Brian Lavery’s book is something that I truly enjoyed reading. I have gazed at the ship models on its pages over and over again since receiving it last month from the U.S. Naval Institute Press Mr. Lavery’s book is titled Wooden Warship Construction a History in Ship Models. He traces the evolution of naval sailing vessels using models accompanied with historical tidbits that range from present day models and also go as far back as the mid-seventeenth-century. All of the models shown in the book come from the UK National Maritime Museum and their collection is one of the largest collections of scale ship models in the world. I knew precious little about ship building and ship modelling prior to reading this book. I truly came away from it with a huge appreciation for shipwrights and historians of naval ships. I can see why there are fans of ships and of ship models.

Naval ships were usually called warships or combatant ships and they were primarily intended for naval warfare. Unlike merchant ships warships are designed to withstand damage and they will be faster and more maneuverable. They typically carry only weapons, ammunition and supplies instead of cargo like merchant ships do. It is notable that wooden warships were made obsolete with the construction of the first ironclad warships named the French Gloire and British Warrior. Wood was soon replaced by metal as the main material in the construction of warships.

The author spent a lot of his time at the UK National Maritime Museum and his intimate knowledge of shipbuilding shows. Lavery, is a British naval historian, author, and Curator Emeritus at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, England according to his biography posted online.

According to the bio, “In 2007 he was presented with the Desmond Wettern Maritime Media Award for contributing ‘to our understanding of the social structure of Britain’s maritime power and all maritime aspects of British national life’. In the following year he won the Anderson Medal of the Society for Nautical Research.

During 14 years in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich he developed the modern collecting policy and worked on numerous exhibitions such as Seapower, All Hands, and several of the galleries in the Neptune Court development. He has lectured regularly on cruise ships, including many trips on the square rigger Sea Cloud, and he undertakes maritime tours in the United Kingdom and Europe. Traditional Boats & Tall Ships refers to him as “one of the world’s leading naval historians.” He has since published over 30 books, covering marine architecture, ship construction (including several in Conway’s Anatomy of the Ship series), and naval warfare from its infancy to present day. He is a leading expert in the career of Nelson and the broader Royal Navy. Patrick O’Brian found Nelson’s Navy (1989) to be “the most nearly regal that I have come across in many years of reading on the subject.” The Times labelled the same book a “masterpiece on life in the Senior Service under England’s favorite seafaring son.”

This book includes plentiful visual representations of actual ships in model form and the accompanying graphics make for wonderful reading. Even if you do not read a single word in the book the models alone create enough gog in a person of any age. The models were all built to scale and the attention to detail is mesmerizing.

A movie with such a big budget and stars such as Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany needs to be as historically accurate as possible. Peter Weir‘s 2003 blockbuster film Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World used the services of Lavery as a historical consultant. I thoroughly enjoyed watching the ship battles and the movie sets being put to use. Warships began to carry an increasing number of cannons on their broadsides by the middle of the 17th century. In order to bring each ships’ firepower to bear in a line of battle tactics had to evolve.

