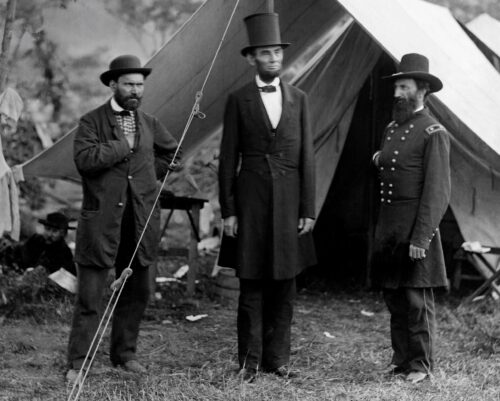

He and his agents foiled an assassination plot, known as the Baltimore Plot, against President-elect Abraham Lincoln in late February 1861. Lincoln was supposed to travel through Baltimore, Maryland, where he had very little support and faced a hostile crowd. Pinkerton was hired by the railroad company to protect Lincoln from any possible threats along his route.

The Baltimore Plot was a conspiracy by some pro-slavery extremists to assassinate Lincoln when he passed through Baltimore, Maryland, a city with strong secessionist sentiments. Pinkerton and his agents uncovered the plot and warned Lincoln of the danger. They devised a plan to secretly change Lincoln’s itinerary and disguise him as an invalid to avoid detection. Lincoln agreed to follow Pinkerton’s advice and arrived safely in Washington, DC, on February 23, 1861

Civil War Spy.

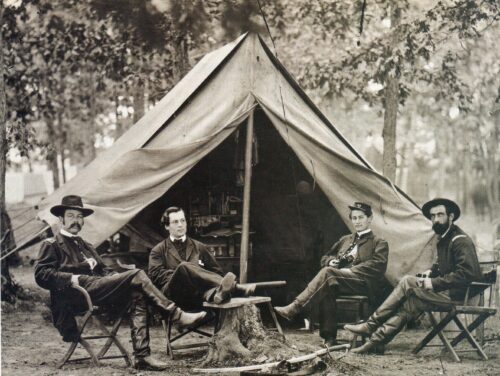

Pinkerton gained fame for his role as the head of the Union Intelligence Service during the first two years of the Civil War. The Union Intelligence Service was an intelligence organization created by Allan Pinkerton for the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. The service employed many spies and couriers, some of whom were women or African Americans who could blend in with the local population. The service also intercepted and decoded Confederate messages and used balloons and signal flags to gather and transmit information.

Pinkerton provided military intelligence to General George B. McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac. The Army of the Potomac was the main Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was formed in July 1861 after the First Battle of Bull Run and fought in many battles, such as Antietam, Gettysburg, and the Overland Campaign. It was led by several generals, including George B. McClellan, Joseph Hooker, and George G. Meade. It was disbanded in June 1865 after the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia surrendered.

Pinkerton’s network of undercover agents infiltrated the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, and other Southern territories, collecting information on Confederate troop numbers, movements, and morale. However, Pinkerton’s estimates of enemy strength were often inaccurate and inflated, leading to McClellan’s over cautiousness and missed opportunities.

In 1863, after Pinkerton resigned from his position, Major General Joseph Hooker established a new intelligence organization for the Army of the Potomac, called the Bureau of Military Information (BMI). The BMI was the first formal and organized American intelligence agency, active during the American Civil War. It was established in 1863 by Major General Joseph Hooker, who appointed Colonel George H. Sharpe as the head of the bureau. The BMI improved the methods and accuracy of intelligence gathering and analysis, using scouts, spies, prisoners of war, newspapers, maps, and aerial reconnaissance. The BMI also cooperated with other intelligence agencies in the Union army and navy, creating a more centralized and effective system of intelligence.

The BMI employed about 70 field agents and scouts, some of whom worked behind enemy lines in disguise. The BMI played a crucial role in several battles, such as Gettysburg, where it provided accurate intelligence on the Confederate army’s movements and strength. The BMI also assisted General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox and helped parole General Robert E. Lee. The BMI was dissolved in 1865 after the war ended.

Post Civil War

The work of Allan Pinkerton after the Civil War was mainly focused on expanding his detective agency and providing security services to businesses. He opened new offices in New York and Philadelphia, and hired more agents to meet the growing demand for his services.

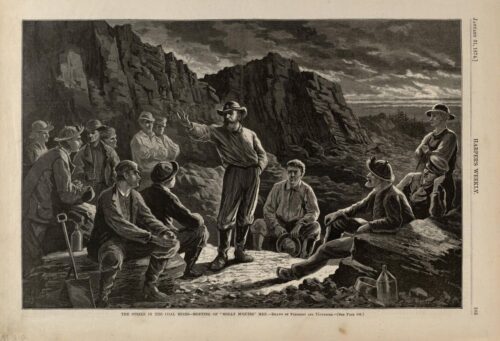

He specialized in railway theft cases, protecting trains and apprehending train robbers. He solved the $700,000 Adams Express Co. theft in 1866, which involved recovering stolen bonds and arresting several suspects. He also became involved in several high-profile cases, such as tracking down the James-Younger Gang, the Reno Gang, and the Molly Maguires.

