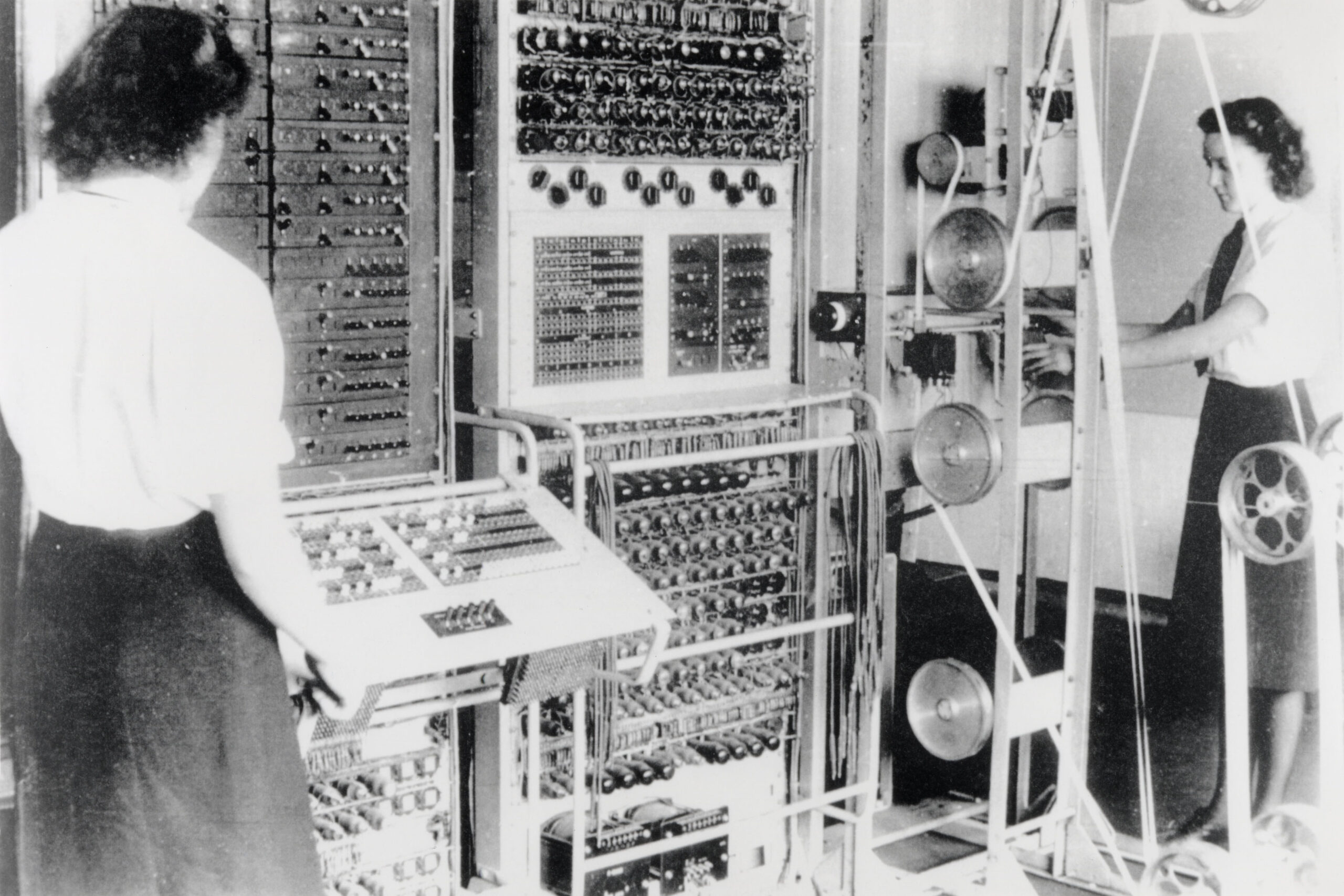

A Colossus Mark 2 codebreaking computer being operated by Wrens (Women’s Royal Naval Service) in 1943.

January 18, 2024, marks the 80th anniversary of Colossus, the world’s first digital computer, which played a pivotal role in the Allied victory during World War II.

