WWI marked a pivotal moment in the 20th century, propelling cigarette usage to the forefront of tobacco consumption. This war introduced numerous modern military conventions, encompassing automatic weapons, mass casualties, total war with the deliberate targeting of civilian populations, advancements in air and submarine warfare, the use of chemical weapons, and various other innovations. Among these innovations, one stood out, impacting both soldiers and societies with enduring and potentially costly consequences well beyond the armistice: the cigarette.

In his work “Cigarette Pack Art” (1979: 24), Mullen traces the introduction of cigarettes in Britain back to the Great Exhibition of 1851. During this event, two tobacconists, Bacon’s (Cambridge) and Simmons (London), are documented as selling cigarettes rather than cigars. Following this, returning military personnel from the Crimean War played a significant role in popularizing cigarette smoking, a habit seemingly acquired from Turkish and Russian soldiers. Consequently, the inaugural cigarette manufactory in Britain was established by Robert Gloag in London in 1856.

Over the subsequent twenty-five years, cigarettes were crafted by hand, which maintained their elevated cost and placed them beyond the economic reach of working-class smokers. It’s worth noting that during this period, working-class smokers could obtain clay pipes for free in public houses. Despite their military associations, cigarettes still carried a perception of effeminacy and foreignness at that time (Hilton, op. cit.: 26-28). 1

Preceding the war, various anti-tobacco movements, championed by progressive religious organizations like the National Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), advocated for policies prohibiting tobacco sales. In fact, some states, including Indiana, Nebraska, and Idaho, had enacted laws banning cigarettes. However, the dynamics shifted with the onset of WWI.

Although cigarettes were not a novel invention during World War I, the conflict played a pivotal role in popularizing them, turning them into a ubiquitous element of 20th-century smoking culture. More user-friendly than pipe tobacco and more affordable than cigars, cigarettes found an ideal place in the trenches. They helped conceal the odors of death and decay, provided solace to anxious soldiers, and were routinely distributed to wounded and dying troops.

The warfare during WWI was characterized by static battles, where soldiers oscillated between prolonged waiting periods and engaging in day-long artillery barrages within trenches fraught with death and chaos. Smoking became a coping mechanism for soldiers dealing with both stress and boredom. Notably, leaders like General John Pershing deemed cigarettes crucial for troop morale, asserting their importance in wartime was on par with bullets.

General Pershing said “You ask me what we need to win this war. I answer tobacco as much as bullets. Tobacco is as indispensable as the daily ration; we must have thousands of tons without delay.”

