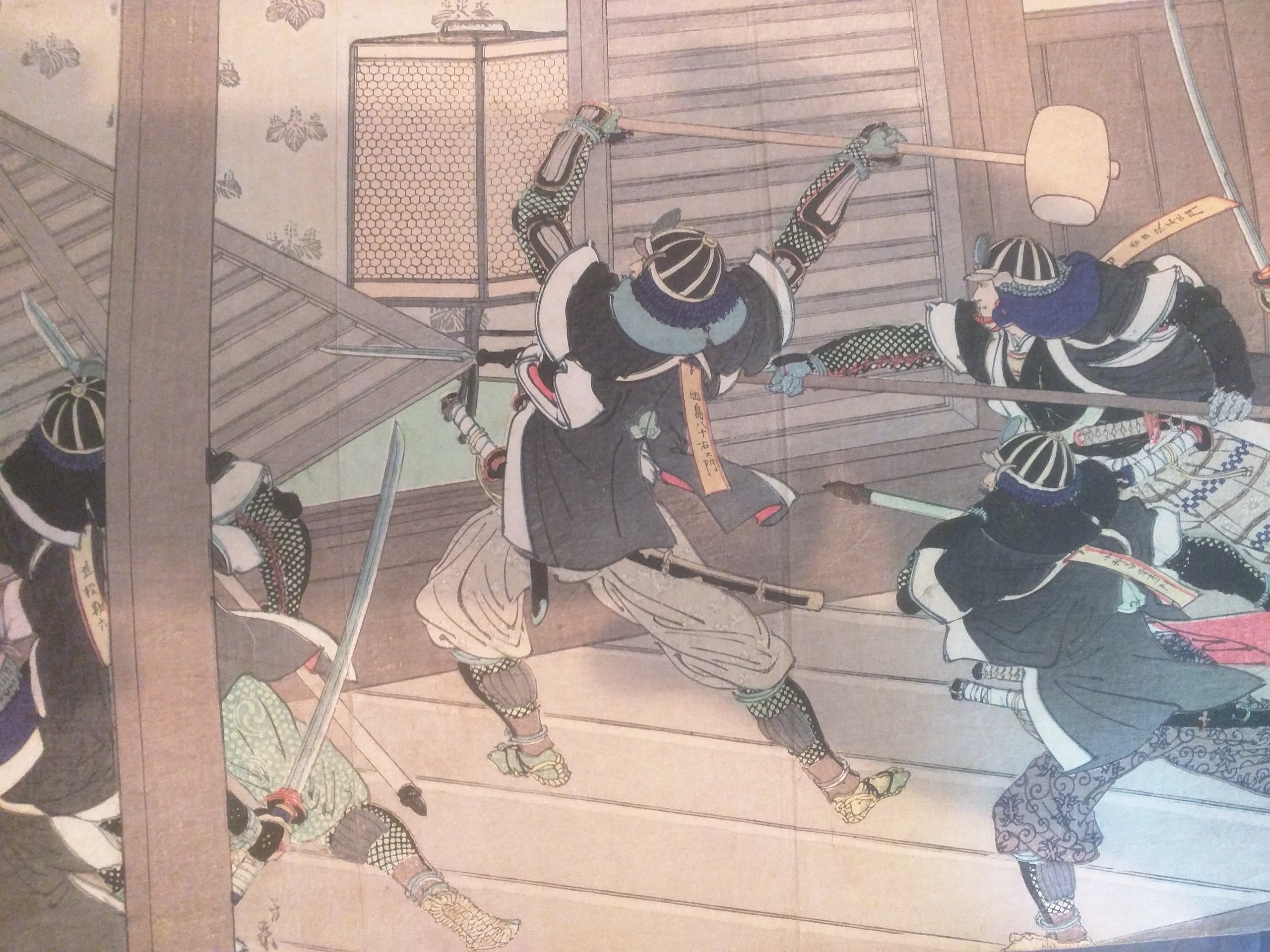

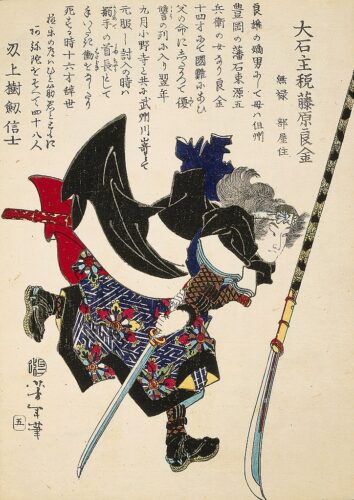

Scan from an original woodblock print by Shikazaki Ryuu circa 1890. Depicts the true tale of the revenge of the 47 Rōnin.

During the feudal era of Japan (1185–1868 AD), the term ‘rōnin’ was used to describe a particular class of samurai who were not in service to a lord or master. In some instances, these individuals had also cut ties with their family or clan. The word ‘rōnin’ is often translated as ‘drifter’ or ‘wanderer’. However, in the kanji script, ‘rō’ (浪) signifies a ‘wave’ or something ‘unrestrained’, and ‘nin’ (人) denotes a ‘man’ or ‘person’.

The term ‘rōnin’ first appeared during the Nara and Heian periods, where it was used to label a serf who had abandoned or escaped from his master’s land. As time progressed into the medieval era, rōnin came to be seen as the outcasts of the samurai class, lacking a master and thus, honor. The term ‘wave man’ was then adopted to depict a samurai without a master, symbolizing a person adrift in society.

Warrior Code and Status

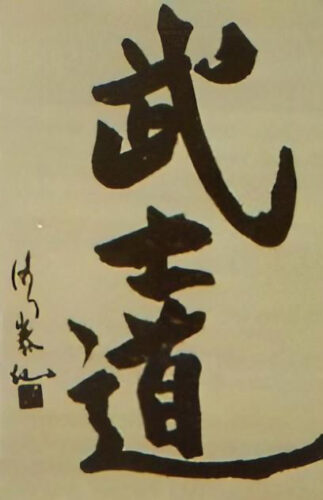

According to the Bushido Shoshinshu, or the ‘Warrior’s Code’, a samurai was expected to perform seppuku (also known as harakiri, a ritual suicide involving disembowelment) if they lost their master. Those who chose not to follow this code were left to their own devices, often facing severe shame. The stigma associated with the status of a rōnin was primarily enforced by other samurai and daimyō, the feudal lords.