The Genesis of Colossus

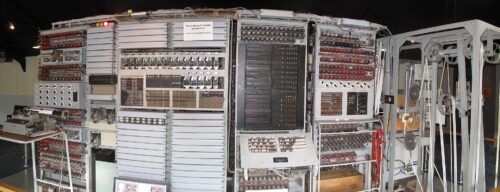

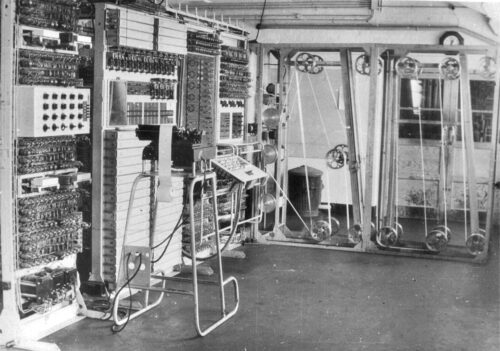

Colossus was born out of the necessity to decode encrypted German communications rapidly. Operational from early 1944 at Bletchley Park, the heart of the UK’s wartime code-breaking efforts, Colossus was shrouded in secrecy until the early 2000s. Engineered by Thomas Harold “Tommy” Flowers, Colossus was a two-meter-tall frame of switches and plugs draped in wires. It used 2,500 thermionic valves (vacuum tubes) to process information faster than ever before, cutting the time it took to decode messages to hours from weeks.

Flowers was an English engineer with the British General Post Office. Flowers was born in Poplar, London’s East End in 1905. While undertaking an apprenticeship in mechanical engineering at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, he took evening classes at the University of London to earn a degree in electrical engineering. In 1926, he joined the telecommunications branch of the General Post Office (GPO), moving to the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in northwest London in 1930.

Flowers’ first contact with wartime codebreaking came in February 1941 when Alan Turing, who was working at Bletchley Park, asked for his help. Turing wanted Flowers to build a counter for the relay-based Bombe machine, which Turing had developed to help decrypt German Enigma codes. Although the “Counter” project was abandoned, Turing was impressed with Flowers’s work, and in February 1943 introduced him to Max Newman who was leading the effort to automate part of the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher. Flowers worked with Turing on the Enigma project and was later put in charge of the team that built Colossus. The first Colossus was delivered to Bletchley Park, which was the secret base of the Government Code and Cypher Schoo (GC&CS). on January 18, 1944.

The Impact & Legacy of Colossus

By the end of the war, ten such computers were actively decrypting a staggering 63 million characters of high-grade German communications. One of its notable successes was helping the Allies know that Hitler had swallowed the bait that the D-Day landings in June 1944 would be at Calais rather than Normandy. Historians believe that the computers shortened the war and saved many lives.

Despite its significant impact, the existence of Colossus was kept from the history books for almost six decades. After the war, eight of the ten computers were destroyed, and all documentation on the machinery was handed over to Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). The secrecy was s successful that even engineers who worked on Colossus in the 1960s had no idea about its wartime role. However, the legacy of Colossus lives on, and it is considered by many to be the first ever digital computer.

Government Communications Headquarters

Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) is an intelligence and security organization that provides signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the UK It is the British equivalent of the US National Security Agency (NSA).

GCHQ was originally established after the First World War as the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS). It is now primarily based at “The Doughnut” in the suburbs of Cheltenham, England. The organization is responsible for gathering information through the Composite Signals Organisation (CSO) and securing the UK’s own communications through the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). The Joint Technical Language Service (JTLS) is a small department and cross-government resource responsible for mainly technical language support and translation and interpreting services across government departments.

The 80th Anniversary Celebration

In celebration of the 80th anniversary of Colossus, GCHQ has unveiled a collection of previously unreleased images and sounds. These materials provide fresh insights into the origins and operations of Colossus, reminding us of the innovative spirit and creativity essential for our protection.

As we commemorate the 80th anniversary of Colossus, we honor the trailblazers of computing whose efforts played a crucial role in bringing World War II to a close. Their enduring legacy continues to fuel technological advancements and serves as a reminder of how technology has the power to transform our world.

Resources

Bletchley Park

BletchleyPark.org.uk

The National Museum of Computing

TNMOC.org

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.