During the Cold War, satellites became silent sentinels orbiting high above Earth, tasked with watching adversaries from the heavens. Long before digital imaging and instant data transmission, reconnaissance relied on physical film, fragile strips of celluloid that had to survive the harsh environment of space and then return safely to Earth. The race to master this technology was as critical as the race to the Moon, for the intelligence gathered could tip the balance of global power.

Precursors to the KH‑9 Program

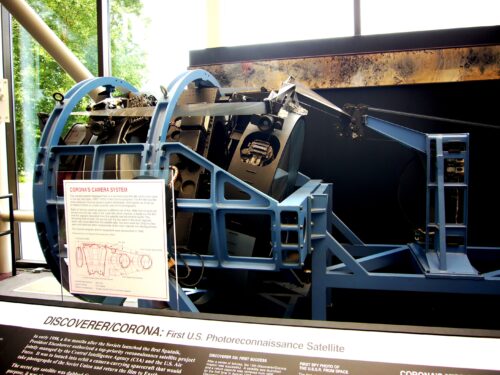

The KH‑9 HEXAGON did not emerge in isolation. It was the culmination of years of experimentation with earlier reconnaissance satellites under the CORONA program, which began in the late 1950s. Corona was the first successful U.S. effort to photograph Soviet territory from orbit, producing thousands of images that revealed missile sites, airfields, and industrial complexes. These satellites also relied on film-return capsules, which parachuted back to Earth for mid-air recovery.

While revolutionary, CORONA had limitations. Its cameras offered narrower fields of view, and the resolution was not always sufficient to identify smaller or camouflaged targets. By the late 1960s, as the Soviet Union expanded its nuclear arsenal and China emerged as another strategic concern, the United States needed a more powerful system. The answer was the KH‑9 HEXAGON, larger, more sophisticated, and capable of sweeping panoramic coverage that dwarfed its predecessors.

From CORONA to HEXAGON

The CORONA program, which ran from 1959 to 1972, was the United States’ first successful series of reconnaissance satellites. It revolutionized intelligence gathering by providing thousands of images of Soviet and Chinese military sites, but its technology was limited. CORONA’s cameras produced narrower coverage and lower resolution compared to what was needed by the early 1970s, when adversaries were rapidly expanding and concealing their nuclear forces.

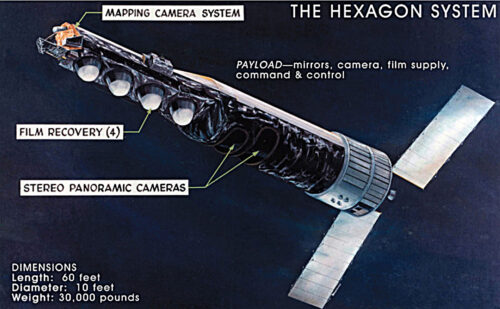

To overcome these shortcomings, the National Reconnaissance Office developed the KH‑9 HEXAGON, a far larger and more sophisticated successor. With panoramic cameras, multiple film-return capsules, and improved resolution, Hexagon offered sweeping views of entire regions, capabilities that made it the backbone of U.S. satellite reconnaissance for the next decade and a half.

