[jetpack_subscription_form]

Randall Jarrell (May 6, 1914 – October 14, 1965) was an American poet, literary critic, children’s author, essayist, novelist, and the 11th Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a position that now bears the title Poet Laureate.

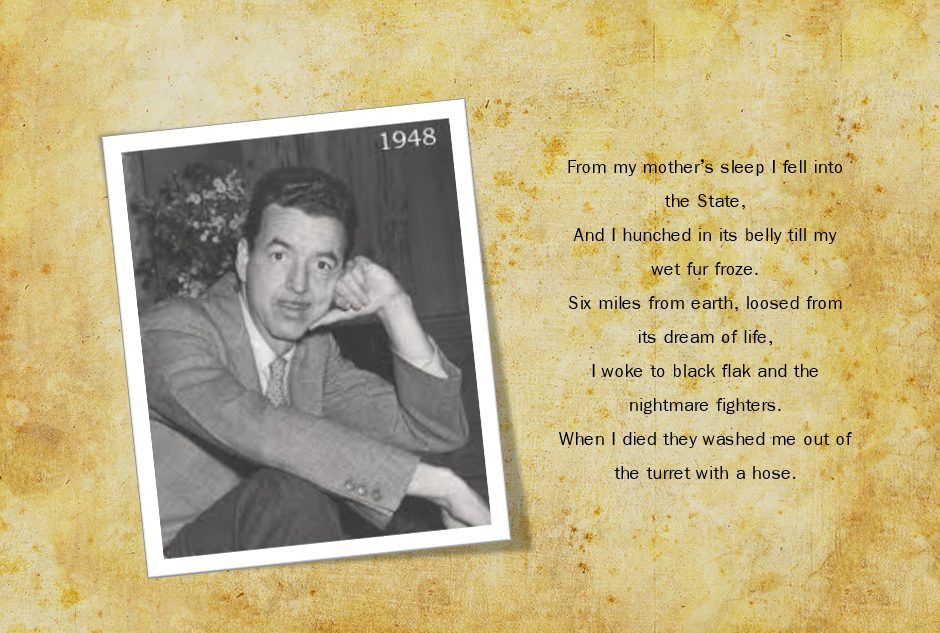

The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner is Jarrell’s best known poem. It is a brief poem, five lines in total. He published it in 1945. Most Flying Fortress crew members considered the Sperry ball turret the worst crew position on the aircraft. Beneath the aircraft the gunner was seated in a fetal position, confined to a solitary place, in order to defend the plane. His turret revolved in 360 degrees. The gunner was given a panoramic view of the world below him.

Jarrell, who served in the Army Air Forces, provided the following explanatory note:

A ball turret was a Plexiglas sphere set into the belly of a B-17 or B-24, and inhabited by two .50 caliber machine guns and one man, a short small man. When this gunner tracked with his machine guns a fighter attacking his bomber from below, he revolved with the turret; hunched upside-down in his little sphere, he looked like the fetus in the womb. The fighters which attacked him were armed with cannon firing explosive shells. The hose was a steam hose.

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

Jarrell entered the Army Air Force in 1942. He attempted to become a flyer but failed to qualify. Instead, he became a celestial training navigator and ended up in Tucson, Arizona. Jarrell wrote many poems during his time in the service. From 1942-1946 he spent those four years writing many poems about the war and his time in the army. His two books titled, Little Friend, Little Friend (1945) and Losses (1948), were created using the material he had accumulated.

Upon his separation from the military Jarrell became the literary editor for the Nation. During his time at the Nation he collected poems and made reviews of other poets, many of these were some of the best from England and America. Jarrell would have a very successful career but tragedy would strike his family. In 1964 he was struck by a car and died. The poet Robert Lowell wrote, “There’s a small chance [that Jarrell’s death] was an accident. . . [but] I think it was suicide, and so does everyone else, who knew him well.”His wife stated that Jarrell would never do such a thing. Whatever the truth, Jarrell died on Oct 14th, 1964 but his poetry still lives on. His obituary is below:

The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

Mail Call

The letters always just evade the hand

One skates like a stone into a beam, falls like a bird.

Surely the past from which the letters rise

Is waiting in the future, past the graves?

The soldiers are all haunted by their lives.

Their claims upon their kind are paid in paper

That established a presence, like a smell.

In letters and in dreams they see the world.

They are waiting: and the years contract

To an empty hand, to one unuttered sound —

The soldier simply wishes for his name.

— from “Little Friend, Little Friend.”

November 25, 1945

Gunner

Did they send me away from my cat and my wife

To a doctor who poked me and counted my teeth,

To a line on a plain, to a stove in a tent?

Did I nod in the flies of the schools?

And the fighters rolled into the tracer like rabbits,

The blood froze over my splints like a scab —

Did I snore, all still and grey in the turret,

Till the palms rose out of the sea with my death?

And the world ends here, in the sand of a grave,

All my wars over? How easy it was to die!

Has my wife a pension of so many mice?

Did the medals go home to my cat?

— from “Little Friend, Little Friend”

October 13, 1946

A Front

Fog over the base: the beams ranging

From the five towers pull home from the night

The crews cold in fur, the bombers banging

Like lost trucks down the levels of the ice.

A glow drifts in like mist (how many tons of it?),

Bounces to a roll, turns suddenly to steel

And tyres and turrets, huge in the trembling light.

The next is high, and pulls up with a wail,

Comes round again – no use. And no use for the rest

In drifting circles out along the range;

Holding no longer, changed to a kinder course,

The flights drone southward through the steady rain.

