My father spent 10 years in Vietnam, and told me about the story of the Khaki Mafia. He stated that if I wanted to speak with his good friend Bob Everett (Uncle Bob), that Bob would have some insight to share. Bob was the ship steward for William John Crum for many years. William John Crum (24 June 1918 – 5 February 1977) was an American businessman who was involved in black market operations in South Korea and South Vietnam and became known as the “money king of Vietnam.” I declined because I thought that the story had already been told, and I didn’t think there would be much interest. What could I add 40 years after a story had already been told?

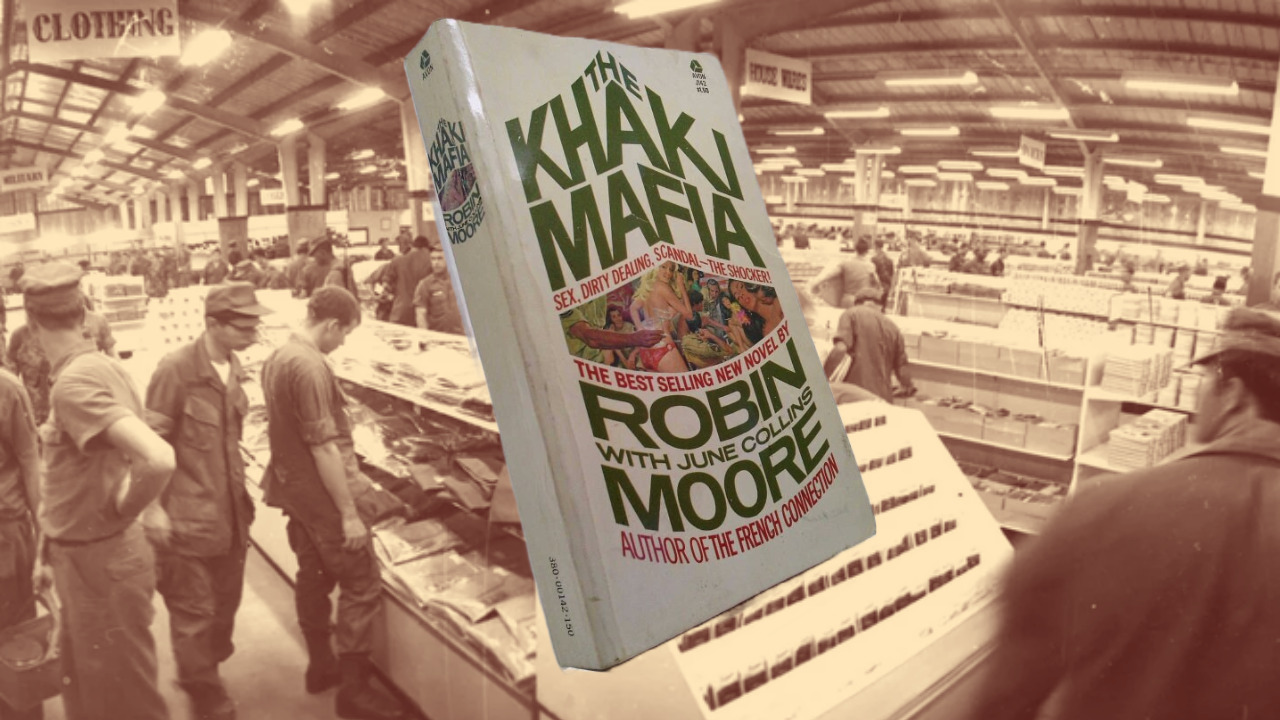

Robin Moore uncovered the existence of the Khaki Mafia during his time in Vietnam. He as the author wrote the book, “The Green Berets,”. His book provided a gripping and often controversial exploration of the war and the power structures that operated behind the scenes. Moore’s work brought forth a once hidden world to its readers. The Khaki Mafia—was a term Moore used to describe the network of influential officers and non-commissioned personnel within the military hierarchy.

He wrote that this group, often operating in the logistical and administrative spheres, held significant power and influence over critical aspects of military operations. This once clandestine group controlled vital resources, including supplies, transportation, and intelligence. Because they could manipulate the resources. they were able to exert influence over the war effort. There machinations impacted strategic decisions and shaped outcomes on the ground. In fact, The Senate investigation concluded that Crum’s Vietnam business was worth in excess of $40 million. By comparison, a study released in November 1966 found that up to 40% or US$1 billion of U.S. aid to South Vietnam had been lost due to corruption.

