The double tap, hammer and aimed pairs, are all two quick sequential shots. They are an integral component to many drills. Often shooters have no idea why they are firing “two” shots or what the impact may be on their response in a deadly force situation. While it may be obvious to some there are some nuances and level of understanding that may help everyone if for no other reason a quick refresher.

The other day my wife’s uncle asked why I had her doing drills with three rounds to center of mass (COM) and one to the head as the traditional failure drill (Mozambique drill) consists of two rounds COM and one to the head. The answer touched on several issues that I thought would be an interesting subject for some. Now before I delve into the subject further, I’m not saying never shoot two shot strings. My message is, know what you are trying to achieve with your practice session. Let’s discuss that.

Yes, traditionally the Mozambique (also called Failure) Drill consists of two shots to COM and one to the head. It comes from a discussion LTC Jeff Cooper (patron saint of defensive shooting) had with a former student and acquaintance Mike Rousseau in the 70’s working as a mercenary in Africa. Rousseau engaged an AK47 armed rebel in a hallway with two shots COM which did not elicit the desired response. Rousseau raised his point of aim dropping the rebel with a shot to the neck severing the spinal column. Cooper created a drill based on the incident calling it the Mozambique Drill. (The incident allegedly occurred in the city of Maputo Mozambique.) Larry Mudgett and John Helms from LAPD’s SWAT unit attend training at Cooper’s Gunsite and took the drill back to their department renaming it with Cooper’s permission the more politically correct, Failure Drill.

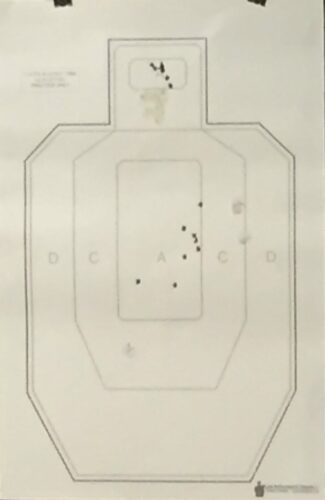

The point of the drill though is not to shoot a threat twice and elevate to the head. The point of the drill is for a shooter to realize COM impacting shots aren’t stopping the threat and the shooter needs to try something else. Constantly training 2 & 1 may contribute to doing just that in a real situation. It’ll work if that last shot hits the “T-box” but hitting the head under stress is much more difficult than hitting center mass and may even be beyond a shooter’s skill at that moment while 3, 4 or 5 shots to COM may stop the threat. Also practicing by rote “2 to the chest, 1 to the head” misses the point that the shooter needs to be assessing for target effects.

Always shooting two rounds can solidify a habit or training scar of firing two rounds that may carry over into a self-defense situation where three, four or five rounds might be necessary. How many times has one gone to the range and one hears a fellow shooter in the next booth going through magazine after magazine of ammo firing two shots? Do they do that every time they visit the range? Most of the time?

When one shoots, mix up the number of shots in a given drill. Of course, this doesn’t apply to a timed drill that has a two-shot string as the value is lost if the goal is to compare one’s performance across a group or stated standard. Multiple shot strings also provide the added benefit of reinforcing recoil management as well as developing the habit of a follow-on sight picture helping one’s follow-through. Most importantly though, the primary reason is to communicate to oneself more than two shots may be necessary to stop a threat.

Another issue with two shot strings is many shooters practice the “double tap” (also called hammer pairs). This is an older technique to defensive shooting (derived from the Mozambique Drill) that has its place when properly employed. The double tap is two shots fired in quick succession without aiming the second shot. This is fine at extremely close ranges or with especially adept shooters especially when there is more than one assailant requiring a transition to a second target.

A more current approach is the “aimed pairs” technique. Aimed pairs require each shot to be aimed. One is still shooting fast, but each shot must hit its target. This reinforces the principle of “getting one’s hits” vs. making noise and going fast. When I train clients, I’m a huge proponent of getting hits over speed (of course not exclusive of speed). Putting hits on target is an integral component of the shot placement vs. caliber debate and I am a disciple of the “shot placement is king” perspective.

A .22 in the eye will stop Goliath. Now I’m not promoting the .22 as a self-defense round (9mm as the minimum please). Too many try to use quantity or caliber to solve the bad guy equation above placement. I’m a proponent for rigorously training oneself to aim to increase the chance one will do that in a gunfight.

It’s commonly taught one isn’t going to aim in a gunfight, just point shoot. That’s not an inaccurate observation for many gunfights, it’s also a lazy man’s approach and creates a level of legal jeopardy by minimizing the importance of aimed shots. There’s a lot of value to point shooting but too many rely on that alone to save their lives and while it may, luck isn’t a method. It’s also a great way to shoot a bystander.

Another derogatory impact of always shooting two round strings is one may get a false perception on the adequacy of a firearm for self-defense. E.G. one may be able to get three two-shot engagements from a six-shot revolver or semi-auto pistol. That does not necessarily equate to being able to stop three assailants in the real world. It also isn’t indicative of how quickly six shots may be expended in a gunfight. Together, that may give one a false sense of security reference the capability of one’s firearm.

My final issue with always or heavily relying on two shot drills is the impact on one’s reloading skills. It’s intuitively obvious one will be able to do a lot of two shot strings with a large capacity pistol. While we may debate the efficacy of being able to reload (some believe they won’t have to reload and/or don’t carry a spare magazine), the benefit to reloading is not just getting more bang in the gun. It’s also forcing oneself to reacquire one’s grip and aim, often in the middle of an exercise. This is a pretty important defensive skill and has a lot of real-world application. Imagine defending oneself and being knocked to the ground or having to push a loved one out of the way and continue the fight.

I’ve used a lot of hedging language and I’ve done that in recognition that a lot of readers here are advanced shooters. I also don’t want the reader to miss my key point which isn’t “two-shot strings are bad”. What I’m trying to say is don’t do them all or even most of the time. Have a goal for your shooting session. Mix up your defensive shooting drills with different continuous strings of fire. Try three, four and five shot strings in your range visits. I’m not the only one that believes this as this fundamental point has been emphasized in classes I’ve taken by Tom Givens, Aaron Cowan and my friend and fellow contributor Jon Dufresne.

Whatever you do. Have a plan on what you want to train for during a range session. Understand the goals of a specific drill you may choose and train to the goal not the drill. Be safe, have fun and think about what you are trying to achieve.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.