The Bushido Shoshinshu, often referred to as the “Beginner’s Guide to Bushido”, is indeed a significant text for understanding Bushido, the samurai code. Authored by Taira Shigesuke around 1700 AD, this guide was intended to educate young samurais of the peaceful Edo Period (also known as the Tokugawa Period) who had not experienced the hardships of battle, providing them with practical philosophies from previous eras.

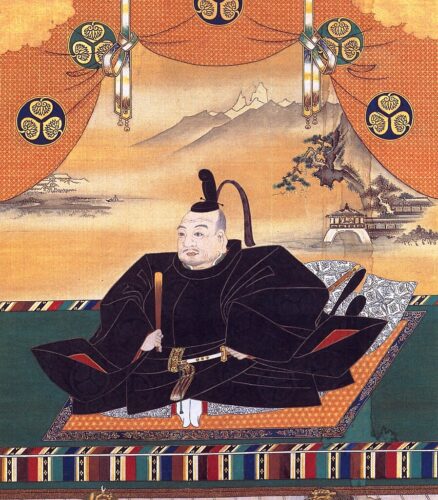

The Edo Period (1603 to 1868) marks the governance of the Edo or Tokugawa shogunate, which was officially established in 1603 by the first Edo shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu. The period derives its name from the city of Edo, known today as Tokyo.

This text continues to be a valuable resource for those studying samurai culture and the principles of Bushido. Bushido, which translates to “the path of the warrior”, is a code of ethics that shapes the attitudes, behaviors, and way of life of a samurai. This code was formalized during the Edo Period and has undergone significant evolution throughout history. The code underscores a blend of sincerity, frugality, loyalty, mastery of martial arts, honor unto death, courage, and allegiance to the samurai’s lord.

