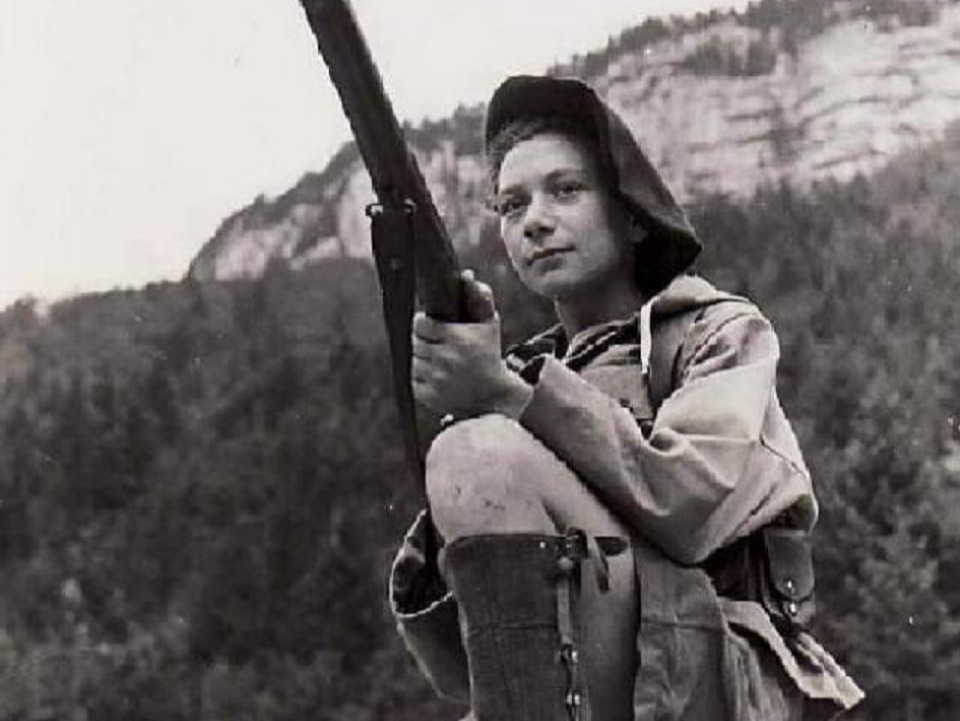

Nancy Wake with rifle in occupied France during World War II.

Nancy Grace Augusta Wake, also known as Madame Fiocca and Nancy Fiocca, was born on August 30, 1912, in Roseneath, Wellington, New Zealand. She was the youngest of six children. Her family moved to Australia when she was only two, where she attended school until she was 16.

Wake decided to run away to become a nurse. Rather than stay in Australia, she traveled to New York City, followed by London, where she went on to work as a journalist. It was while in this position that Wake watched the rise of the new German government in the 1930s. She was working in Paris, reporting on European news, and saw firsthand the way Jewish people, in particular, were being treated.

In 1939, Wake married Henri Edmond Fiocca and the two moved to Marseille, France. They were living there when the Germans invaded during the early stages of the Second World War. Wake served in uniform as an ambulance driver before France fell to the Germans. When it did, she continued to fight for her new home by joining the Pat O’Leary Line, one of the country’s many Resistance organizations. They evacuated Allied airmen who were shot down to Marseille, where Wake lived. From there, the pilots were shepherded to Spain, then Gibraltar and, finally, back to the United Kingdom.

Special Operations Executive (SOE)

The Special Operations Executive (SOE), was a secret British organization formed during World War II. It was officially established on July 22, 1940, under the supervision of Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare. The SOE was set up to wage a secret war. Its agents were mainly tasked with sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines. They had an influential supporter in Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who famously ordered them to “set Europe ablaze!”. The SOE was often referred to as the “Baker Street Irregulars” due to its headquarters being located on Baker Street in London, and the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare” for its unconventional and often ruthless methods of disrupting enemy operations.

SOE’s director of operations was Commando officer Brigadier Colin Gubbins whose interest in irregular warfare originated from his service during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21). Gubbins had also been involved in planning to establish a sabotage force to work behind the lines during any German invasion of Britain. He became head of the SOE in 1943.