The base is closed…But one voice keeps on calling,

The lowering pattern of the engines grows;

The roar gropes downward in its shaky orbit

For the lives the season quenches. Here below

They beg, order, are not heard; and hear the darker

Voice rising: Can’t you hear me? Over. Over –

All the air quivers, and the east sky glows.

Losses

It was not dying: everybody died.

It was not dying: we had died before

In the routine crashes– and our fields

Called up the papers, wrote home to our folks,

And the rates rose, all because of us.

We died on the wrong page of the almanac,

Scattered on mountains fifty miles away;

Diving on haystacks, fighting with a friend,

We blazed up on the lines we never saw.

We died like aunts or pets or foreigners.

(When we left high school nothing else had died

For us to figure we had died like.)

In our new planes, with our new crews, we bombed

The ranges by the desert or the shore,

Fired at towed targets, waited for our scores–

And turned into replacements and woke up

One morning, over England, operational.

It wasn’t different: but if we died

It was not an accident but a mistake

(But an easy one for anyone to make.)

We read our mail and counted up our missions–

In bombers named for girls, we burned

The cities we had learned about in school–

Till our lives wore out; our bodies lay among

The people we had killed and never seen.

When we lasted long enough they gave us medals;

When we died they said, ‘Our casualties were low.’

They said, ‘Here are the maps’; we burned the cities.

It was not dying –no, not ever dying;

But the night I died I dreamed that I was dead,

And the cities said to me: ‘Why are you dying?

We are satisfied, if you are; but why did I die?’

Randall Jarrell, Poet, Killed by Car in Carolina

SPECIAL TO THE NEW YORK TIMES

Mr. Jarrell, 51 years old, a member of the English faculty at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, was struck by an automobile as he walked along the heavily traveled Chapel Hill bypass, U.S. 15-501. There was no immediate explanation for Mr. Jarrell’s presence as a pedestrian on the highway.

State Trooper Guy C. Gentry, Jr. said, “We are going on the assumption that it was suicide.” He said witnesses reported that the victim had “lunged into the side of the car that struck him.” No charges were placed against the driver.

The body was identified by friends of the poet on the campus at Chapel Hill.

“It has been clear for some time,” wrote a critic in The New York Times Book Review, “that Randall Jarrell is one of the most gifted poets and critics of his generation.” That was in 1953.

Four years later Mr. Jarrell made this observation about a poet’s place in society: “The public has an unusual relationship to the poet, it doesn’t even know that he is there.”

But the literary community knew that the bearded Mr. Jarrell was around. His criticisms appeared frequently, his books were published often and his name appeared with some regularity among the winners of writing awards.

He was appointed in 1956 to a two-year term as Consultant in Poetry in English at the Library in Congress.

He was at various times literary editor of The Nation and poetry critic for both the Partisan Review and the Yale Review.

Mr. Jarrell received the National Book Award for poetry in 1960.

Considered one of the “younger poets,” he commented in 1957 that “most modern poetry isn’t modern any more.”

“The new poets scan,” he went on. “They have rhyme and rhythm. The idea that they are wild and woolly is no longer true. Today the young poets are tame and fleecy.”

Mr. Jarrell was born in Nashville, Tenn., on May 6, 1914. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1935 from Vanderbilt University and did graduate work there, getting a master’s degree in 1938. He taught at the University of Texas from 1939 to 1942, when he entered the Army Air Force.

Starting as a flying cadet, he later became a celestial navigation tower operator, a job title he considered the most poetic in the Air Force.

After being discharged from the service he joined the faculty of Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, N.Y., for a year before going to the Woman’s college of the University of North Carolina where, as an associate professor of English, he taught modern poetry and imaginative writing.

He participated in the Salzburg Seminar in American Civilization in 1948, lectured in the Princeton Seminars in Literary Criticisms in 1951-52 and taught for a while at the University of Illinois.

Mr. Jarrell received Guggenheim Fellowship for 1947-48 and a grand from the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1951.

His works appeared in the Sewanee Review, Kenyon Review, Partisan Review, Poetry, the Nation, The New York Times Book Review and other publications.

He received the National Book Award for a collection of poems entitled “The Woman at the Washington Zoo,” published by Atheneum, which explored the world of loneliness and near despair through the eyes of a woman.

Safe from all the nightmares

One comes awake in the world, she sleeps.

She sleeps in sunlight, surrounded by many dreams

Or dream of dreams, all good — how can a dream be had

If it keeps one asleep?

A critic once wrote of him, “Jarrell moves forward to what may very well be the beginning of a new evaluation of poetry, what it is and what it can be.”

Mr. Jarrell said most people did not understand poets or poetry, but he added, “Take Johnny Unitas, quarterback on the Baltimore Colts. Only a few people up in the stands understand what he is doing. Most of them have seen only a few games and they couldn’t hope to understand what is going on.”

His last collection of poems, “Lost World,” was published last summer.

His other books included “Blood of a Stranger” (1942), “Little Friend, Little Friend” (1945), “Losses” (1948), “The Seven-League Crutches” (1951), “Poetry and the Age” (1953), “Pictures From an Institution” (1954), “Selected Poems” (1955), “The Anchor Book of Stories” (1958) and “A Sad Heart at the Supermarket” (1962).

He also wrote “The Gingerbread Rabbit,” a children’s book, and “The Bat-Poet.” He was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

The poet was married in 1952 to Mary von Schrader.

pic from englishwithmccabe.blogspot.com

[jetpack_subscription_form]