Strikebreaker

However, his agency also gained a reputation for being anti-labor, as he often sided with employers against striking workers. The Pinkertons were hired by businesses to infiltrate unions, supply guards, keep strikers and suspected unionists out of factories, and recruit goon squads to intimidate workers. His agency was involved in some of the most violent labor conflicts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the Homestead Strike, the Pullman Strike, and the Ludlow Massacre. The Pinkertons were seen as enemies of the working class and a threat to democracy by many labor activists and reformers.

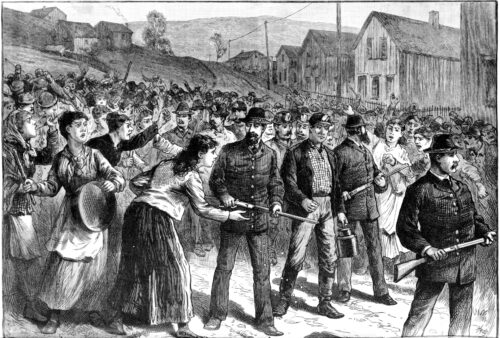

The Homestead Strike was a violent conflict between Carnegie Steel Company and the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, one of the largest unions in the country. The strike began on July 1, 1892, when Henry Clay Frick, the chairman of Carnegie Steel, announced pay cuts and locked out 3,800 workers from the Homestead plant near Pittsburgh. The workers voted to strike and surrounded the plant, preventing any strikebreakers from entering. Frick hired 300 Pinkerton agents to break through the workers’ blockade and secure the plant. On July 6, a bloody battle erupted when the Pinkertons arrived on barges along the Monongahela River. The workers fired at the barges and set them on fire, while the Pinkertons returned fire with rifles and revolvers. After a 14-hour standoff, the Pinkertons surrendered and were beaten by the angry mob of workers and townspeople. The battle left seven workers and three Pinkertons dead, and many more wounded.

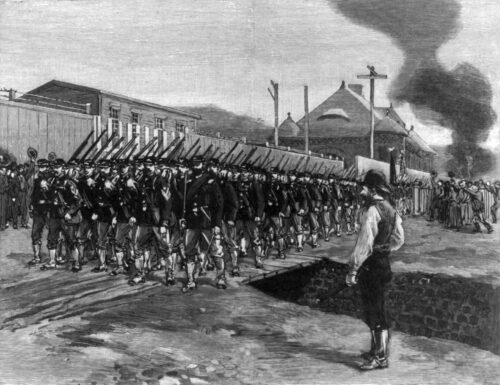

The governor of Pennsylvania sent in 8,000 National Guard troops to restore order and protect the strikebreakers who resumed work at the plant. The strike continued until November, but it gradually lost support and momentum as many workers left Homestead or accepted lower wages. The union was effectively crushed, and Carnegie Steel remained non-unionized until the 1930s.

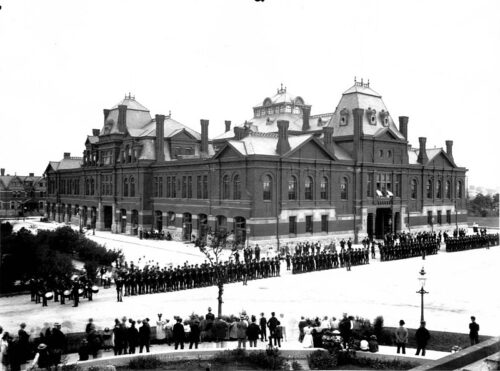

The Pullman Strike was a nationwide railroad strike in 1894 that pitted the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman Company, the main railroads, and the federal government. The strike began when Pullman workers protested wage cuts and poor living conditions in the company town of Pullman, Illinois. The ARU, led by Eugene V. Debs, supported the strike by refusing to handle Pullman cars. The railroads hired Pinkerton agents and other strikebreakers to confront the strikers, leading to violent clashes and deaths. The federal government intervened by sending troops to break the strike, claiming it was disrupting mail delivery and interstate commerce. The strike ended with a crushing defeat for the ARU and the imprisonment of Debs.

The Ludlow Massacre was a brutal suppression of a strike by coal miners in Colorado in 1914. The miners, who worked for the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I), owned by John D. Rockefeller Jr., went on strike to demand better pay, working conditions, and union recognition. They were evicted from their company-owned houses and set up tent colonies outside the mines. The CF&I hired Pinkerton agents and other gunmen to harass and attack the strikers, while the Colorado National Guard sided with the company. On April 20, 1914, the Guard and the gunmen assaulted the largest tent colony in Ludlow, killing dozens of people, including women and children who suffocated in a fire that destroyed the tents. The massacre sparked a ten-day war between the miners and the militia, which ended with federal intervention and a truce. The strike lasted until December 1914, but failed to achieve any of the miners’ demands.

Death and Legacy.

Pinkerton died on July 1, 1884, in Chicago, Illinois, from complications of a stroke. He was buried in Graceland Cemetery. His agency survived him and became one of the largest and most influential private security firms in the world. Today, the Pinkerton agency is a division of Securitas AB, a Swedish security company, and operates as Pinkerton Consulting & Investigations, Inc. doing business as Pinkerton Corporate Risk Management.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.