Overview

Frank E. Petersen, First Black General in Marines, Dies at 83

Frank E. Petersen Jr., who suffered bruising racial indignities as a military enlistee in the 1950s and was even arrested at an officers’ club on suspicion of impersonating a lieutenant, but who endured to become the first black aviator and the first black general in the Marine Corps, died on Tuesday at his home in Stevensville, Md., near Annapolis. He was 83.

The cause was lung cancer, his wife, Alicia, said.

The son of a former sugar-cane plantation worker from St. Croix, the Virgin Islands, General Petersen grew up in Topeka, Kan., when schools were still segregated. He was told to retake a Navy entrance exam by a recruiter who suspected he had cheated the first time; steered to naval training as a mess steward because of his race; and ejected from a public bus while training in Florida for refusing to sit with the other black passengers in the back.

In 1950, only two years after President Harry S. Truman desegregated the armed forces, he enlisted in the Navy. The Marines had begun admitting blacks during World War II, but mostly as longshoremen, laborers and stewards. By 1951, he recalled, the Marine Corps had only three black officers.

But in 1952, Mr. Petersen, by then a Marine, was commissioned as a second lieutenant and the Marines’ first black aviator. He would go on to fly 350 combat missions during two tours, in Korea and Vietnam (he safely bailed out after his F-4 Phantom was shot down in 1968), and to become the first of his race in the corps to command a fighter squadron (the famous Black Knights), an air group and a major base.

Less confident men might not have persevered.

An instructor flunked him in training and predicted he would never fly. On his first day at the Marine Corps Air Station in El Toro, Calif., a captain claimed he was masquerading as a lieutenant and had him arrested. In Hawaii, a landlord refused to rent a house to him and his wife, and admitted to a subsequent prospect that he did so because they were black.

Racial discrimination was not all that General Petersen had to overcome.

He discovered while training that he was afflicted with acrophobia — fear of heights. And while he longed to be a general, he was happier wielding a joystick than working as a desk jockey.

After 38 years, he retired from the corps in 1988 as a three-star lieutenant general. He was the senior ranking aviator in the Marine Corps and the Navy, commander of the Combat Development Command in Quantico, Va., and special assistant to the chief of staff. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

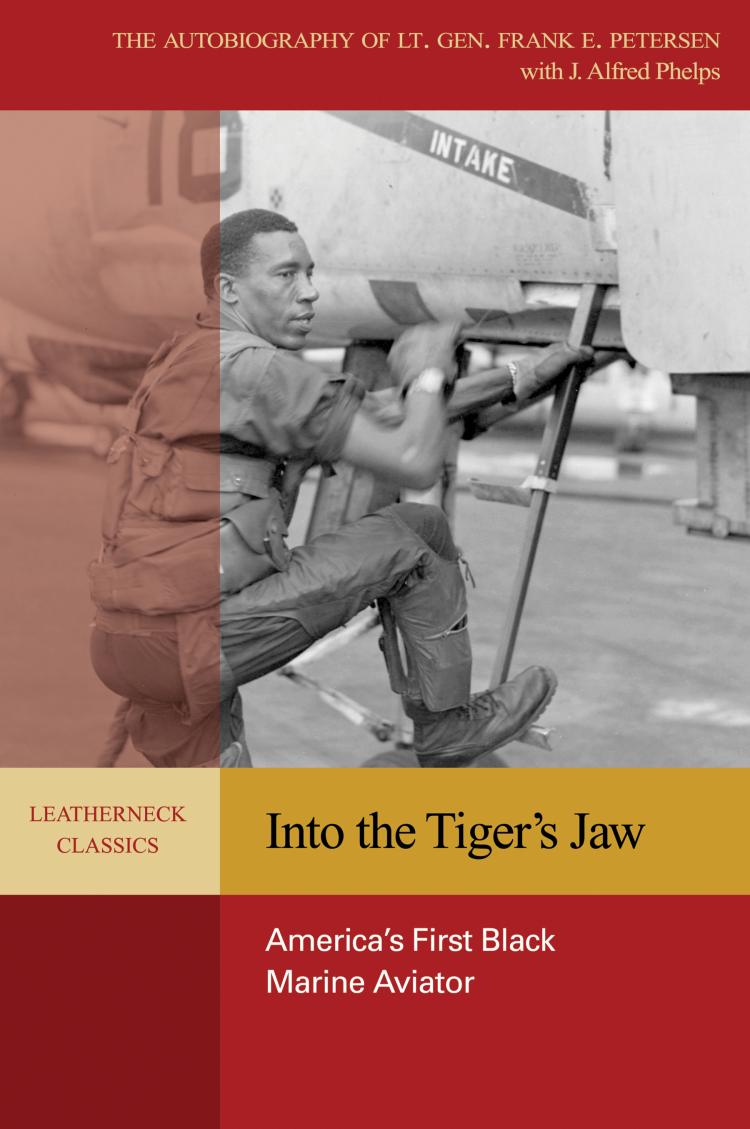

Much had changed in America since 1950, he recalled in his autobiography (written with J. Alfred Phelps), “Into the Tiger’s Jaw” (1998) — and the military, originally recalcitrant, had led the charge.

Promotions, job assignments and disproportionate punishments “were the three areas where racism was most likely to rear its ugly head for blacks then and, to some extent, still does today,” he wrote.

Appointed a special assistant to the commandant for minority affairs in 1969, he recalled, he sought to eradicate barriers among recruits from different backgrounds, with palpable improvement.

“The signs of it are subtle,” he wrote. “As you go off a base, look around. If you see a white kid and a black kid going off together to drink a beer, you know that you’ve achieved a degree of success.”

Obviously there has been progress, he said, and the military has been a model for integration.

Had there been enough progress?

“Never.”

Frank Emmanuel Petersen Jr. was born in Topeka on March 2, 1932. His father, who was born in the American Virgin Islands, was a radio repairman and a General Electric salesman. His mother, the former Edythe Southard, was a teacher.

Young Frank experienced the world beyond Kansas largely through radio, and his perspective was frequently refracted through race.

Naturally, the family rooted for Joe Louis, he said, because “where else but in the ring could a black man kick a white man’s ass with impunity and walk away smiling with a pocket full of money?”

He was 9 when Pearl Harbor was attacked on Dec. 7, 1941, and while he was unsure what war was, he knew the Japanese had done America wrong. “I was scared,” he recalled, “but happy that it hadn’t been black people who’d done it.”

He enrolled in Washburn University in Topeka, but when he turned 18 and no longer needed his parents’ permission (his mother had opposed him joining the military), he enlisted in the Navy.

He began as a seaman apprentice and electronics technician and in 1951 entered the Naval Aviation Cadet Program.

He graduated in 1967 from George Washington University and later received his master’s degree, both while in the Marines.

General Petersen’s marriage to the former Eleanor Burton ended in divorce. Survivors include their children, Gayle, Dana, Lindsey and Frank III; his second wife, the former Alicia Downes, and their daughter, Monique; a grandson; and three great-grandchildren.

After leaving the military, General Petersen became a vice president for corporate aviation at Dupont de Nemours. He retired in 1997.

In a video interview for the National Visionary Leadership Project, he reflected on becoming the first black Marine Corps general and the only one for nearly a decade until he retired.

“Just to be able to say you kicked down another door was such a great satisfaction,” he said, but it was also a challenge. “Whereas you thought you could perform before, now you must perform.”