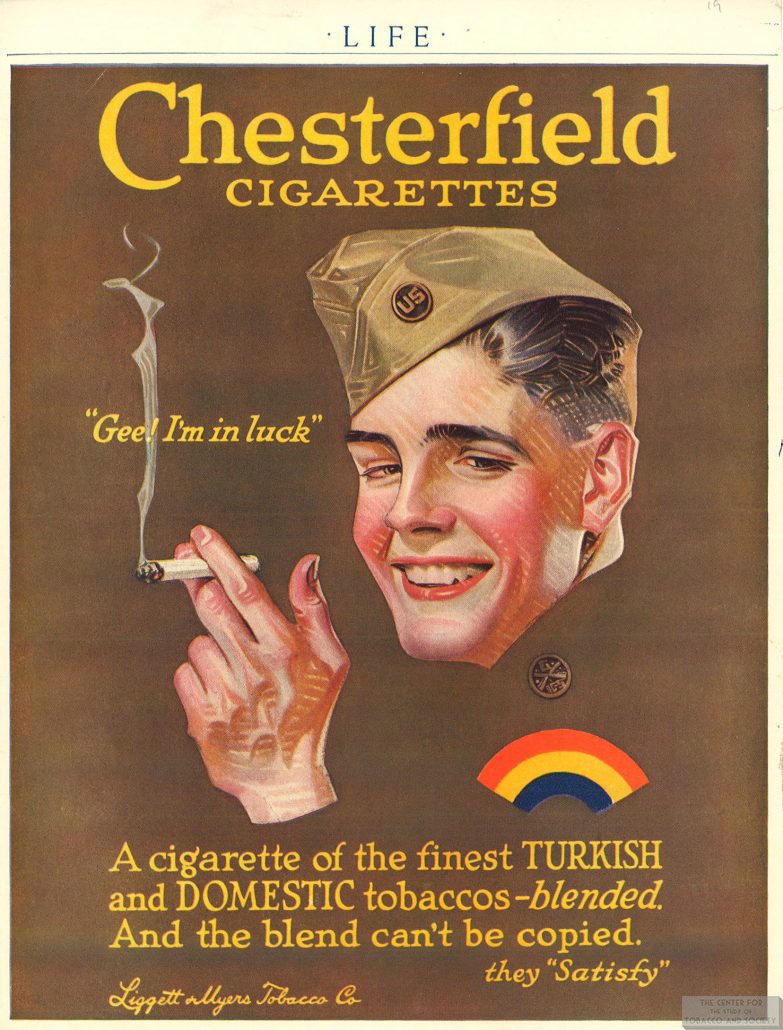

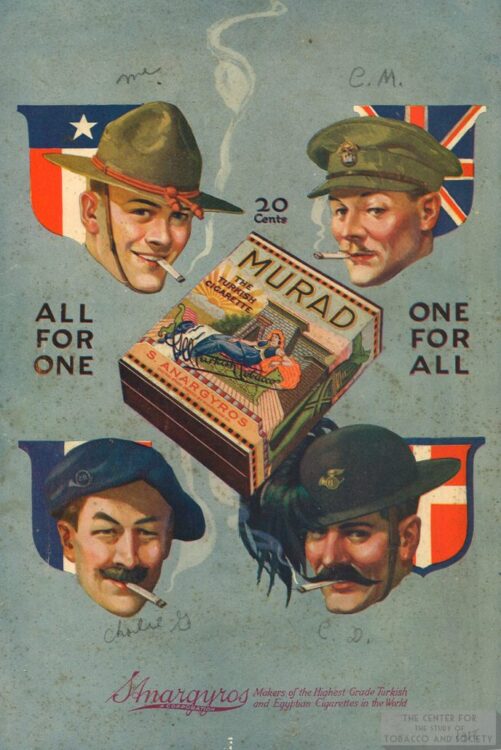

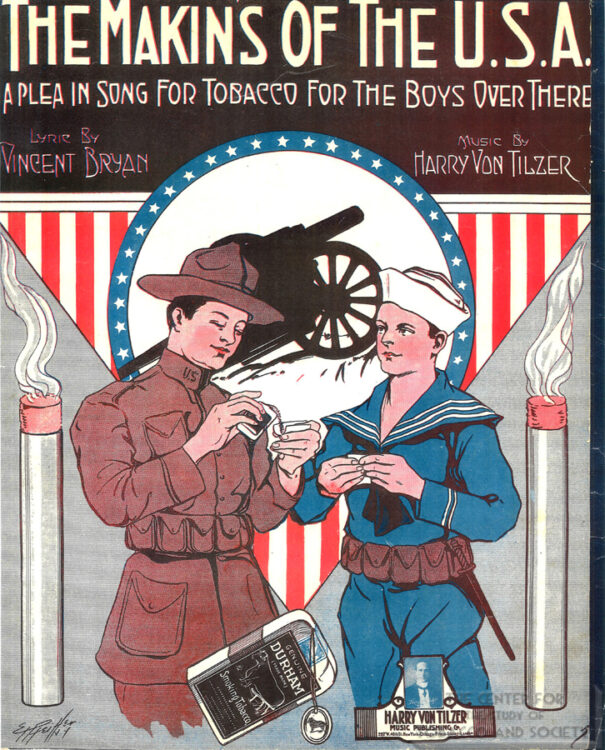

Tobacco became highly valued as a wartime necessity, a sentiment that the tobacco industry skillfully exploited in its advertising campaigns featuring soldiers, flags, and the symbols of a triumphant nation safeguarding democracy. Back home, tobacco funds were established to “send smokes to the boys,” ultimately dispatching a staggering 16 billion cigarettes as part of relief efforts by the war’s conclusion.

Initially, pipe smoking was more prevalent, seen as a masculine activity with armies even rationing loose-leaf pipe tobacco. However, the fragility of pipes in battle and the difficulty of keeping loose-leaf tobacco dry in the trenches led to the ascendancy of the pocket cigarette, designed for convenient transport, as the quintessential tobacco product for WWI soldiers.

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) initially received cigarettes through canteens—stations selling non-rationed goods operated by civilian organizations. Cigarette companies seized the opportunity, creating advertisements in newspapers and magazines with patriotic themes to persuade soldiers to buy their brands. These ads often portrayed cigarette brands as fostering bonds between Allied troops, individual soldiers, and their families.

General March later brought canteens under army control, instituting the official policy of rationing soldiers four ready-made cigarettes per day. This ration increased over time, reaching 12 to 28 army-provided cigarettes per day during the Second World War. As veterans returned post-WWI, they brought their smoking habits home, contributing to the decline of the anti-tobacco movement. Their argument, “If cigarettes were good enough for us while we were fighting in France, why aren’t they good enough for us in our own homes?”

The First World War not only shaped America but also solidified the cigarette as a driving force behind the tobacco industry. However, this newfound popularity came at a cost, as the cigarette became a lasting affliction for those who fought. Prior to the war, instances of lung cancer were rare and exceptional. In the decades following the war, the disease became more prevalent, disproportionately affecting veterans who had taken up smoking during the Great War. World War I propelled America onto the global stage, and among the essentials for its fighting forces, cigarettes played a crucial role. The slogan of Bull Durham Smoking Tobacco, “The Makin’s of a Nation,” accurately reflected the substantial contribution of tobacco to military morale. It would take nearly two decades for doctors to recognize the adverse health effects of cigarette smoking, over five decades for government health agencies to acknowledge the smoking-related disease pandemic, and nearly a century to address the problem comprehensively.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.

SOURCE

- https://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/218

- https://tobacco.stanford.edu/cigarettes/war-aviation/world-war-i/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smoking_in_the_United_States_military