When President John F. Kennedy established the Navy SEALs in 1962, he envisioned a force capable of unconventional warfare, small, highly trained units that could operate in jungles, rivers, and coastal waters where traditional forces struggled. Vietnam became their proving ground.

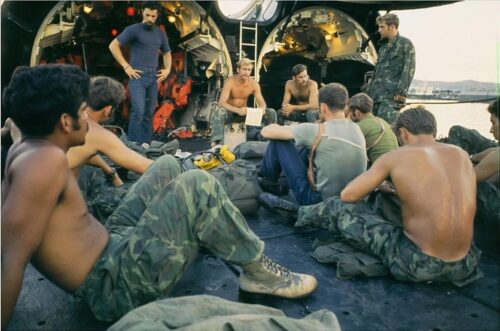

The SEALs quickly earned a reputation as “the men with green faces,” a nickname given by the Viet Cong for their camouflage paint and stealth tactics. They conducted reconnaissance, ambushes, and direct-action missions in the Mekong Delta, often working in small teams of four to six men. Their operations were dangerous and intimate, close-quarter firefights in swamps, villages, and rivers where escape routes were few. By the late 1960s, SEALs had become one of the most feared and respected units in the war.

Operation Thunderhead

By 1972, U.S. combat operations were winding down, but the plight of American prisoners of war remained urgent. Many of these men were confined in the notorious Hỏa Lò Prison in Hanoi, grimly nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton” by its captives.

Conditions inside were harsh. Prisoners endured isolation, beatings, and deprivation. Yet the will to escape never fully disappeared. Among the most determined was Air Force Colonel John A. Dramesi.

In 1969, Dramesi and fellow POW Captain Edwin Elias attempted a daring breakout from the “Zoo” camp (Cu Loc Prison) in Hanoi. They were captured after only a few hours, and the punishment was brutal: both men were beaten and tortured, and the entire POW population suffered harsher conditions afterward.

Undeterred, intelligence later suggested that Dramesi and Elias were again considering escape—this time from Hỏa Lò itself. Their plan was to slip out, steal a boat, and follow the Red River to the Gulf of Tonkin, where they hoped U.S. forces could rescue them. Although this second attempt never materialized, the possibility was taken seriously by U.S. planners and directly influenced the launch of Operation Thunderhead in 1972.