The KH‑9 HEXAGON

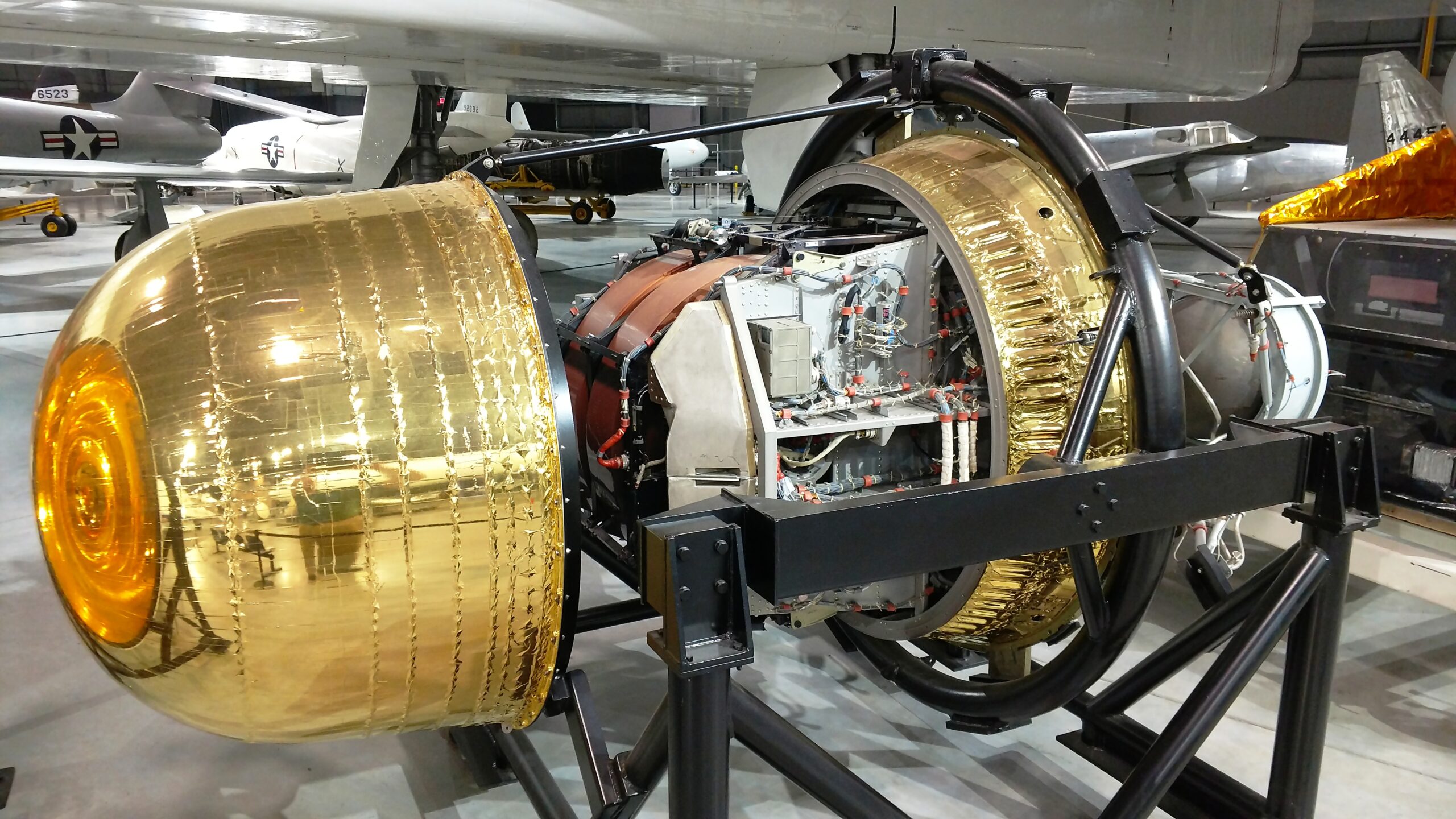

The KH‑9 HEXAGON, nicknamed Big Bird, was the United States’ most advanced photographic reconnaissance satellite of its time. Launched between 1971 and 1986, the KH-9 carried panoramic cameras capable of imaging vast swaths of Soviet and Chinese territory with resolutions sharp enough to identify missile silos, aircraft, and naval assets. Unlike modern digital satellites, the KH‑9 relied on physical film. Once exposed, the film was packed into reentry capsules nicknamed “buckets” that parachuted back to Earth. Ideally, U.S. Air Force C‑130 aircraft would snatch them mid-air, but if missed, the capsules could be recovered from the ocean.

A Capsule Lost at Sea

On the very first KH-9 mission in 1971, disaster struck. One of the film-return capsules splashed down in the Pacific but sank to an astonishing depth of 16,400 feet (5,000 meters). Inside was highly classified imagery of Soviet military installations, material too sensitive to abandon. Losing it risked not only intelligence gaps but also the possibility of foreign powers discovering the capsule.

The Secret Recovery Operation

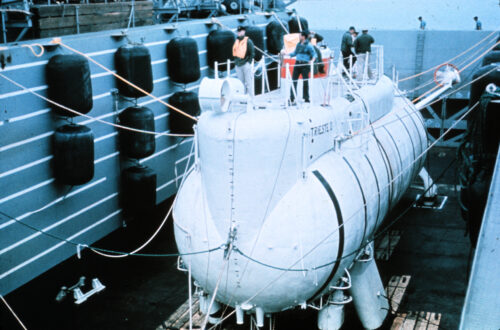

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and CIA quickly mobilized the U.S. Navy for a covert retrieval mission. The task fell to the Trieste II (DSV-1), a deep-submergence vessel originally designed for extreme depths. In April 1972, Trieste II descended into the abyss, equipped with a claw-like recovery device. Working in near-total darkness and crushing pressure, the crew managed to locate and retrieve the capsule from the ocean floor.

This operation was unprecedented. At the time, no one had attempted to recover such a small object from such depth. The mission tested the limits of deep-sea engineering and showcased America’s ability to protect its secrets even in the most hostile environments.

The recovery of the KH-9 capsule was a geopolitical necessity. The Cold War was defined by surveillance and secrecy, and the intelligence contained in those film reels was vital for monitoring Soviet missile deployments and verifying arms control agreements. Successfully retrieving the capsule demonstrated U.S. resolve and technological superiority in both space and undersea domains.

Legacy of the Mission

The KH-9 Hexagon program continued until 1986, with 20 satellites launched in total. Each carried multiple film-return capsules, and most were successfully recovered. The lost-and-found capsule of 1971 remains legendary, symbolizing the intersection of space exploration, espionage, and deep-sea adventure. Today, declassified accounts of the mission reveal just how far the U.S. was willing to go to safeguard its intelligence assets.

The KH-9 capsule recovery was a hidden Cold War drama, an underwater “space race” that proved America’s ability to reach not only the stars but also the deepest parts of the ocean to protect its secrets.