Anger. Fear. Vulnerability. I could go on and on describing the feelings invoked on the human psyche after a school shooting is broadcast around the World. It may not even happen in your town and these events will still be shocking to your conscious. In our rage, we want answers, why did this happen? How could we have prevented this from happening? What is my kid’s school doing to protect them?

We will, in all likelihood, never know why these happen or how we could’ve prevented these events. In many cases, shooters have romanticized this event and have developed an exit strategy that does not include being taken into custody. The event lasts only minutes which means that they are typically over prior to law enforcement’s arrival. This leads us to our last question, “What is my kid’s school doing to protect them?”. For the answer to this, we turn to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Where it comes from

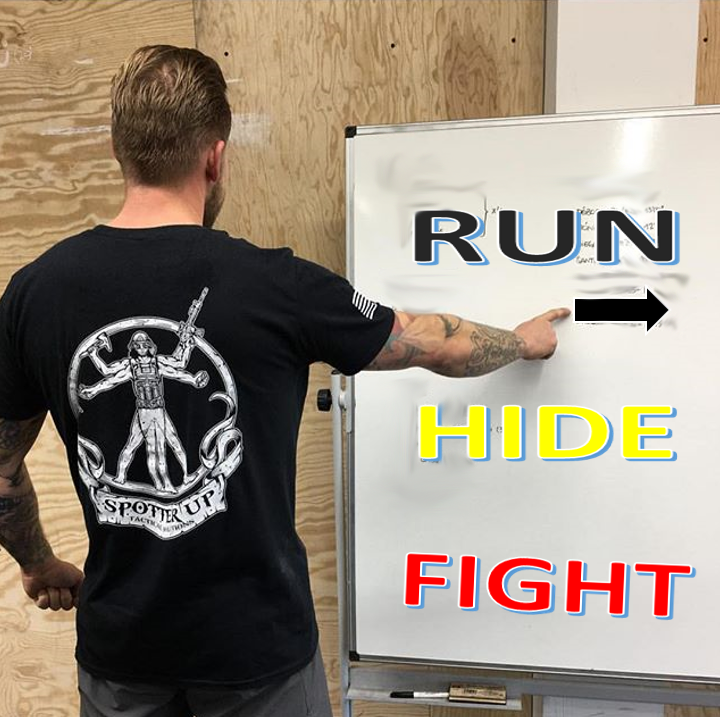

Post Sandy Hook, DHS developed the response strategy of “Run, hide, fight”. It has since been adapted and implemented around the country to a variety of audiences ranging from businesses to churches to schools. Every organization that teaches it to the public has subtle nuances to how they teach it, for the purposes of this article, I am sharing how I have taught it to school districts in Pima County, Arizona.

Think.

The first idea that we explain to our staff is that they need to think. Processing information is key to formulating our responses. We teach them about the What If? game and overcoming our sympathetic reflexes (fight, flight or freeze). We explain to them that these events are fluid and that our response to them has to be fluid as well. What this means is that not every situation is the same, nor will it remain as it was when it started. The idea is that, you may start the incident with running and be put in a situation where you have to find a place to hide or vise versa. After presenting these concepts, we move into the core of the “run, hide, fight” strategy.

Run

When we talk about “Run” it is critical that we are processing information. Running is an excellent idea when the shooter is not in your vicinity or there is a window for escape. To know whether the shooter is in your vicinity, there are a few variables. Did we know where the shooter was when the incident started? Are we hearing stimulus (screaming, gunshots) nearby or do they sound further out? Are you familiar enough with gunshots to make that determination? Running is meant to be taken literally; if a threat has presented itself in such a way that you have the ability to escape the place where the shooting is occurring, leave quickly. It is better to be lost in a nearby neighborhood and alive than located where the shooting happened and dead.

Hide

The concept of hide seems fairly self-explanatory on its surface, but diving into some of the strategies around it yield a complicated idea. When we teach schools to hide, it’s mated to the concept already in place, which is “lock down”. If you are unfamiliar with the term, lock down, it means that teachers lock their doors, shut off the lights and attempt to make their rooms appear unoccupied. An additional concept suggested to teachers in this training is that they barricade the door with anything to buy them time. We also suggest that they spread their students around the room.

This creates a “shooter’s dilemma” in that the shooter has to pick a person to target instead of an amassed group of people. This opens the window for another person, who is so inclined, to act against the shooter. The last point that we drive home here is that it is important that when we hide, we are not sitting in the dark waiting to die. I like to propose that instead, we are laying in wait, setting a trap and that anyone who enters our rooms to do bad things to our students is going to regret that they did so.

Fight

That brings us to fight. It is sometimes taught that fighting should be our last option. That is absolutely irresponsible and absurd. If a window is opened that the onset of an active shooter incident, for a person to intervene and use calculated and dynamic violence against a shooter, why would we want fight to be a last option in the back of their mind? If we choose to fight back against a shooter, we are forcing them to respond to our action, which takes time for them to react. In this window, there is opportunity for us to take control back from the shooter and end the incident. As a caveat, if we choose to respond to a shooter with violent action, we must be fully committed to this action. Anyone who has ever been in a physical confrontation before can attest that being half way committed to your personal protection will produce a yield that is equal to half of your capability.

My favorite example of someone who chose to fight back against an active shooter is Bill Badger. On January 8th, 2011, a gunman opened fire on a crowd at a political meet and greet. After the gunman opened fire, Bill Badger (whom had already been struck in the head by a bullet) jumped on him, subduing him. Several others jumped on the shooter at this point, with another person wrestling the gun away from him. In the subsequent hours, the face and head of the shooter began to swell up and become oblong. This is because in the pile of people who subdued him, he was punched repeatedly. None of those who chose to act against the shooter on that day look like they would be cast as Marvel’s next super hero. They were everyday people thrust into tragedy who had enough.

Bill Badger’s legacy is one of heroism.

Successful Implementation

We have other examples of how the Run, Hide, Fight response strategy has been implemented and effective against active shooter situations. In Mattoon, Illinois, when a student gunman opened fire in a cafeteria, a female teacher grabbed ahold of the gun and, with the assistance of others, was able to subdue that gunman. In Rancho Tehama, California, a gunman entered an elementary school after killing several people in a nearby neighborhood. The school went into lockdown with all of the staff and students going into hiding. The gunman shot into several classrooms before giving up on the school but no one in the school was killed.

The more that these types of response strategies are considered and taught to our school staff, the less tragedy we will see when they do happen. There will never be a perfect “if this, then that” prescribed response for an active shooter. I would encourage anyone who reads this to reach out to their kid’s, grandkid’s, nephew’s, nieces’ schools and push them to become familiar these types of response programs. Until we figure our how to stop active shooter incidents, training teachers on response to them is our best hope to protect our kids.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.

[…] Run, Hide, Fight. Active shooter response strategy for teachers. […]

[…] Run, Hide, Fight. Active shooter response strategy for teachers. […]

[…] Run, Hide, Fight. Active shooter response strategy for teachers. […]

Where does this plague of “lone gunman” come from? I know many will blame society’s decay, but two books come to mind that offer more answers. One is “Programed to Kill” by Dave McGowan and the other is “The Copycat Effect” by Loren Coleman. Worth you time.