Their connections enabled them to navigate complex networks of influence, capitalizing on economic and political opportunities that emerged during the war. Moore’s accounts revealed their connections to local Vietnamese power brokers, government officials, and even international actors. Moore did not portray that all who were engaged used their power for personal gain or profit. He believed that some put genuine effort into support the war effort in order to ensure the welfare of frontline soldiers.

Some hailed Moore’s work for unmasking the hidden power structures within the Vietnam War, while others criticized his portrayals as overly sensationalized or questioned the accuracy of his claims. Regardless of the debates surrounding Moore’s work, it is undeniable that he played a significant role. He brought the concept of the Khaki Mafia to public attention. His writing initiated discussions and prompted further examination of the power structure and influence. The novel, the Khaki Mafia, had a fictional character in a criminal cartel based on Command Sergeant Major of MACV, Wooldridge. It was written by June Collins and Robin Moore. If you get a moment, give the book a read.

Command Sergeant Major of MACV, Wooldridge together with American businessman William J. Crum arranged to have Sergeant William Higdon appointed as custodian of the NCO club system at Long Binh Post in November 1967. Testimony was given that between then and July 1968 Crum paid a total of approximately US$60,000 of kickbacks from the slot machine operations. Wooldridge also brokered a deal between Crum and Maredem Inc. (a company owned by Wooldridge, Higdon and Sergeant Hatcher, the custodian of the 1st Infantry Division NCO clubs) in August of 1968 under which Maredem would have the monopoly on snack items in the NCO clubs while Crum would have the monopoly on slot machines. In 1973 the Department of Justice and Wooldridge reached an agreement whereby Wooldridge pleaded guilty to accepting stock equity from Maredem. Wooldridge had been awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal earlier, but it was revoked following this episode.

William John Crum was a key figure in the United States Senate investigation in 1971 into fraud and corruption in the management of military club systems known as the PX Scandal. After working odd jobs, Crum joined the Merchant Marine and returned to the Orient. In 1946 he was a freight solicitor for American President Lines in Shanghai, but was reportedly fired for dealing in U.S. currency in the black market. He later operated a radio station, XMHA in Shanghai and was married to his second wife, Russian Tantina Antonia Andrews.[1]: 874 In 1950 Crum moved to Japan and then South Korea where he sold liquor and other supplies to the United States Army open mess systems and Post Exchange (PX) through his company Tradewell Co. By 1954 Tradewell was an established business selling beer, liquor, snacks, slot machines, jukeboxes, electrical appliances, building materials and vehicles to nonappropriated fund 8th Army activities.[1]: 874 After Whitney Crum graduated from the University of Southern California in 1954, he established a company called Tradewell Co. in Los Angeles which filled his brother’s orders for military clubs in South Korea.[1]: 875 Crum’s modus operandi involved providing lavish entertainment and gifts for local and U.S. civilian and military officials who could provide influence or protection. He would develop relations with club custodians and other procurement personnel and pay them kickbacks for awarding him contracts. He would also engage in smuggling or customs violations on imported items.[1]: 874 In 1958 Crum was banned from selling to Army clubs in South Korea following reports that he was giving kickbacks to Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) who served as NCO Club custodians, however the ban was lifted and Crum resumed business.[1]: 875 In 1960 further allegations of kickbacks were made, along with accusations that Crum was selling alcohol imported duty free into South Korea with his military club credentials into the South Korean domestic market. Both the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID) and South Korean customs authorities were about to take legal action against Crum when he left South Korea for Hong Kong on 13 October 1960.[1]: 875 operating from Hong Kong through the company Gande, Price Ltd (later renamed Price & Co.), Crum then set up operations at U.S. military facilities elsewhere in Southeast Asia as there was no effective information exchange between U.S. commands regarding his activities. He eventually expanded his business into South Vietnam as the U.S. military presence expanded there.[1]: 875, 880 The extent of Crum’s illicit activities in South Vietnam was made public in the United States Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations investigation into corruption in Army NCO clubs in Vietnam in 1971, known as the PX Scandal.

https://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,840224,00.html