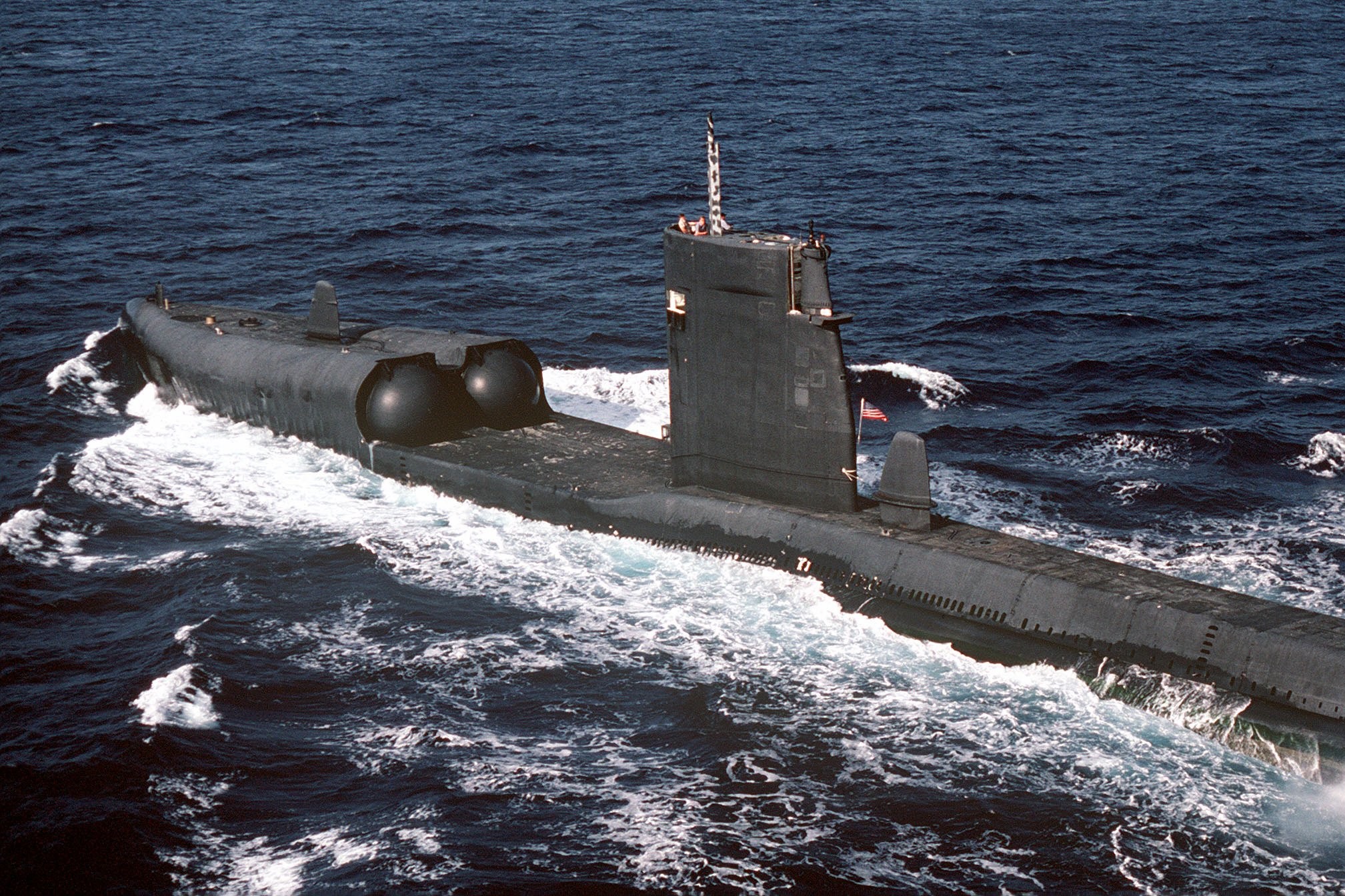

To support this daring plan, the Navy launched Operation Thunderhead, a highly classified mission involving SEAL Team One and Underwater Demolition Team 11 (UDT-11). The submarine USS Grayback, modified to carry SEALs and their Swimmer Delivery Vehicles (SDVs), was chosen as the launch platform.

The USS Grayback had an unusual history. Originally commissioned in 1958 as SSG-574, a guided missile submarine designed to carry Regulus cruise missiles, she was later converted in 1969–1970 into a transport submarine for special operations. After this transformation, she was redesignated LPSS-574 (Landing Platform, Submarine). By the early 1970s, Grayback had become one of the Navy’s most secretive assets, outfitted to deploy SEALs, UDT teams, and SDVs directly from her hull. This conversion made her a critical tool for clandestine missions like Thunderhead, where stealth and the ability to insert small teams close to enemy shores were essential. Grayback’s role in the operation reflected the growing importance of submarines in special warfare, a precursor to the modern use of subs as covert platforms for SEAL delivery.

The Mission Unfolds

The plan was audacious. SEALs from Team One, supported by Underwater Demolition Team 11, would deploy covertly from the submarine USS Grayback, using Swimmer Delivery Vehicles (SDVs) to reach the North Vietnamese coast undetected. Once ashore, they were to rendezvous with escaping POWs and guide them to safety.

From the outset, however, the mission was plagued by difficulties. Intelligence was fragmentary, the seas were rough, and the SDVs suffered repeated mechanical problems. Communication with the prisoners never materialized, leaving the SEALs to press on in uncertainty, fully aware that capture meant torture or execution.

On the night of June 6, 1972, tragedy struck. As part of the operation, a SEAL element attempted a hazardous parachute insertion from a helicopter into the Gulf of Tonkin. In the heavy seas and strong currents, Lieutenant Melvin Spence Dry, leading the team, was separated and drowned before he could be recovered. Despite desperate rescue efforts, he was lost. His death marked the final combat loss of a Navy SEAL in Vietnam, closing a chapter of sacrifice and valor in one of the war’s most secretive missions.

Secrecy, Aftermath, and Legacy

For decades, the details of Operation Thunderhead remained hidden from public view. Classified at the highest levels, the mission was known only to those who had taken part and a handful of planners in Washington. The details were hidden even from families. Dry’s father, retired Navy Captain Melvin H. Dry, spent years seeking answers about his son’s death.

It was not until the early 2000s that the operation was formally declassified, and its story began to emerge. Accounts from surviving SEALs and UDT members, combined with official Navy records, revealed the extraordinary risks they had undertaken in hopes of rescuing fellow Americans. The disclosure also confirmed the tragic loss of Lieutenant Melviin Spence Dry. In recognition of his bravery and sacrifice, Lieutenant Melvin Spence Dry was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal.

Though the mission failed to rescue POWs, it symbolized the SEALs’ ethos: no man left behind, no mission too dangerous. It was a final act of courage in a war that had tested the limits of America’s special operations forces.

The Vietnam War transformed the SEALs from experimental units into a permanent fixture of U.S. military power. Their experiences in the Mekong Delta, coastal raids, and missions like Thunderhead forged the tactics and traditions that define Naval Special Warfare today.

Final Thoughts

Operation Thunderhead was a daring, desperate mission that reflected both the ingenuity and the risks of special operations in Vietnam. Lieutenant Melvin Spence Dry’s sacrifice remains a poignant reminder of the cost borne by SEALs in their commitment to rescuing comrades. His death marked the end of SEAL combat losses in Vietnam, but the lessons of the war ensured that the SEALs would emerge stronger, shaping their legendary role in conflicts to come. It also stands as a testament to the secrecy of Cold War-era special operations, missions carried out in silence, their sacrifices acknowledged only decades later.