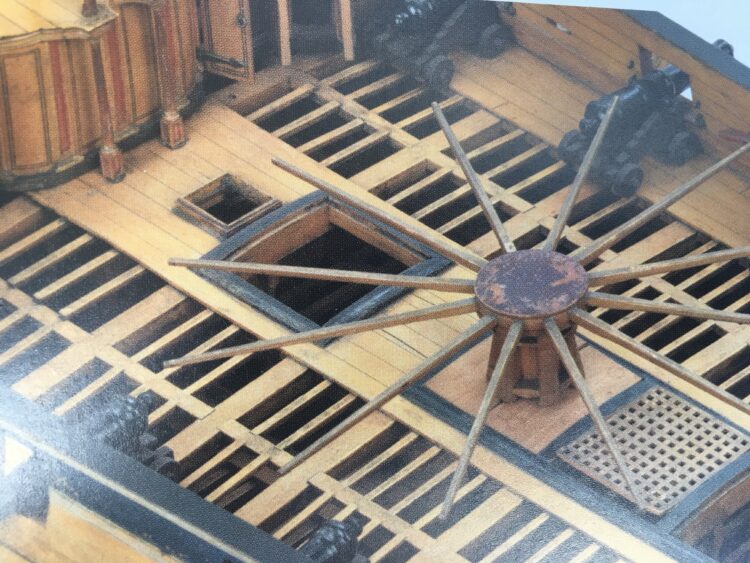

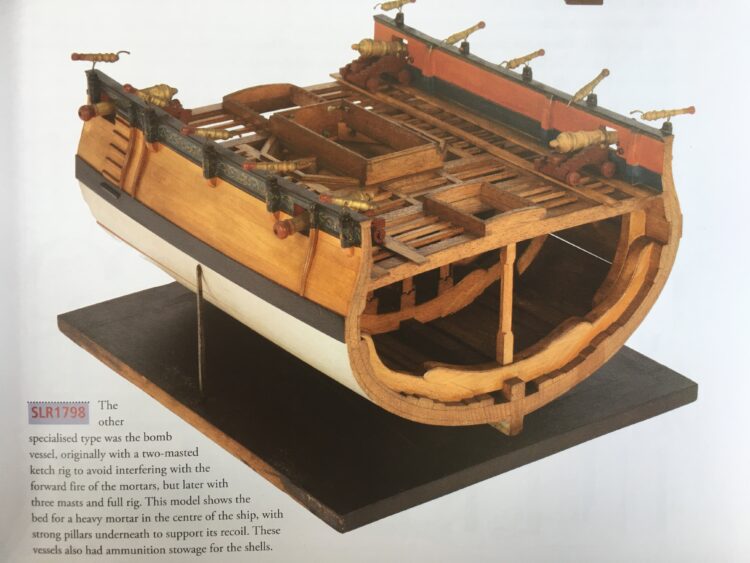

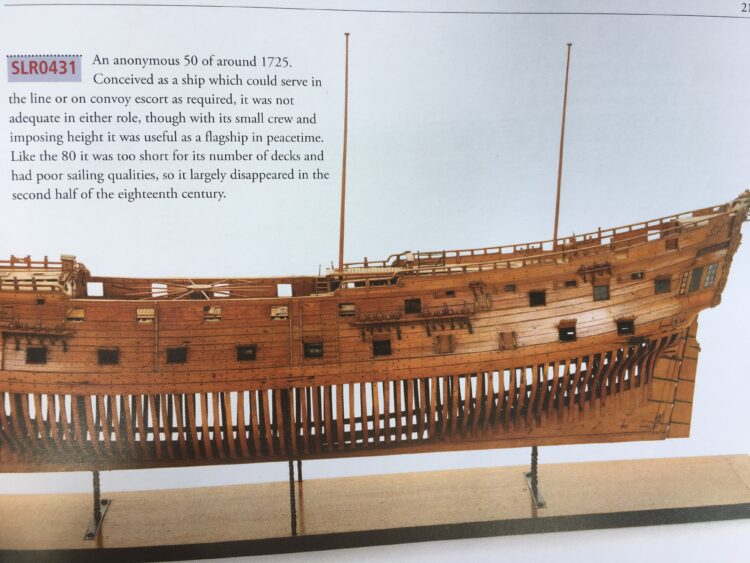

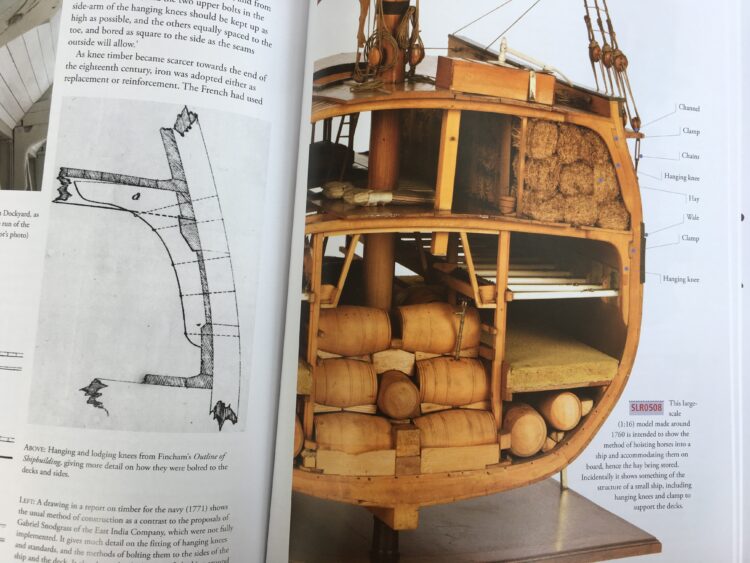

For those like myself who know precious little about the layouts of sailing vessels Lavery pulls together information from various sources to make a very enjoyable and digestible book on model ships. His book is broken down into seven chapters: Labour and Materials, Starting the Ship, Frames, Outside Planking, Inside the Hull, Fittings and In the Water. Each of those chapters includes very clear photographs of specific ship models, a robust description of ship construction techniques and interesting illustrations and historical manuscripts. All of these elements together creates an interesting story for the reader to follow, from start to finish, so the reader can understand more than just the construction techniques used to build a ship. The reader is educated on the costs of building a ship, how locations are scouted for building a ship, and the lumber used among many subjects covered over 128 pages. The pages are crisp, the illustrations and photos are clear, and I cannot express enough how enjoyable this book is to read.