The SOE operated in all territories occupied or attacked by the Axis forces, except where demarcation lines were agreed upon with Britain’s principal Allies, the United States and the Soviet Union. The organization directly employed or controlled more than 13,000 people, about 3,200 of whom were women. After the war, the organization was dissolved on January 15, 1946.

SOE Operative

When Nancy Wake arrived in England, she was accepted for SOE agent training. Reports from this time were very complimentary – even Vera Atkins, a high-ranking female agent, said Wake was “a real Australian bombshell”. After reaching Britain, Wake joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE) under the code name “Hélène”.

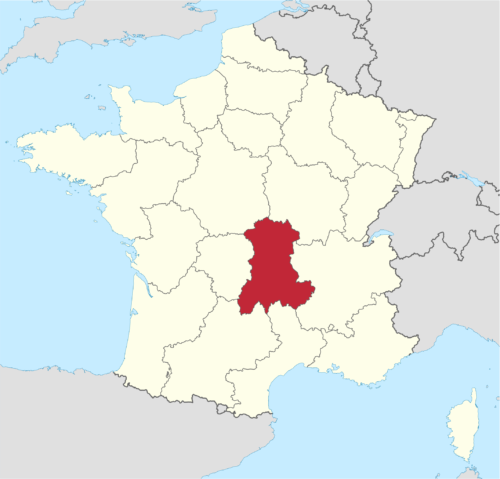

On April 29 to 30, 1944 as a member of a three-person SOE team code-named “Freelance”, Wake parachuted into the Allier department of occupied France to liaise between the SOE and several Maquis groups in the Auvergne region. This was a region in the heart of France, far from the relative safety of the coast. The mission was to liaise between the SOE and several Maquis groups in the Auvergne region. The Maquis were rural guerrilla bands of French Resistance fighters, called “maquisards”, during the Occupation of France in World War II.

Upon landing, her parachute got stuck in a tree. One of the Frenchmen greeting her said he hoped all trees could bear such beautiful fruit. To which she replied with her customary bluntness.

Wake’s role was pivotal in this operation. She served as a courier for the Freelance team, which had been sent as a liaison between London and the local French resistance group. Her high energy and clear ideas of how she wanted everything done were noted by Major John Farmer, the leader of the Freelance resistance circuit.

During her time with the Maquis, Wake participated in sabotage missions and direct engagements with the German forces. She was involved in several pitched battles with the Germans. In one instance, when the Germans launched an attack on another Maquis group, she took command of a section whose leader had been killed and with exceptional coolness directed the covering fire while the group withdrew with no further loss of life. After the battle, she claimed to have bicycled 500 kilometers to send a situation report to SOE in London.

This operation was just one of many that showcased Wake’s courage, resilience, and leadership skills. Her work significantly bolstered the morale and effectiveness of the French Resistance, contributing to the eventual liberation of France.

Wake was given the nickname “The White Mouse” by the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. This nickname was a testament to her ability to evade capture and slip through their grasp, much like a mouse. Despite a 5-million-franc price on her head, she managed to consistently outwit her pursuers, which led to her being one of the most wanted persons by the Gestapo. Her tactics often involved using her charm and wit to talk her way out of precarious situations.

At the end of the war, she learned that her husband, Henri Fiocca, had been tortured and killed by the Gestapo in 19433. After the war, she married RAF fighter pilot John Forward in 1957 and returned to Australia with him. However, she returned to England to live in 2001, four years after his death.

Her courage and resilience during the war earned her several awards, including the George Medal from the United Kingdom, the Medal of Freedom from the United States, the Légion d’honneur from France, a Companion of the Order of Australia from Australia, and the Badge in Gold from New Zealand.

Legacy

Wake’s life was marked by her courage, resilience, and dedication to the cause of freedom. Her work as an SOE operative during World War II was instrumental in the fight against the Axis powers, and her legacy continues to inspire people around the world today. Her only regret was not killing more enemy soldiers during the war. Nancy Wake passed away in Kingston upon Thames, London, England on August 7, 2011, at the age of 98.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.