The Bushido Shoshinshu offers both practical and moral guidance for warriors, rectifying errant tendencies and defining the personal, social, and professional conduct standards characteristic of Bushido, the chivalric tradition of Japan. It continues to shape modern Japanese martial arts and the socio-economic structure of Japan.

Weapons and Armor

Rōnin, like their samurai counterparts, were known to carry two swords, known collectively as “daisho”. The katana, the primary weapon for combat, was complemented by the wakizashi, which was often utilized in close quarters combat or served as a secondary weapon. This was a symbol of their status and was a common practice among the warrior class in feudal Japan. However, their weaponry was not confined to these two blades.

In addition to their swords, rōnin often carried other weapons, expanding their arsenal based on their needs and circumstances. Those who were economically disadvantaged often carried a bō, a staff approximately 1.5 to 1.8 meters (5 to 6 feet) in length. This weapon was versatile and could be used both for offense and defense.

Another weapon commonly used by rōnin was the jō, a smaller staff or walking stick measuring around 0.9 to 1.5 meters (3 to 5 feet). This weapon was easier to carry and could be used in more confined spaces, making it a practical choice for many rōnin.

Some rōnin also carried a yumi, a type of bow. This allowed them to engage enemies from a distance, adding a level of versatility to their combat capabilities.

Much like their samurai counterparts, a rōnin typically donned traditional Japanese armor, referred to as “yoroi” or “tosei-gusoku”. This armor was engineered to offer protection to the wearer while ensuring they retained mobility. It was constructed from a blend of metal and leather plates, which were interconnected with vibrant cords.

Not all rōnin had the financial means to afford a complete set of armor or high-quality swords. Those who faced financial limitations often resorted to using whatever gear they could afford or obtain.

Rise of the Rōnin

During the Edo Period, the number of rōnin, or masterless samurai, saw a substantial rise. This increase was largely due to the stringent class system and laws enforced by the shogunate. The societal structure during this time was rigid, and the laws often led to samurai losing their status and becoming rōnin.

One significant event that contributed to the surge in the rōnin population was the confiscation of fiefs under the rule of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shōgun of the Tokugawa dynasty. Iemitsu’s policies and actions resulted in many samurai losing their lands and, consequently, their status. This led to a marked increase in the number of rōnin during his rule. The rise in the number of rōnin had significant social and cultural implications. It led to an increase in social unrest and contributed to the eventual end of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Notable Rōnin

Several rōnin have left indelible marks on Japanese history and culture, their stories serving as reminders of a turbulent and transformative era in Japan’s history. Among the most notable are the Forty-seven Rōnin, a group renowned for their loyalty and revenge following their master’s death, a tale that has become one of Japan’s most famous stories. Another significant figure is Kyokutei Bakin, a celebrated novelist of the late Edo period known for works such as Nansō Satomi Hakkenden and Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki. Miyamoto Musashi, hailed as Japan’s greatest swordsman, was not only a rōnin but also a philosopher, writer, and artist. Musashi authored the This seminal text on kenjutsu and martial arts The Book of Five Rings around 1645, which offers deep understanding into strategic thinking and the artistry of swordsmanship. Sakamoto Ryōma played a pivotal role in the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate during the Bakumatsu period. Yamada Nagamasa, a rōnin who ascended to the position of a high-ranking advisor to the king of Ayutthaya in the early 17th century, is also worth mentioning.

Final Thoughts

The rōnin, with their distinctive status and history, have left an indelible imprint on Japanese culture and society. Their narratives continue to fascinate audiences, serving as a poignant reminder of a tumultuous and transformative period in Japan’s history.

The concept of the rōnin has also been adopted and adapted in various forms of media and entertainment around the world. The image of the wandering, masterless samurai has been romanticized and popularized in films, literature, and even video games. These portrayals often emphasize the rōnin’s independence, resilience, and martial prowess, and they sometimes explore the challenges and hardships they faced.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.