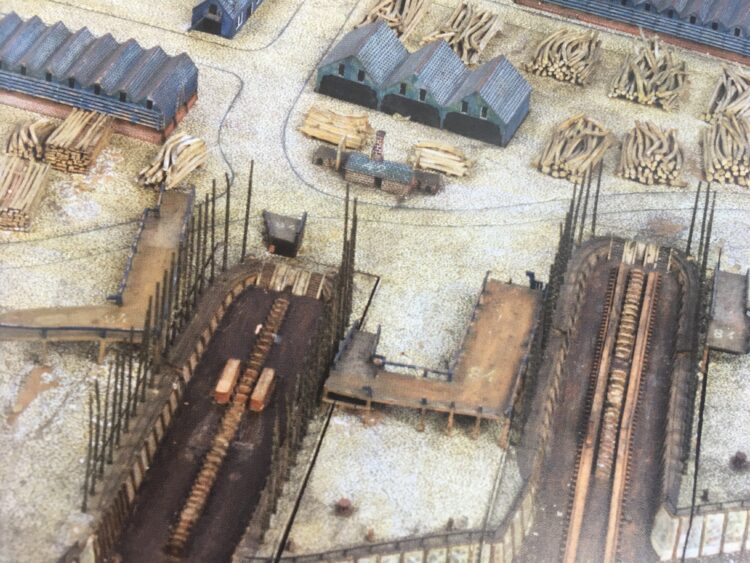

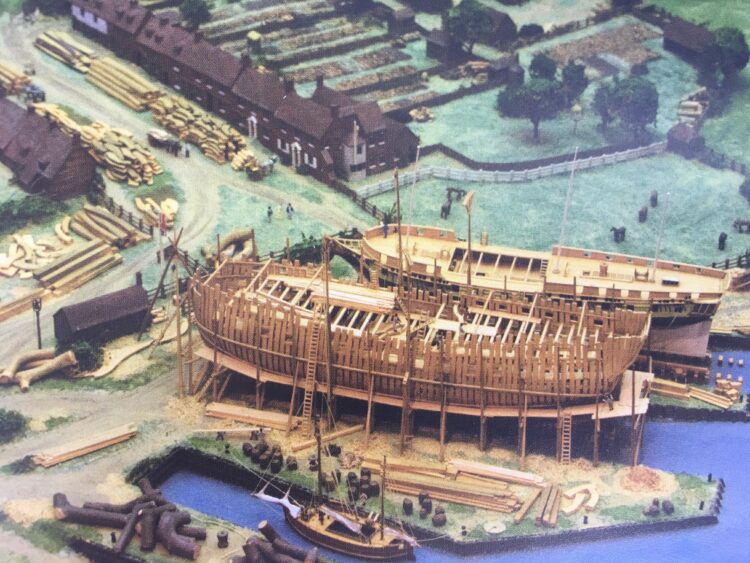

Lavery offers lots of bits of interesting facts about shipbuilding. For example, he wrote, “Shipyards were relatively simple in the 18th and 19th century and needed little capital equipment. The main requirement was a site on a firm bank close to the river which was deep enough for launching the ship.”

The sections on British dockyards, shipwrights, and the tools used are interesting. Whole communities of people were built around the dockyards. There is a section written of on the different parts of trees used and how timber is stored that really piqued my interest. British Oak was preferred for ship building so not just any kind of timber would do. Each piece had to be large enough to be useful. Timber merchants provide most of the materials. It was noted that fir timber coming from North America in general did not have the strength of the Baltic fir, and oak from the southern provinces ‘is not fit for the navy.’ These little fascinating insights made my Sunday coffee and book reading afternoons very enjoyable.

At one time in England their Royal Dockyards employed more than 15,000 men and they were not devoted to building ships but rather for maintenance. Various types of ships, from 20 gun ships to 74 gun ship and even more, are written about and a reader can see the sizes compared and contrasted on the pages. The longest wooden ships in known history measured from 59-56 meters (193 to 184 feet) to over 100 meters (328 feet). The Appendix covers the proposed cost of the shipwrights’ work in building several vessels and for repair and it lists ships with 100, 74, 44, or 32 guns.

By the 1790s construction methods allowed for the windows of the wardrooms and the galleries and captain’s cabins to be lighter. Ships fought rigidly in the line of battle and their sterns were rarely exposed to gun battle. Nelson and others began to change tactics and one was to rake the enemy by getting across their stern and firing through the weak structures.

Lastly, one of the coolest bits of information given is that some of the ship images have a catalog number written on them. Simply by going to the museum’s website and entering the corresponding number marked on the photo will take you to that particular ship web-page where you can find much more about the ship and model in the maritime museum’s extensive collection. Here is the collections website. Again, just enter the corresponding reference number in the search box.

If you get a chance, pick up one of these books, either for yourself or for a friend. I believe you will enjoy it.

Material Disclosure

I received this product as a courtesy from the manufacturer via Spotter Up so I could test it and give my honest feedback. I am not bound by any written, verbal, or implied contract to give this product a good review. All opinions are my own and are based off my personal experience with the product.

*The views and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of Spotter Up Magazine, the administrative staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.